Be the question

I first saw John Sabraw’s work while visiting with Lauren Purje and Rush Whitacre when they were rooming together in Brooklyn. Lauren treasures a drawing John gave her, a startlingly exact rendering in graphite of a revolver and a syringe. It was hanging on her wall, up near the ceiling—as if she wanted it to be just out of reach. I seem to recall her telling me it was his interpretation of a line from a Modest Mouse song, but what struck me was how uncharacteristically grim it was, an exception to a line of work that otherwise glows with a radiant affirmation of the natural world’s complex unity. I saw one of his Chroma disk paintings, done on a metal support, when Lauren was collaborating with him, which involved destroying John’s painting and doing something of her own on top of it. (Remind me of the dangers of a Purje collaboration if that ever seems like a good idea, not that I expect she’ll ever have any interest in destroying my work.) I recall that John gleefully coached her through the whole thing, even when she complained about how hard it was to paint on metal. Thus I became acquainted with John Sabraw. We’ve never met, in person, but he once told me he loves and admires Illmatic as much as I do, which may not mean much to anyone else, but gave me the illusion that I understand who he is. So I sent him some questions about his work a few days ago, and he promised to answer them. I will post the exchange if he finds the time to attend to it, but he warned that he’s been involved with a segment the Discovery channel is doing on his new show. So, having had my place in the world thus properly adjusted, I’m not holding my breath.

Meanwhile, I got up early this morning to write and, on a Google search for his current show—Luminous at the Richard M. Ross Art Museum in Columbus—I found an interview he did a while back for an earlier show, and one of his comments strengthened my illusion that we have some things in common. He said:

I struggle with the basic metaphysical questions of life: how did we get here, what are we supposed to do while we are here, and where do we go next? I don’t struggle with these questions in an abstract way; I mentally and physically battle to understand them every day.

Now I’m paying attention. Until I read that, I supposed that his art is mostly a reflection of his deep concern for ecology and the environment, about how we fit into the natural world—which is also my friend Rick Harrington’s obsession. John’s Facebook posts on fracking and other subjects would support this view of his art as a subtle kind of social activism, but I’m wondering if his work doesn’t spring from questions more fundamental, questions most artists don’t ever think to ask. The sort of impossible questions a person doesn’t just ask, but becomes. Cartesian questions that cast doubt on the mind of the person asking them. A question like a hot cannonball in your gut. You get the idea. Questions of the sort that tormented people like Wittgenstein, Heidegger and Kierkegaard: an all-consuming doubt rather than an orderly sequence of thought leading to a query with some logically possible answer. Questions that force the conscious mind to face its own limits and gain a sense of the merely supporting role that conscious thought ought to play in a human life. I started painting in my teens because I had one of those cannonballs inside me. It was something like: why is there something rather than nothing. Say what? (Bill Cosby would have smirked and said, if you figure that out, then tell me why is there air?) Of course, there’s no answer, but by asking it you’re begging to know: what is the point of all this? What is life? What does all this mean? Why does life matter? Does it? Why can’t I make sense of it? At a certain age, questions like that can come over you like a flash flood and unmoor you for years, which can be either unfortunate or a very good thing, if it leads to an answer that’s less a proposition than a way of life. In other words, it’s a fertile existential crisis, if you answer it by picking up a pencil or a brush. Art was my way of cooling off that cannonball, and it would appear the same is true with John.

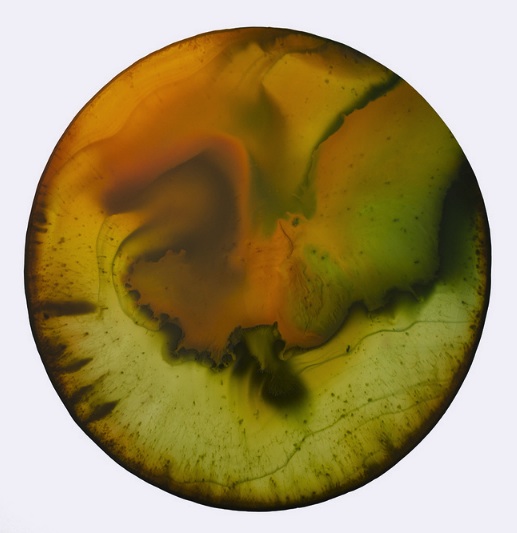

Luminous is almost a single work of art itself, rather than a collection of diverse stand-alone pieces—and John’s work is very diverse, stretching over different mediums and radically different styles, from abstraction to realism influenced by Antonia Lopez Garcia, who is a hero to so many artists I know and admire. At first glance, Luminous is a radiant celebration of the natural, physical world. Yet as you move from one piece to the next, you see patterns emerge, repeating themselves, like fractals, from the tiniest spaces to the largest. With much of his work, he seems instinctively driven by formal imperatives that lead, on their own, to certain kinds of images that tend to be “about” his holistic vision of the world. Mostly he’s fascinated by pure color, yet to achieve certain qualities of color he ends up with images that suggest an advocacy for the natural world. And then, when you think he’s driven to banish gray and brown and black from his visual world, working with the most saturated colors possible and somehow getting them to play well together, here comes the other side he’s suppressed, the blacks white and grays of his meticulous drawings. In the process of pursuing these formal imperatives, work seems to emerge on its own, suggesting the fundamental unity of the entire natural world, where we human beings are just another example of the universal beauty and order, no more significant than anything else around us. With his Chroma paintings, he applies paint in layers and then watches how the paint behaves given certain stresses applied to it, coaxing his images, recognizing what he wants as it appears. They’re sort of Rorschach blots for God. What appears to be a fetus or tadpole has an incredibly detailed cloud formation nestled in the crook of its tail. What could be a head of cabbage evokes a canyon. His interests seem to run from astronomy to atomic structure: some of the drawings in the show appear to have been done from photographs taken using an electron microscope. What you see are, essentially, hints about basic underlying structures that recur at all levels in the world. A river delta recapitulates the patterns of veins in a leaf, or arteries in a heart. If Claude Levi-Strauss had been a painter, his work might have looked like John’s.

If it didn’t require a six hour drive to get there, I’d attend the opening of his show Thursday night in Columbus. If you live anywhere closer, there’s no excuse for not showing up.

Comments are currently closed.