Anything goes, part two

Having just finished rereading After the End of Art, by Arthur Danto—I quoted from it in my previous post—I remember why I had such mixed feelings about this book the first time I read it. The history of art is over, and we’re now free to do anything we like. That seemed to be his vision, through most of his book. If a work is visible, it can be considered art. So anything is possible. Yet, in his last chapter, he suddenly lowers the boom and says that yes, visually, anything goes, but that doesn’t mean that we’re free to do anything at all. Essentially, you can work with styles and tropes from the past, but you have to put it all in brackets: it has to be ironic. If it looks exactly like a Rembrandt, and it was painted last year, call someone for some emergency deconstruction. Namely, someone with Danto’s credentials.

The sense in which everything is possible is that in which all forms (of visual art) are ours. The sense in which not everything is possible is that we must still relate to them in our way. The way we relate to those forms is part of what defines our period . . . one can without question imitate the work and the style of the work of an earlier period. What one cannot do is live the system of meanings upon which the work drew in its original form of life. Our relationship is altogether external, unless and until we can find a way of fitting it into our form of life.

That last phrase sort of opens up all the possibilities again, in a sneaky way: “unless we can find a way of fitting it into our form of life.” Well, duh. These passages I’ve quoted above strike me as incredibly awkward attempts to dance around the phrase “form of life” as a way of remaining true to the postmodern orthodoxy. There is no universal truth; there are no eternal verities in human life. We’re all simply living through a period in which fleeting cultural forces have shaped our behavior and thinking, and we need art that addresses these temporary economic, social and sexual realities, unique to our time, until they are gone and the work we’ve done becomes a fading way of making sense of our “form of life.” So, Danto at first says that history is essentially over, for art: artists are liberated to do absolutely anything and call it art. (Whether it gains cultural traction through the respect and admiration of others is another question.) Yet then he reverses himself and says artists can’t simply make art the way previous artists did, because that “form of life”—ancient Athens, say, or Renaissance Italy or ancien regime France—no longer exists and the art of that period represents its own matrix of meaning that has no application in our postmodern world. In one sense, this is obvious. I don’t spot many togas in the public square anymore, though I could find them with a repeat viewing of Animal House. So I’m not eager to have a painting of anyone in a toga. But does that mean Greek art is meaningless to me? His examples of how one is prohibited from doing work almost exactly the way previous artists did it are, for me, peripheral and ultimately trivial.

He offers two examples: an account of a 20th century forger who attempted to sell his output as the work of Vermeer and a postmodern painter who deconstructs previous work and reassembles essentially a visual mash-up using imagery from different historical periods. For Danto, if you are drawing from the past for technique or motives, you are either a crook or a jokester. Kehinde Wylie would be a great example of the latter: creating his amusing and yet visually striking portraits by appropriating poses for his sitters from previous great work, and then having his assistants render some faux wallpaper for background. As much as I like Wylie, he feels like a lightweight virtuoso, a crowd pleaser—I find myself pleased, as far as that goes, along with the crowd. But the scent of passionate inner necessity doesn’t hover much around this sort of work. The way Manet was obsessed with Velasquez and struggled to do work equal to that previous artist’s brilliance remains a great example of how the past exerts pressure on the work of current artists, and there is nothing ironic or postmodern in Manet’s attempt to internalize and be worthy of that Spaniard’s work. By wanting to be Velasquez, he became himself.

All of this emphasis on how an individual’s historical period entirely defines his or her art strikes me as postmodern boilerplate. I had a lunch with A.P. Gorney in Buffalo not long ago, and we followed up with a few emails about precisely the sort of assumptions that underlie Danto’s philosophy. I mentioned thinkers who sought for universal structures underlying human experience across all cultures: Jung, Joseph Campbell, Aldous Huxley, and Claude Levi-Strauss, for example. I suggested that fundamental human experience, across cultures and down through the centuries, consists of far more universal characteristics and common denominators than culturally unique characteristics. He laughed and dismissed the notion at lunch and continued to do so in our email exchange. I stood my ground though:

I think art matters, otherwise I wouldn’t be doing it, yet it’s an interesting challenge trying to put into words exactly why. You end up using words a good postmodernist would toss out of the lexicon immediately: real, reality, authentic, honest, good, etc.

I do think someone ought to do a book that tries to answer the question: what experience connects all cultures and all people around the world. You could start with death, time, solitude, friendship, love, anger, rain, dreams, hatred, resentment, envy, sex, weariness, joy, hunger, despair. . . the list goes on. Isn’t there obviously, simply in this list, evidence of an underlying commonality to human experience that cuts across all political, religious, and cultural divides?

And historical eras, as well? When “form of life” means “being human” then great art from any time remains powerful and relevant. When Issa writes about a fly wringing its hands on a windowsill, I become that fly as quickly and readily as a Japanese reader two centuries ago. I am the same reader. I was making a slightly different point with Gorney, but my response to Danto is rooted in the same notion that the most fundamental human experiences—in other words human nature itself–haven’t changed much since civilization began, and that the advent of electronic technology hasn’t yet altered human nature to the point where a block of marble carved exactly as a Greek sculptor would have carved it has little to say to the contemporary viewer. Or a long-suffering sitter, for that matter. The marvel of the human body hasn’t changed much at all in two thousand years—we’ve gotten slightly taller over the years—and a replica of it in stone remains just as much of a marvel too, in and of itself. That no one has the patience anymore to carve stone this way is maybe the outcome of electronic technology, but that’s simply a commentary on what the deluge of meaningless digital stimuli has done to our brains, not an assessment of whether the torso of a human being in stone, in the Greek manner, actually has different meaning for an Athenian compared to someone in the 21st century. I tend to think almost all of what such a sculpture conveyed in the ancient world remains as powerful and relevant as it did back then. And I would go down the list and say the same thing about someone who might turn up with Rembrandt’s skill in chiaroscuro, along with his insight into human nature and ability to convey the inner life of a sitter by rendering a sitter’s eyes a certain way in oil—do all of that with a subject now and you would have an equally powerful and relevant work of art about what it means to be a unique human individual in any century. For someone who could paint now as Rembrandt did then, the fact that she draws her technique and some of her motivation from a previous era matters far less than whether or not the painting actually does what Rembrandt’s portraits did. The Vermeer forger’s work failed because it didn’t match the quality of the original artist’s. That was the problem. He didn’t have the same genius. A man who could actually paint a Vermeer, this year, is someone whose work I’d be eager to see.

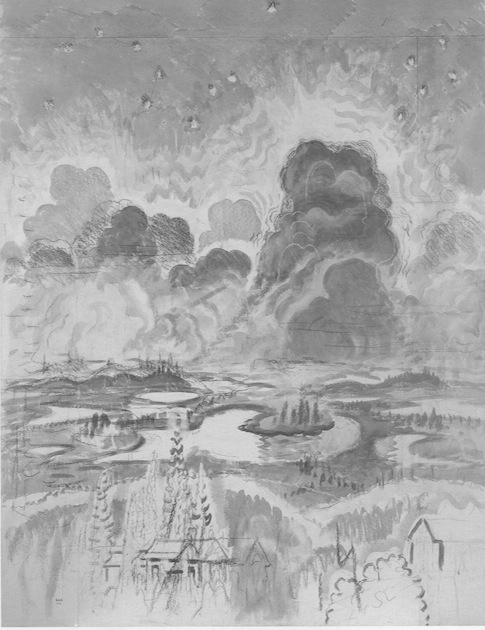

When it comes to the way the past flows into the future, through individual tributaries of younger talent, I think of Charles Burchfield as a prime example of how new work is rooted in tradition and makes its historical period almost irrelevant. He serves as a good answer to Danto—or maybe an example of what Danto believes artists actually can and should do in relation to the past. Burchfield internalized the work of previous artists and made it his own. He wasn’t trying to comment on past art. He was struggling to use what it taught him to convey his Romantic vision of a mysterious underlying presence in the natural world that defies rational analysis. Burchfield had many unique stylistic conventions—such as creating visual symbols for heat waves and the sound of insects. At face value, a little goofy, maybe, but it worked in a poetic way, and he created a stylistic niche for himself no one can pilfer without becoming a mere imitator. Try it sometime and see how it goes. Yet his entire approach to creating a landscape owes more to Chinese painting than any other tradition. Danto claims no one could paint now as one of the Chinese literati painted back then and get away with it. Granted, Burchfield didn’t do work that would be mistaken for Chinese landscapes. Yet he came close to doing what Chinese artists did, in his own way, as he spent his life trying to match the beauty and mystery of scroll painting, driven by similar motives and creating images that resemble Asian work in many ways. He came closest to fulfilling this ambition toward the end of his career, as the marvelous Whitney retrospective in 2010 demonstrated with Landscape with Grey Clouds (Heat Lightning). It was Burchfield’s most successful attempt to capture the sense you get in a Sung dynasty landscape that earth and heaven have melted into one continuum—and it works as a painting, because Burchfield painted it. Not because it was painted in the early 60s. It didn’t open up a new field of activity for anyone else, necessarily, or found a new school or movement. It was, simply, a Burchfield, with all of his peculiarities and yet this essential link to work that had been done before. Burchfield’s devotion to art from a previous century and an entirely different culture works in a way that is neither forgery nor a joke: it’s the internalization of a sense of purpose, and a tradition, which becomes transformed through the artist’s inner necessity. His antecedents were assimilated and digested and became the fuel for his own similar and yet slightly different work—a peculiar kind of individual stylistic evolution outside the course of what was supposedly important in Western art at the time. That quest and struggle ought to serve as a model for all painters now (though he established a market by what I’ve always considered an act of selling out, on the side, doing dismal realist work which was lumped in with Hopper and others during the Depression years. It looks cartoonish to me. On the other hand, he also looks cartoonish, but in a good way, with his most original work.) Burchfield stands as one of the most original American artists, though his originality lies simply in the way he combined his influences, his passion for previous work, while merging these influences into a style all his own, which seemed to have little to do with the realities of his historical period. His images of nature could be seen as an anticipation of the back-to-nature Romanticism of the hippie movement, but that’s pure coincidence. When and where in the world it was painted hardly matters at all except to an academic.

[…] any painting he did, other than one particular landscape in the phenomenal Whitney retrospective, (Heat Lightning,) this work fulfills Burchfield’s lifelong yearning to be a classic Chinese scroll painter […]