Insalaco steals the show

Thomas Insalaco’s new painting, on view at Oxford through June 1, is a beauty. It feels like a step into a new frontier for him, an advance toward something even more intriguing than what he’s done up until now. I’d walked through most of the show before I finally paused in front of this large oil, and I was stunned by it before I even realized who’d painted it. So much of Insalaco’s career draws from his love of Caravaggio, so the ambiguous complexity of this painting’s composition and color threw me off the scent. It’s not a bright image—much of his work looks and feels dark—yet the baroque murk that always lurked behind so many of his foregrounds doesn’t swallow any detail here. Even in the darkest passages, he has spent a great deal of time lovingly rendering significant and beautiful detail.

I have a lot more to say about it, but first some praise for the exhibit as a whole. Jim Hall has assembled an especially strong invitational show, built around Galen’s philosophy of the four humors: sanguine (pleasure-seeking and sociable), choleric (ambitious and leader-like), melancholic (analytical and thoughtful), and phlegmatic (relaxed and quiet). The ancient four elements—earth, air, water, and fire—can be aligned with the humors as well, and some paintings in this show take advantage of that. I liked the theme from the start, and, with the notion of earth/melancholy in mind, I painted Skull Unearthed Circa 1930—which will also be on exhibit in the Rochester-Finger Lakes exhibit at Memorial Art Gallery this year. Not everybody warmed up to the show’s theme as quickly as I did: I encountered some head-scratching about it at first from Brian O’Neill, for example who ended up contributing a fine abstract to the show. It’s clearly a stretch to see the connection between some of these paintings and the four humors, but that’s part of the fun with Jim’s themes: how, and if, you can connect the dots. Matt Klos submitted a tiny, pleasingly muddy painting of jars, which I actually like for its enigmatic brevity, yet to entitle it Air seems a bit like giving it an alias in order to smuggle it through the door. (Glad he did.) Some personal favorites: Evening of the Cold Heart, Fran Noonan; Ascension #2, Bill Stephens; Ain-Yesh #9, Jack Wolsky; Earth and Air, Deborah Hall; Cuarto, Jappie King Black; I Mavri Stigmi, Bill Santelli; Flight, Alice Chen; The Gatekeepers, Ray Easton; and A Sanguine Temperament, Karl Heerdt. Many other pieces are among the best work I’ve seen from the artists who regularly contribute to these shows. Chris Baker’s Under the El pushes his representational skill even more toward abstraction than any of the work he showed last year, without losing the quiet drama of the construction scene he captures: the use of gouache reduces some of the blending that oil would facilitate increasing the sense that lights/dark, warm/cool areas snap and fit into a perfect, taut balance that doesn’t give the eye anywhere to rest for long. The eye dances around the image the way it does in front of Stuart Davis.

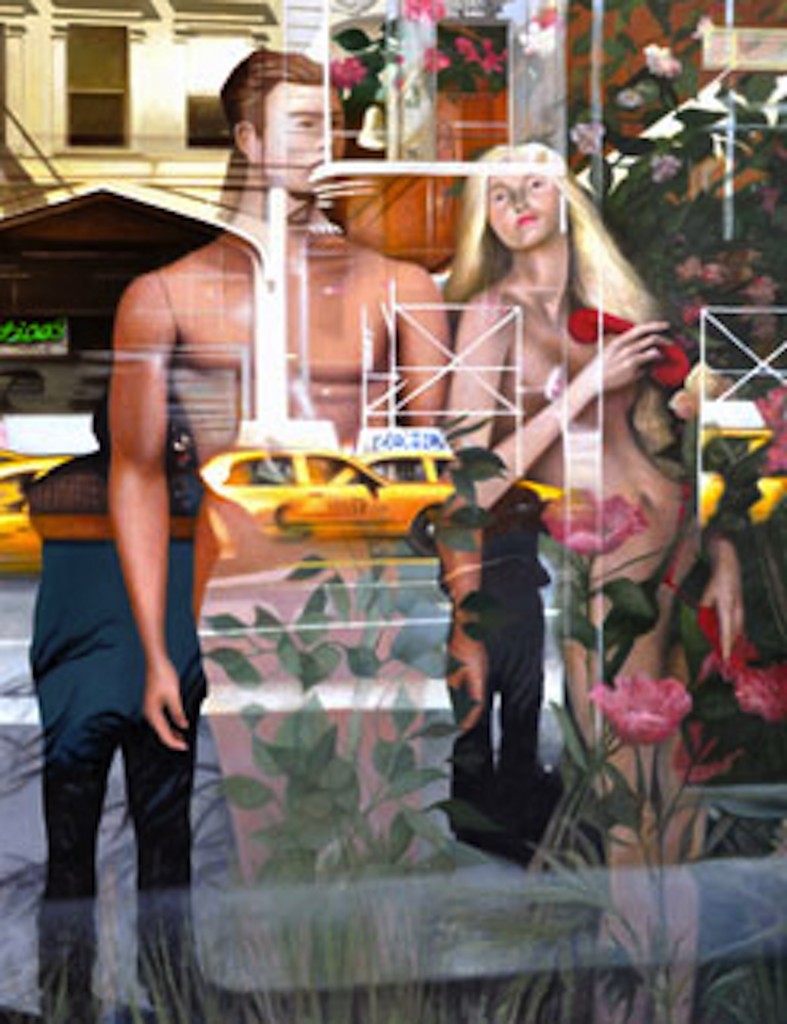

Something similar happens with your gaze when you begin to study Insalaco’s Adam and Eve on West 57th St. Jim Hall and I sat and talked about painting for a while, mostly with Insalaco’s painting in mind.

“Maybe it’s the Hegelian in me, but when someone asked recently what I look for in a great painting, I said it’s the ‘antinomies.’ I don’t think it’s what they were expecting,” he said. Hall seeks seemingly irreconcilable qualities: the way the physical quality of the paint itself steals attention from the image it conjures up, for example. Jim always favors the idea that what’s happening in a great painting is under the artist’s technical control, and I always stress how all the controls have to lead up to an unrepeatable combination of factors which can’t be regulated into the processes of a particular style. Again: an antimony. The style is there, the way the sound of a person’s voice is there in everything she said, yet that identifiable quality isn’t entirely conscious or intentional. As a way of conceding a little to my point, on a different level, Jim agreed that an artist can do something well without having to understand all of the implications of the finished work. “When I was at Penn, Joseph Heller came to talk and a member of the audience got up and spent what felt like twenty minutes explaining what Heller’s book meant. It seemed insufferable at the time. Yet Heller let him go on and then nodded and said, That sounds about right. I’d just never thought of that.” An artist needs to know how to make an image work, not predict all the ways it will be understood. And a balance between representation and abstraction relates to Jim’s notion of “antinomies. ” An image lies somewhere on the continuum between the extreme of photographic accuracy and flat geometric pattern—and those two poles pull against and work with each other in every painting. “Klee said, more or less, that pure abstraction was impossible. As soon as you make a mark, you invoke images and feelings and memories. You can’t get completely away from it.”

All of these thoughts apply to Insalaco’s painting, many times over. It’s one of those images that seems laden with inexhaustible possibilities for interpretation. It’s a dizzying confederation of opposites fused into a single image, not just visually, but intellectually. It appears to be a painting that faithfully renders a photograph Insalaco took, standing with his companion on a sidewalk in Manhattan, with his camera pointed into a department store display of two naked mannequins. He represents them as Adam and Eve, with a red telephone in Eve’s hand, a sort of amalgam of serpent and apple. Here’s one of the practical difficulties of the painting, and one of its ironies. It’s pretty obviously a painting drawn with great fidelity from a snapshot Insalaco or his friend took on a visit to New York City. Yet when you, the viewer, take a photograph of the painting itself, its unity as a painting seems to break apart into all the jangling artifacts of casual photography and much of what’s amazing about it gets lost in the limitations of your camera’s exposure. In the photograph I took of it—Jim observed the same thing when he tried to shoot it for publicity—it looks as if the painting is badly lit, marred by glare from the gallery’s track lights, but that glare is actually part of the painted image itself. So you realize you’re taking a photograph of a painting of . . . a photograph . . . which is actually a picture of at least two separate images superimposed upon each other: the reflected street scene and the diorama behind the glass, where two naked mannequins await their next wardrobe. What also gets lost in the photograph I took: all the rich, delicate detail in the darker lower areas. The surface of the painting offers a beautiful, sinuous network of flora, rising up from the bottom, and you wonder if this pattern was part of what Insalaco actually saw or is he simply imagining a garden in the middle of this city? It’s as if someone has attached a kind of transparent wallpaper to the backside of the glass, covering it with waves of leaves and blossoms, a Garden of Eden reduced to this flat scrim hovering somewhere between the actual space behind the glass and the ghostly reflection of the street with its river of yellow cabs. (The word GHOST, an ad for a broadway play, rides atop one of the cabs where one often finds an advertisement for Manhattan strip clubs on many cabs; another wry irony buried among so many others here in this painting of two modestly represented nudes.) The male figure is clearly a life-sized doll. You can see the line, the seam, between his arm and his shoulder, where the plastic parts have been socketed together. Yet Eve’s shoulder looks smoothly human. Is an actual woman posing with a lifeless dummy? Could this be a shot of a performance? The longer you look, the more the questions compound themselves. Insalaco has adopted one of the great myths in Western culture, the Garden of Eden, the Fall, Original Sin and both emptied it of its meaning and somehow used it to point a finger toward contemporary American consumer culture: here they are, the prototypical human beings, but naked and lifeless, with the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge having taken the shape of an old-school telephone, itself the prototype of everything that has narrowed our awareness now. The media, the Internet, Web 2.0, iPhones . . . the endless, mindless stream of images and chatter.

What’s most remarkable for me about this painting, though, is that it miraculously hangs together, despite how incredibly busy it is. That’s the biggest “antinomy” here: the courage it must have taken to risk the incoherence so many visual elements would usually generate and somehow unify them. Without quite understanding why, I told Jim it reminded me of Chagall’s cubist period, when he did those enormous paintings of himself and his wife floating over Vitebsk, or floating through a room like smoke. At that point in his career, Chagall was trying both to conjure a dream and yet be incredibly precise with his edges, his forms, in order to conveying a sense of something entirely outside his experience: zero-gravity space, as a metaphor of love. He and Insalaco both succeed in their attempt to convey an absolutely convincing sense of unreality, a world that behaves in perfect obedience to its own secret rules. Those Chagall paintings work, as is the case with much of Cubism, by calling your attention to the surface, the paint, all the demands of the surface even as they create a sense of fractured depth. (That antinomy again.) Which is exactly what you get here: you are seeing two or three or even four different kinds of space, outdoor and interior, urban and idyllic, staged and accidental, imaginary and actual, and yet they are completely interpenetrated, each fused with all the others. Ordinary space and time dissolve and the composition flattens everything out to the point where it seems you’re almost gazing at a tapestry. Adam and Eve on 57th St.is genuinely a tour de force.

Comments are currently closed.