And now for something completely different

Without elaborating much, this is a conversation I had via email with my cousin, a retired Washington D.C. attorney with an encyclopedic knowledge of film, and his friend from Kenyon College, Dave Roberts, who is an expert on math. We were trying to figure out whether or not there are random elements in great art, whether they matter, and then, eventually, whether or not art is fundamentally about “newness” or about something else. I also got sidetracked onto the subject of freedom and free will. Somehow all of this seems tied together, but I have a hard time connecting the dots. When Brian veered toward his distinction between “newness” and fundamental value, in creative work, he got close to what seems to matter quite a bit in the world of visual art right now, to the detriment of quality. Over the past century, the world of visual art has idolized the New, and Brian’s unabashedly ultra-conservative position on the world of film, in particular, is that this has done almost nothing but corrode the intrinsic value of the art form. Godard is something of a villain in Brian’s world. For him, substance is all that matters, and that substance—story and character, essentially—can be as old as the ocean. Newness is beside the point. Yet, the way I look at it, when you see great work, you have a sense that you’re seeing something for the first time, and that feeling of freshness, of seeing something anew—that’s a component of creative experience that’s essential to what art is. It means the work is alive, and you’re alive. Define that word “alive”, or that feeling of “new” for that matter, and you’ve unpacked all these issues and made them clearly understandable, but that’s a tough job. I’m just not sure how great art works, what it ultimately “means”, why it seems to be impossible to mechanize—and what all these questions we explore here actually mean in relation to human behavior and human experience. But I’m pretty sure the best art tries to manifest what it means to be alive and it involves all of these issues we were addressing.

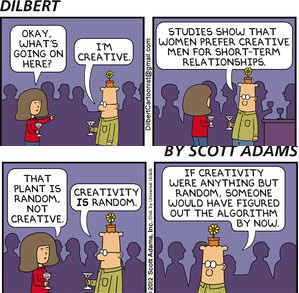

Brian: I don’t read the comics as regularly as I once did, but last Sunday’s Dilbert caught my attention. In it, Dilbert espoused the following theory of creativity: “Creativity is random. If creativity were anything but random, someone would have figured out the algorithm by now.”

Comments? Agree? Disagree? Why?

(The detailed views of engineers and math majors will be particularly welcome, although the views of creative people will also be welcome.)

DD: I think, as in all other productive work, creativity is largely routine, with a very small portion of random insight thrown in, when the work is superlative. The problem is when the random elements are totally absent and you get commercial trash, basically. A lot of very good artists have totally eliminated the unpredictable elements and simply keep turning out trademark work, based on their own set of invariable stylistic rules. In large part, this is most of what artists do, and it can turn out some great work, as well. In a movie, the “random” elements are likely certain traits in a given performance or performances that no one could have foreseen, even the actor. In music, jazz is where the “random” is probably more essential than in any other art form. The Dead during one of their long jams. Everyone recognizes that what they are doing is in some way, at certain points, “perfect” and yet no one could have predicted they would be doing exactly that thing when the song began, especially the musicians. The “random”, in that sense, is essential to great art, because the quality of it often surprises even the one producing it, and so it isn’t simply a mechanical outcome of a set of invariable rules, but at some point, risk and improvisation found a way into the process and gave it a fresh life that it wouldn’t have had without that element. But mostly art is the application of extremely routine, rule-bound, dutiful, tedious hard work.

Dave R.: Here’s my initial reaction. Dilbert is saying that no one has figured out how to be creative on command. That is, no one has a sure fire method (i.e. an algorithm) for producing a never before seen object in whatever field one happens to be working in (art, science, mathematics, engineering, etc.). As I write this it strikes me that this topic has a close connection with a vexing issue that we have often touched on without making much progress: novelty. Because how can we possibly dub some act creative without its being at least a bit novel? But are there not degrees of novelty? Consider creativity in engineering, rather than art. Suppose I am a civil engineer in charge of building a bridge. How much creativity is involved? Not much, one might hope. Probably be best if I built the new bridge as close as possible to other bridges known to be successful. Copy as much as possible. And copying would seem, at first blush, to be non-creative. But nevertheless, my bridge has to satisfy unique conditions, similar to but not identical to other bridges. And I have constraints with regard to expense and available materials and labor, again similar but not identical to other bridges. So as an engineer I am taking quite a bit from my predecessors: knowledge that certain things are possible and that certain things are likely not; patterns for organizing the work; ideas for where to get resources for labor and materials; and perhaps a sort of general inspiration regarding bridge building. And to all this I bring, what? I would argue that I do need some spark of creativity to handle my unique conditions of time and place. Perhaps not as much as earlier bridge builders. And certainly not as much as the first bridge builder!

What I have described above does not seem very random to me. And the question is, how much of the above is analogous to artistic creativity? It seems to me that in an awful lot of art there is much the same copying of predecessors. People can learn from their predecessors that it is possible to paint a picture, write a novel, or make a film, and the more they look at their predecessors the more they learn. And while this process of learning is perhaps not so cut and dried as a mathematical algorithm (do A, do B, do C), I would not call it random. But perhaps we want to reserve the word creative only for the major leaps, the dazzlingly new. Or only to the unique touches that an artist brings to his or her medium, however much that artist has borrowed from the heritage. And it’s these unique touches that are random, and cannot be learned or taught.

DD: Agree. Most of creative activity is copying, or doing something you “know” how to do, yet in fresh work, some element is unpredictable, even to the artist. That’s what I would call “random” because it isn’t predetermined at the outset of the creative work. Call it “inspiration” or some other lofty name, but it’s still a random, unpredictable element that makes the work seem somehow new, or new-ish. I think almost all work is newish, not new, and is in fact mostly the application of principles or rules from previous work in the same genre, with some kind of modification that holds attention. A creative genius comes along, like Shakespeare, and lifts most of his stories from previous sources but applies so many unpredictable, “random” new elements, through his voice, as he filters them through his mind, that what he does feels totally original, because his “voice” is so unfamiliar, with such an enormous capacity to handle the English language, compared to what has come before. Proust is another case, where he’s doing a multitude of things previous writers have done, if you look at small portions of his book, up close, but stand back and you see he has arranged everything in such a way that the impression you get of the overall work is totally unique. And again, the voice, the whole personality, of the writer offers you a sense of something totally new. Random isn’t the most accurate word for that element of newness, but it’s related somehow to randomness. You have to get into finer distinctions: what makes a writer or painter seem “original” is that the entire output seems to belong to and bear the imprint of that creator’s consciousness or personality. You can hear Faulkner in everything he wrote, and Hemingway, and so on. But the essence of the stories they’re telling resemble many other stories before them. New elements of so much poetry and painting and music seem random because they can’t be predicted based on what the work sets out to do: they’re surprising. Yet overall, the story is X or Y or Z, which has been done before in some other guise.

I wonder if what we’re trying to get at is something for which there isn’t really a word. But it’s the heart of what makes art vital and interesting and valuable: that sense of vitality and freshness in work that feels “original” and yet, if you examine it, isn’t really totally original at all. It seems as if this is sort of the heart of what makes creative work compelling, this combination of familiarity with freshness: there really is nothing essentially new in most new work, and yet it feels new and fresh. You’re telling stories that have been told before, in other forms, yet they feel slightly unfamiliar and that’s what makes them interesting. That unfamiliar quality is where I would look for the random elements. And is there really any way to mechanize that, to make it the outcome of invariable rules: an algorithm for creative work, as Dilbert puts it.

Interesting thought occurred to me: what exists between chaotically random and rigidly predetermined? I’m not sure science recognizes any middle ground, but it’s where human freedom seems to exist, or at least the impression that we have of freedom of choice.

Brian: The thing that caught my attention about ‘Dilbert’s Theory of Creativity’ was the use of the word ‘random’ to define ‘creativity.’ You both seem more or less to accept the validity of that word choice (e.g., DR – ‘unique touches’ = ‘random’; DD – ‘not the most accurate word, but close’). I had more or less the opposite reaction.

As is almost always the case when one gets mired in the world of language, we are primarily dealing here, I think, with the question of what words mean, in this case two of them: ‘creativity’ and ‘random.’ We probably all have more or less the same idea in mind about the meaning of ‘creativity,’ but here’s what my handy, dandy MS Word Encarta Dictionary (North American version) has to say about the meaning of that word, beyond the purely tautological: “the ability to use the imagination to develop new and original ideas or things, especially in an artistic context.” That’s a reasonable definition of the common understanding of the word, I suppose, not the best one I could devise certainly, but close enough for government work. And it defines ‘creativity’ entirely in terms of what’s ‘new and original’ (‘original’ being just a way to repeat ‘new’ with a somewhat different and more ‘human scale’ shading, it seems to me). Mr. R has used the term ‘novelty’ (perhaps due to its close kinship to the word ‘novel’) to express the same idea. My own usual word choice in this context is I think ‘innovation,’ which carries perhaps a connotation of ‘technological advance’ that also is not ideal. Mr. D, on the other hand, seems to maintain, with Joseph Campbell I suppose if not also with Solomon, that there is ‘nothing new under the sun,’ at least when it comes to the basic ‘forms’ of ‘stories,’ although not when it comes to their specific embodiments. (In this view he is equaled and surpassed by the great contemporary narrative filmmaker Béla Tarr, who has written: “all stories have become obsolete and clichéd and have resolved themselves. All that remains is time.”) And so from inquiry into what ‘creativity’ means we are led to inquiry into what ‘new’ means, and then on to the question of whether something ‘new’ – and hence whether ‘creativity’ itself – is even possible, and if so to what (perhaps rather limited) extent. There is also, of course, another difficulty here. What is ‘new’ to me may be ‘old hat’ to you. The man who has heard ten thousand stories (and remembered every one) will find repetition (‘copying,’ to use Mr. D’s word) in stories that are completely ‘new’ to the man who has never heard a story before. But while the man who thinks an old story ‘new’ because he has never heard it before may experience the illusion of ‘newness’ (and hence of ‘creativity,’ if our definitional foundation is secure), that is all he will experience – an illusion. For the story is not in fact ‘new,’ but instead is very ‘old,’ as the man who has heard ten thousand stories (and remembered them all) well knows.

This short process of thought causes me to wonder about the validity of defining ‘creativity’ wholly or even primarily in terms of what is ‘new.’ I am drawn to question whether what we really mean when we say ‘creativity’ is not something defined at least in part, and perhaps in major part, by the question of the basic value of the thing, whether new or old or somewhere in between. Placing, as Dilbert did, a flower pot on the top of your head may or may not be ‘new’ (one could easily maintain that it’s just an unoriginal variation on the old ‘lampshade’ or some similar bit), but assuming it is new, does that make it creative? I wonder. Actually, I don’t wonder. I just don’t think it does, at least not in any meaningful sense.

Now to what is really the main event here – the thing that prompted my original questions, the use of the word ‘random’ in this context. Here is what my handy, dandy etc. MS Word dictionary says about ‘random’: “done, chosen, or occurring without an identifiable pattern, plan, system or connection.” It surprised me rather a lot that you both appear to accept the use of the word ‘random’ in the context of a definition of ‘creativity.’ Mr. R identifies the ‘unique touches’ that make up (and perhaps frequently or always alone make up, given the above) ‘creativity’ as being ‘random’ elements. He does this, apparently, because he views such elements as ‘unpredictable.’ (He also says that such ‘unique touches’ ‘cannot be learned or taught,’ and I do wonder about the basic accuracy of that statement. Possibly, he means only that ‘how to come up with a “new” “unique touch”’ cannot be learned or taught, but I wonder about the basic accuracy of that too.) Mr. D, similarly, identifies the ‘unpredictable’ or ‘unforeseeable’ results of ‘improvisation’ – and by extension I suppose all results of creative endeavors that are arrived at by some process analogous to ‘improvisation’ – as ‘random’ elements. He also says, however, that ‘random’ is ‘not the most accurate word,’ but that it’s ‘close.’ To me, it is not the right word, and it is not ‘close.’ Return to that ‘main definition’ that is I would assume what people usually mean when they say ‘random’: “done, chosen, or occurring without an identifiable pattern, plan, system or connection.”

This seems to me not only to not be what ‘creativity’ is, but to be some approximate opposite of what ‘creativity’ is. The ‘pattern, plan, system and connections’ of truly ‘creative’ works are not only not absent; they are so remarkably present that they make up the very essence of the thing that is ‘creative’ about the work. Don’t they?

So, I reject Dilbert’s theory of creativity. Creativity is not ‘random.’ Nor is it what I would suppose to be the result of the ‘random’: chaos. It is, in fact, the opposite thing. It is the imposition of a kind of order on what may well be (or may well not be – who knows?) the truly ‘random’ and thus chaotic nature of ‘what is.’ And the kind of order imposed is a kind of order that has value to human beings. That, at least, is a short version of my perspective.

DD: I agree with Brian, but the problems we’re having I think arise from the false dichotomy between predictable, rule-generated work and “random” creativity. We need another word to do a better job for what the word “random” is doing here. New, original work, has the freshness of apparently random behavior, because it’s to some degree unpredictable. My reaction to great new work is often to think, at least subliminally, “How did he/she do that?” Or “How did he/she think of that?” It’s like a magic trick. You can’t clearly see the mechanism that built what you’re observing. With Matisse I can see exactly how he applied his paint, much of the time, but his choice of where to put that paint: that’s what’s so amazing. Other work, with Edwin Dickinson for example, I often can’t actually see how the paint could be applied to create what I’m seeing. Yet, Brian is right, there are principles of order behind all of it which are in some way a new combination of previous principles, and the difficulty of discerning those principles, the personal rules an artist has followed, are maybe what gives rise to that feeling that you’re looking at something entirely new. Looking at Picasso’s work as Cubism began to emerge, if you don’t realize how much he was indebted to African masks, you would think you are looking at something far more radically “new” and, at the time, probably offensive to the average European, than you would have felt if you’d known the antecedents of those images. His originality was to combine Western oil painting, representational painting, with elements from an entirely different tradition of making images, with entirely different motives: the masks weren’t made for the same motives as a work of sculpture in Europe. Something similar happened in the 60s with music: the convergence of completely different musical traditions, giving birth to rock and roll. Old elements combined to create something familiar in its parts, but new in the way it was put together. And then you’re on to all the contemporary questions about postmodern sampling of previous work, where dependency on the past and creativity through consciously commenting on what has come before, can get very very boring.

Yet it seems that what’s most original, or unique, in a given artist’s work is indefinable, something whole, which can’t be dissected and explained in a mechanistic way. Which is implied by what Brian says here: that there’s a principle of order, not randomness, in great creative work. Yet if that principle isn’t just the deterministic outcome of predictable forces—if it were, would it feel fresh and surprising?–and it isn’t random, then what is it? It seems that this really is similar to the question of free will: what does it really mean to make a free choice? Is it the ability to choose to obey a high principle of behavior, as opposed to a destructive one? If so then it isn’t really free, it’s obedience to a rule, right? Or is it something else besides obedience to a rule, without being just chaotic, random impulsive self-indulgence. What kind of behavior exists in between the apparent extremes? That seems to be where great creativity lives: this craving for a kind of order that’s somehow liberating. This is a paradox. How can order, with its principles and rules, be liberating? How can order produce something that feels new? What is that newness? I always go back to the seasons on this subject. Every year the beginning of spring: it’s always the same thing. Flowers come up. Leaves come out. Birds begin to sing. It gets, well, warmer. Smells return! OMG, that sounds trite and boring, the way I’ve put it. I’ve seen and heard it all before. Yet it always feels absolutely new and totally liberating. I come alive again along with the world. Why? Whatever that “life” is, that living presence, which is the same as it ever was, that’s all that “new” art needs to be about.

This post made my head hurt.

I think there is a randomness to creativity, but randomness is not necessarily creative. Sometimes it just results in a tangle of chaos, as do some creative efforts. I think of creativity as a state of mind, not unlike the way you approach problem solving. Not all problems need to be approached as if they have never been solved before, but previous approaches can inform a new one. That can result in either a quicker solution than if you’re starting from scratch, or possibly a better solution, as you are coming up with a solution based on previous experience, either your own or others. While I believe we rarely learn from the mistakes of others (look at history), our own mistakes can/should inform our own solutions.

When it comes to the act of creativity itself, I think there are a couple states of mind going on at the same time. The act of painting (in my case) is (or to my mind, should be),both a craft and an act of creativity. This is somewhat removed from the conception of a painting to begin with. Both states can involve creativity. And both can be reduced to repetition.

Finally, I believe the creative state of mind, informed by personal history, awareness of the past, a searching for the path, can all lead to an evolution that can appear random. I suppose may be random. But for me it is more of a trickle, punctuated by leaps–like floating debris–in one’s ability to conceive of original ideas, and to handle materials in new ways.

Ouch. I prefer the ease of bitching about Morely, though this is an interesting conversation. I think it is mostly the typing that makes it tough for me. It (typing) is not my craft.

I think I agree, Rick, but I guess it seems that maybe “random” elements in the process simply have that appearance: what feels fresh often doesn’t seem to follow from what’s happened before, so it emerges, as if by some random event. Yet it’s a part of a coherent process in the end, part of the order that exists in the finished work. I do think that creative people stumble onto solutions or new ways of doing something that involve fairly unpredictable results, which turn out to look “just right.” AbEx was sort of built on that sort of thing, wasn’t it? Let the subconscious take over and leap forward, taking risks and hoping the image will emerge: there’s just a bit of that in the most conservative brushwork, if it’s a vigorously applied mark. Yet something in the artist is guiding the way paint gets applied, so it isn’t simply chaotic, though it isn’t necessarily conscious or even repeatable in precisely the same way. Again, the word “random” isn’t right. But it’s in the direction of what’s going on when the painting takes on a life of its own . . .