The way of beauty

You cling to your favorite songs and books and paintings the way you once clung to your mother’s hand—because they help you become who you are and make you feel at home. Sometimes, when you see the beauty of a created thing, you recognize yourself in it and want to join ranks with anyone else who loves it the way you do. Last summer, I embarked on a 16-hour journey from Rochester through JFK and LAX to New Mexico—in retrospect, I might have been more comfortable going by wagon train—in order to join ranks, if only for an hour or two, with someone whose books have made me feel a little more at home in the world. Dave Hickey, one of America’s smartest art theorists, was scheduled to have a conversation with his friend, Ed Ruscha, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Tamarind Institute, and I showed up to listen.

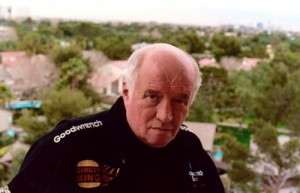

Dressed all in black, with a venti-sized Starbucks coffee in hand, he was more physically imposing than I’d expected, bringing to mind Orson Welles or Harold Bloom, not only in the impression he made just sitting there, but also in the sense of his pre-eminence in his field. Balding, with a tonsured ring of dangling hair around the back of his head, he spoke in a quiet voice full of Texas, sounding like Slim Pickens trying not to be heard in the next room. While he and Ruscha traded jokes and memories, and speculated about art, I could hear behind Hickey’s comments echoes of his thinking in The Invisible Dragon, where he deconstructs the history of Western art in order to argue that beauty isn’t meretricious ornament but art’s lingua franca.

Art, he claims, is essential to the way we find order and belonging in the diversity and chaos of an open society. You buy a good drawing or lithograph and let it reorder a certain space in your house and your mind in exactly the way you vote for political leaders and give them permission to set boundaries for your life. Though Hickey sounds as if he’s being outrageous when he compares these bottom-up rules of the American republic to the practices of masochism—as opposed to the top-down order that began to creep into art institutions throughout the modern and postmodern era—he’s actually revealing his incredible skills at pattern recognition. No one commands us to vote or buy art. Like good masochists, in the voting booths, we submit to the authority we choose, willingly. The same willing submission applies when we choose between Kanye West and Wilco, or Warhol and Stella. When certain institutions try to dictate what art is “good for us,” as if viewing an installation were the equivalent of eating your peas, then something essential to both art and democracy gets lost. The free market is the ultimate crucible for lasting artistic achievement and beauty is what makes a vibrant art market thrive. For Hickey, beauty came to be viewed—in the eyes of the “therapeutic institution,” as he refers to large parts of the art world—as simply an artist’s corrupt bid to sell work, while “serious” work defies all the rules of attraction and becomes something you look at because someone who supposedly knows better than you has told you it’s good for you. Loving it isn’t required. And neither is a free market where people buy what they actually want, not what they’re supposed to want.

His examination of Mapplethorpe’s imagery is astonishingly persuasive on this score: the formal beauty of the photographer’s startling images, he says, is simply a subversive delivery system for insights having to do with art, art history, love, trust, power, and so on. (Exactly the sort of thing Brueghel, for example, did in his great political paintings.) The work beckons and shocks, but more importantly, it immediately persuades and seduces the viewer with its beauty. If it instructs or illuminates, it does so subliminally—and secondarily. The interpretations come and go. The beauty and power of the image endures. By the end of the book he convincingly argues that all great art operates this way: the excellence of what it physically embodies outlives whatever it appears to denote. How it looks, in a way, matters more than what you happen to think it means. If it’s great, its meaning may fade, yet it’s beauty—you almost want to revive the Greek term arete as a substitute for beauty—is timeless, giving each generation of viewers a chance to derive new and vital relationships to it by delving into its essential mystery in fresh ways.

In his talk with Hickey, Ed Ruscha, elaborated on this line of thinking: “This whole notion of artistic license opens up art. I feel comfortable in a vocation where I don’t have to explain things,” Ruscha said. “When you build a house, all those nails have to go in the right place. In a symphony all the notes have to go in the right place. But in art you can put the nails all on top of one another. I’m in a world where incoherence is actually a virtue. I’ve always felt lucky not having to explain myself.”

Hickey broke in: “He’s not sitting around worrying about it. He’s like my dog Ralph. He’s going after the pet food. I don’t know anything about Ed Ruscha’s work. Ed knows the sort of experience I enjoy, that’s all. We presume that we’re supposed to look at a work of art and our job is to figure it out,” Hickey said. “This is a recent phenomenon. I remember looking at my first De Kooning and it didn’t occur to me to figure it out. It occurred to me to want to see more De Koonings.”

In a way, Hickey’s love for music defines his love for art. Tumbling Dice will never get old, and that ever-fresh quality defies explanation. Hickey’s genius lies in realigning our focus on the art itself, away from interpretations, justifications, and analysis, and back in the direction of beauty’s elusive mystery and power.

“As long as a work is mysterious it stays on the wall. When I get it, it’s had it. It comes down. I don’t need something I understand on the wall. I’d divorce my wife, if I understood her. All I demand of a painting is non-stupid fun. I think you know what I mean.”

Comments are currently closed.