In the cut

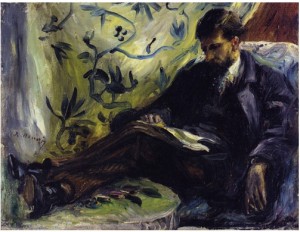

My wife and I meet our son and daughter in Palm Springs for vacation every year in August, when it’s super-cheap and affordable, and, well, broiling hot. Don’t challenge me on this. We love it. It’s a dry heat, as Bill Paxton said in Aliens. We were there again last week—golf, golf, golf, cicadas, scurrying quail, hummingbirds sometimes thick as insects on the front nine, doves, mockingbirds, roadrunners, moonlit mountains, Corona in bottles, gin and tonic, swimming, running in 95 degree heat, cards, epic dinner conversations, and drives to the Palm Desert Apple Store for a new trackpad. On top of all that, I finally visited the Palm Springs Art Museum. I went to see what I thought was a late Manet in their permanent collection, since I’d seen it in a promotion on our visit a year earlier, and it was there, all right—a gem, larger than I thought, all vigorous brushwork, the fearless shorthand execution of a master who knew he would soon die. I discovered, though, that it was part of an anonymous private collection on loan every summer, when the owner flew to cooler climes. Nice trade of services: you guard my paintings from thieves, heat and humidity, and I’ll let you show them to the public, but only if you don’t let anyone take pictures. Doh! It was a dazzling assembly of work, and I tried like hell to pilfer a few images with my iPhone, but the guards were sharp and vigilant. (My son-in-law, John, actually acted as my wingman and wandered off to see if the guard wouldn’t follow him, giving me the privacy to steal a few shots, but no dice. Though I was disappointed that he kept an eye on me, the guard was obliging enough to tell me the paintings in this exhibition were all owned by one local collector, who wanted anonymity, no doubt to protect his paintings.) In total, the room reminded me of a much smaller version of the Duncan Phillips Collection in Washington. It was a selection that showed the collector’s unerring ability to spot tremendous Modernist work: Van Gogh, an early Matisse, a whole series of Picasso drawings, three Joan Mitchells, a Rothko, a little Renoir portrait sketch more intriguing than most of the standard Renoir  fare I’ve seen over the years, a tremendous, placid non-figurative De Kooning, the Manet, and what turned out to be a small revelation for me: a set of a half-dozen Thiebauds. They were all a lesson in how to paint irresistible images, yet one of them was astonishing.

fare I’ve seen over the years, a tremendous, placid non-figurative De Kooning, the Manet, and what turned out to be a small revelation for me: a set of a half-dozen Thiebauds. They were all a lesson in how to paint irresistible images, yet one of them was astonishing.

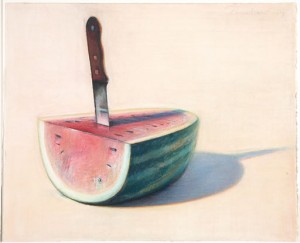

It occurs to me that I’ve been giving Thiebaud a lot of big ups, almost despite myself, because as much as I admire him, and love the late-career landscapes, there isn’t any single image of his that has knocked me out me the way this painting did. It’s an oil on panel of a wedge of watermelon impaled by a large cutting knife. I found another version of the subject online—not the same painting—and it’s not nearly as good. The photograph doesn’t even come close to conveying the saturation of his color in the Palm Springs painting, the depth of thickly applied oil that seemed to soak up the light and give you a rich tone from under the pa int’s surface, somehow. The knife had the shine of reflected light, and yet, at the same time, also had the flat abstract quality of Thiebaud’s typical work. The wooden handle was a marvel, and overall, the knife itself had an almost Arthurian sword-in-the-stone aura. The watermelon’s red fruit seemed polished and honed at the edge, with a neat semi-circle of seeds sown regularly just inside the rind, a couple strays having fallen to the surface below. And the shadow’s deep blue depths seemed to pull against the electric green of the fruit’s surface. The image he created resonated with all the pleasure of the man’s good cheer—as a viewer, you taste his subjects more than you simply see them—yet there’s an uncharacteristic implication of violence and even sex in this one. The color, the shine of the knife blade, the imagery of stabbing, the physical heaviness of what he shows you—the blade looks anchored firmly enough to quiver if you plucked it—it commands your attention with unusual authority, and yet all of these implications are bathed in his brilliant light and deeply saturated color, so that the effervescent quality of Thiebaud’s vision only seemed intensified by this mortal-seeming wound, inflicted for the sake of a summer dessert. Enjoy the sugar of those thirst-quenching bites, he seemed to be saying, and enjoy them all the more because that ominous knife casts a little strip of purple shadow down the center of the fruit. This unusual touch of duende, ultimately, seemed an almost ironic, serene reflection on a fate Thiebaud seems to have deferred indefinitely, now that he’s in his 90s.

int’s surface, somehow. The knife had the shine of reflected light, and yet, at the same time, also had the flat abstract quality of Thiebaud’s typical work. The wooden handle was a marvel, and overall, the knife itself had an almost Arthurian sword-in-the-stone aura. The watermelon’s red fruit seemed polished and honed at the edge, with a neat semi-circle of seeds sown regularly just inside the rind, a couple strays having fallen to the surface below. And the shadow’s deep blue depths seemed to pull against the electric green of the fruit’s surface. The image he created resonated with all the pleasure of the man’s good cheer—as a viewer, you taste his subjects more than you simply see them—yet there’s an uncharacteristic implication of violence and even sex in this one. The color, the shine of the knife blade, the imagery of stabbing, the physical heaviness of what he shows you—the blade looks anchored firmly enough to quiver if you plucked it—it commands your attention with unusual authority, and yet all of these implications are bathed in his brilliant light and deeply saturated color, so that the effervescent quality of Thiebaud’s vision only seemed intensified by this mortal-seeming wound, inflicted for the sake of a summer dessert. Enjoy the sugar of those thirst-quenching bites, he seemed to be saying, and enjoy them all the more because that ominous knife casts a little strip of purple shadow down the center of the fruit. This unusual touch of duende, ultimately, seemed an almost ironic, serene reflection on a fate Thiebaud seems to have deferred indefinitely, now that he’s in his 90s.

Comments are currently closed.