Rococo redux

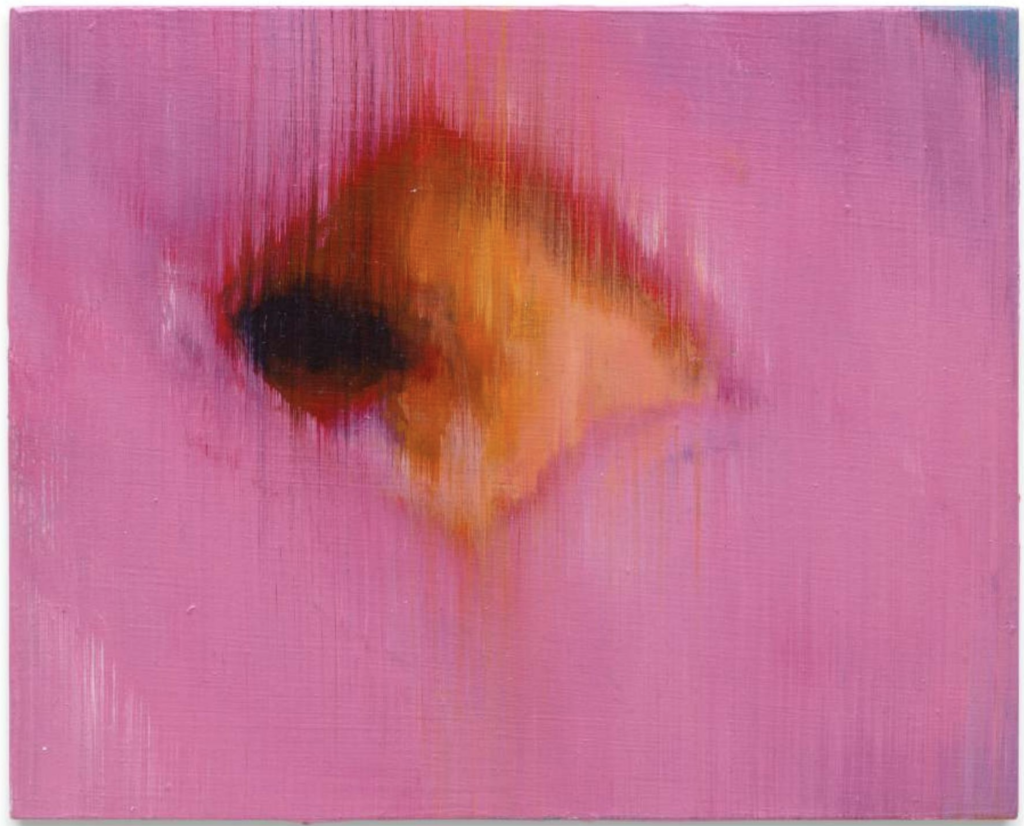

Purity, oil on panel, 5 1/4 x 6 5/8.

The Rococo era, with its beautiful, frilly tribute to eroticism and abundance, flourished for a few decades in the 18th century before the French Revolution brought it to a violent halt. The Jacobins used a guillotine on all the privileged fun one sees in paintings from the mid 18th century. Chardin, the greatest of the French painters in that century, belonged to this era, but mostly he lived in it while not really being of it. Watteau, Fragonard, Boucher, and Tiepolo embodied the effervescence of rococo painting while depicting what must look to most people in our era (so glumly serious about politics) like scenes of fatuous and frivolous pursuits. Tiepolo, though, had a conscience. A painting I saw for the second time late last year at the Norton Simon in Pasadena is the marvelously simplified Allegory of Virtue and Nobility: it’s about the conscious choice to be good. And rococo is far from irrelevant in any era: one thing is self-evident to anyone who has seen The Progress of Love at The Frick: Fragonard was a preternaturally talented painter who knew exactly how women win the hearts of men. The immense imbalances of wealth that led up to the revolution sustained his creativity and nourished the work of many others. Fragonard’s productive years ended with the Reign of Terror. Great wealth feeds great art. Until it doesn’t.

Actually, Chardin’s bubble-blower might fit nicely here as an emblem of a much larger bubble that burst when all of this disappeared into the chaos of the new France. It seems we’ve lived in the era of his bubble-blower for decades now: the dot.com bubble, the real estate bubble, smaller ones bursting within the overarching long-term bull market that has been fueled in many ways by dizzying levels of unsustainable debt. (We have been in the Lord Voldemort of bubbles for decades, the one whose name we don’t speak.) The wealthy are getting wealthier every year, in some cases faster than at any time in history out of financial maneuvers rather than creative contributions from genuine labor in and devoted to the actual world. It all feels a bit rickety.

So it’s little wonder that visual art in many ways now echoes the Rococo era: the decorative energy, its flamboyant excesses and its lush eroticism with a fervor that implies it can’t last. (Let’s get our kicks now while there’s time!) What this means for the future, who knows, but for now it can be a delight because in many cases its generating art that’s meant to be loved for the desire and pleasure it embodies. It isn’t ameliorative or scolding or therapeutic, as Dave Hickey might have put it. It’s art made with a life-affirming energy. The music of Phoenix, a band I never tire of listening to—French of course—should be the soundtrack for all this.

Lisa Yuskavage, Will St. John, even Kehinde Wiley and Zoey Frank with the decorative patterning that plays a key role in so much of Wiley’s and Frank’s work, are all indebted to different elements of rococo. Flora Yukhnovich reimagines rococo scenes as gestural, painterly impressions somewhat the way Elise Ansel does with other paintings from various eras. Daniel Bilodeau’s floral still lifes at Arcadia Contemporary and at the LA Art Show last month are another outstanding example. You can find elements of rococo now everywhere.

Emily Eveleth’s new show at Miles McEnery shows that she has enlisted her skills into this neighborhood of visual exuberance. She has stayed mostly true to the self-imposed limits of her chosen subject: glazed donuts, jelly donuts, sugared donuts. It’s the gamut of donuts, which isn’t much of a gamut unless, say, you enlist apple fritters or crullers or eclairs into the mix. I’m only half kidding. Where does one go? The new show demonstrates where it has led.

Her allegiance to donuts is a discipline. It’s like Rothko’s unwillingness to try anything outside that heaven-earth-horizon format that became his only way of expressing various human states of being. For years, I thought Eveleth had backed herself into a corner. The original glazed donuts, seen with the viewer’s eyes at the level of the surface (the way William Bailey always lined up his assiduously un-shiny antique pottery on a shelf or table) were wonderfully humble, but also baroque in their spotlit elegance. The light settled on the sugary glaze from above and seemed to caress the muted browns and golds in the front rim of the pastry, everything at rest—it felt like a cross between Rembrandt and a Chardin brioche, with a dignity that nothing other than the light and the dark backdrop provided, along with the restraint of her paint handling. She moved from those original, classic still lifes to jelly donuts slouched against a vertical surface and oozing their innards in a way that felt anatomical and seemed decadent and suggestive in comparison with the earlier images where all the expressive possibilities were restrained and channeled through the sensuous accuracy of her brush. That was when I wondered, how does she get out of this? What’s the next step? Accuracy restrained her color choices and compositional options. How would you move on except by doing a huge pivot into some other format, another kind of subject?

She stuck with donuts. It’s what anyone could learn from the fundamental abstractionists: Rothko, De Kooning, Stella (in the Sixties), Albers, Agnes Martin. Find a format and keep dancing with the one you brought. See if you could learn to move in new ways without changing partners. In the past decades, she has found greater freedom in the corner she constructed for herself to get started. Staying in place, she’s turned around and faced the other way. She has gotten even looser with her paint and more arbitrary with her color. Her earlier show in 2021 and this current exhibit demonstrate that she’s evolving more toward a focus on color and improvisation, and she’s moving closer to gestural abstraction. She hasn’t pulled up her anchor in the representational core of her image, but it’s dragging along the bottom a bit. The results are impressive, though a little mixed here and there.

Some of her tropes are fantastic: wallpaper patterns that look as if they were stenciled through thin, filigreed metal onto another sheet of metal. Flagrant juxtapositions of flat patterns juxtaposed against lush thick renderings of donuts like big velour bean bags. Her feeling for color harmonies can be wonderful. When she cuts loose, she’s earned the right to have her way with donuts and it’s fun to see what she can think up. The pink flamingos as wallpaper behind one figure seem a bit of a joke: see what I can get away with! Yet the work is always exhilarating because there’s not a snide or sorry note in anything she’s doing, and those oozing wounds in the jelly donuts are universal, aren’t they? Everything dissolves and comes apart eventually. In her most powerful paintings she stays true to the earlier spirit of closing most of her options, the restraint that Hemingway described as the iceberg. What’s underwater remains inherent in the work, withheld and pushing for expression but held back, giving power to what little is visible.

The Small Rooms of Paris: radiant golden jelly donuts sitting one on top of another, with their little sweet ports puckered and singing some silent praise for being in Paris, against a very subtle, complementary wallpaper of turquoise and Thalo blue. The Soft Machine: two pale donuts stacked so that the mouth of the top one shows just a little red, a small hot tone crowning an orange-pink cairn of flour and fat. The simplicity of the entire composition harks back to her earliest work and the seminal American abstractionists. Diary of a Thief owes plenty to Matisse with its decorative background and reflections in the surface under the donut, though that blatant, blood-red orifice brings the viewer up short in a way Matisse never did. A tiny miniature, Purity, is a marvel of simplicity and restraint. It’s a detail painting of a center hole in a glazed donut where the paint uniformly trails down from the upper edge as if scraped—Richter style—in a way that creates an abstract image that is still amazingly representational. She has used that technique for years, giving her paint those downward ridges, like uniform brush marks offering a febrile sense of potential motion as if the whole painting were paused digital image on a screen. The most interesting painting in the entire show, Flesh and Blood, owes a slight debt to the earliest Alyssa Monks paintings of women seen through wet glass. Eveleth has worked from a shot of a donut glimpsed through a glass fogged with mist like a bathroom mirror. She drew what appears to be a lion’s silhouette with her finger, wiping clarity into the frost on the glass as the excess water drips away at the bottom. You see a portion of the donut clearly through that shape with the rest dissolving into a haze of mist. What’s powerful is how much remains inaccessible and merely suggested here, everything you glimpse obscurely through the fog, with all the most intense color visible in a small area of the canvas, the tip of the iceberg.

Comments are currently closed.