Under the influence

I found the current show at Freight + Volume both disappointing and encouraging, which, if you think about it, ought to be a hard thing to pull off. It was a bit of a letdown in a way that I’ve experienced several times over the past couple years. It goes like this. Paintings that intrigue me when I see them reproduced on a website look much less vibrant and resonant in person. They aren’t as alive as I expect them to be. A surface richness I think I see in reproductions isn’t there when you stand before the actual work. (I remember reading an account of this same experience from someone who had gone to a show of Natalie Frank’s paintings.) It happened, for me, at Walton Ford’s most recent show at Kasmin. I still admire his scenes as much as ever, for many reasons, but I’d expected to revel more in his paint handling. Standing a couple feet away from the images, I wasn’t as charmed by them. Do I quibble? Probably. Would it matter to anyone other than a painter? Probably not. Yet, in some way that’s hard to explain, I felt a little conned at the surface level of the work. His interest didn’t seem to be in the paint itself, but in simply creating the illusion he wanted, as expeditiously as possible. Those same words could be applied as high praise for the work of Sargent or Hals or Vermeer or Fragonard any number of other painters—mastery often means getting the most powerful results out of the least effort. But up close a Vermeer remains as much a marvel of execution as it is from five feet away. Not so much with Ford. His work left me feeling as if the act of painting was something he was impatient to get past. At the recent Durer exhibition in Washington, for example, I never felt that way: even at the level of the tiniest details, each image seemed to vibrate with the artist’s total absorption in the act of bringing his image to life. As much as the finished image, the process, immersing himself in the work, appeared to be, for him, the whole point.

So, once again, at Freight + Volume, I felt this same sense of having been lured to the gallery by work that seemed more technically impressive than it turned out to be. (I’d also felt this way at a recent solo show at First Street.) Normally, it’s the other way around. With Bonnard, I was baffled by the way his work has been celebrated until I finally saw the actual paintings at MoMA and was astonished by the complexity and beauty of the surface—especially the thickness of the paint which made his color infinitely interesting. It’s true of many artists. When I saw Edwin Dickinson’s actual work at the Albright-Knox, it was even more powerful than the impressive reproductions I’d seen.

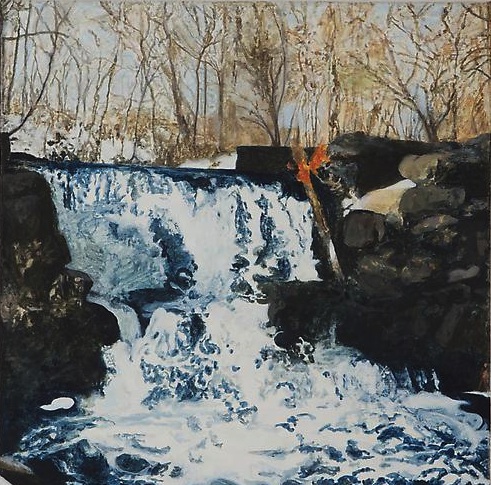

Hoffman’s abstracts were as good as they looked on the gallery’s site, but many of the representational images felt more like studies, the paint thinned to a translucent wash, giving the execution a tentative quality that didn’t keep calling me back to look for more. That may be the conceptual framework behind his whole project—the unfinished quality of any painting. He showed several versions of the same image, with one at a greater state of completion than another, as if to say, it works this way and it also works that way. It just depends on when you decide to quit. His whole approach is conceptual in that sense: he seems to want to illustrate how all painting is simply a personalized reworking of what’s been done before. There’s a nice passage about this in the essay on his work at the Freight + Volume site:

The role Hoffmann plays is to sample these various eras and techniques and styles, much like a rapper or composer edits and samples snippets of other musicians’ work into his own composition. Never exactly copied or appropriated, these works are distinctly painted with Hoffmann’s unique brushwork and paint handling. Despite his multiple degrees of removal from the subject, his specific approach lends an indelible stamp of personality on each one. He sums it up this way: I don’t see the distance between the historical and the contemporary in art as being significant: the context may change, but the content remains the same.

This is actually where the show got encouraging. There’s a heartfelt core to these explorations, as if he’s internalizing what’s been done before and then revisiting it in a fresh way, involuntarily, simply by having adopted styles and images which become new simply by being filtered through his own individual taste and level of skill. In other words, he’s rejecting the conscious pursuit of the New and is simply doing whatever he damn well feels like doing, regardless of whether or not it looks as if an American minimalist or a 19th century landscape painter had done it. In other words, he’s saying very clearly: “Do whatever you feel like any time you sit down to create something. The work doesn’t have to be consistent, stylistically or in any other way, from one piece to the next.” Normally that privilege appears to be reserved for someone who’s already persuaded people who matter that he or she has the brilliance to shift gears abruptly and work in any mode. Picasso, Richter, Warhol all get away with it, because it’s assumed they can do whatever they want. But what Hoffman is saying is that even if you’re only a few years out of art school, you have permission to paint any way you like. It may not help you make money: developing a precisely defined style and producing a body of work that observes the narrow rules of that style is a much easier way to establish a market. Style becomes a brand identity, as a business consultant would say. Along with Hoffman, I say, screw that. If you want to paint the way Courbet painted, or even do your own version of a Courbet painting, it’s all good now. And what’s equally encouraging is that Hoffman isn’t simply trying to do something rooted in the past but which is dramatically and ironically different from its origins—as, say, Kehinde Wiley is doing (and doing exceedlngly well). Hoffman’s work is low-key, understated, subtle, and deeply respectful of all the fundamentals of color, light, and value. There’s a refreshing sense of humility and mystery that runs through all of it. For someone so immersed in work from the past, he offers a lot of hope for the future.

Comments are currently closed.