“It’s all prime.”

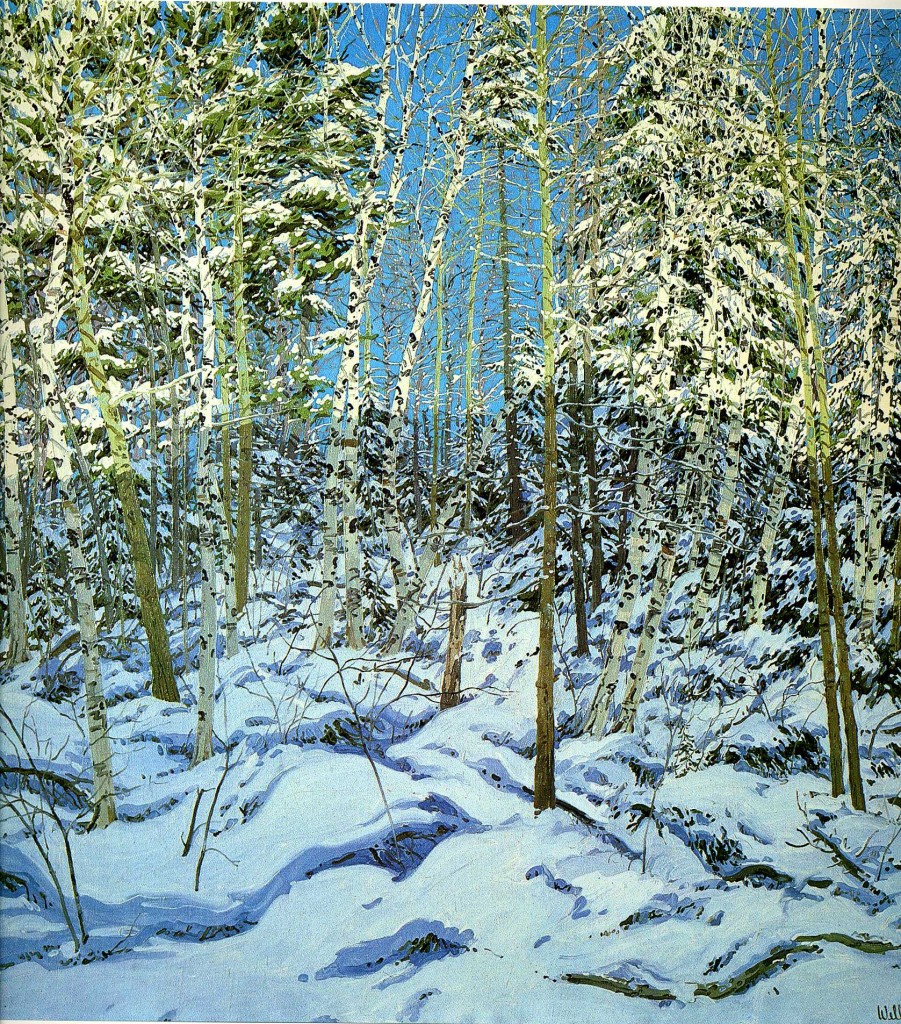

I’m still meaning to write at more length about the current show at the National Academy Museum, and how it gave me a first glimpse, after all these years, of work by Neil Welliver, Stanley Lewis, and Albert Kresch, as well as Paul Resica, whose beautiful work I’d seen here in Rochester, and three other related post-war artists. But seeing Welliver’s huge landscapes for the first time reminded me of two fairly extensive interviews he did in the 80s, much of which I’m going to reproduce here, in a couple posts, which is probably in violation of fair use. The books appear to be out of print, and often priced more expensively than most people would be willing to pay, so if there are any copyright issues, they won’t have much of an economic impact. (Represent ain’t Napster.) I haven’t made a penny off this blog for the two years I’ve been writing it, so I think I could be forgiven for passing along Welliver’s thoughts to the few people paying any attention. Plus, these coffee table books are valuable primarily for the great color reproductions of paintings as well as photographs of artists at work in their studios—and you’ll have to resort to Amazon for that. The books Art of the Real, edited by Mark Strand, and Realists at Work, by John Arthur, were both published in 1983, and I bought them a few years later. If you’re a representational painter, they’re indispensable books. I’ve returned to them repeatedly over the years for inspiration and to reread the interviews with Neil Welliver which had as strong an impact on me as his paintings did when I discovered these books. In these pages, for the first time, I set eyes on work by William Bailey, Janet Fish, Louisa Mattiasdottir, Lennart Anderson, Ralph Goings and William Beckman: a world of possibilities and a treasure of information and insight back when I was just settling down and trying to get my bearings as a painter after many years of doing whatever I felt like doing at the time, a tendency I haven’t completely lost. (I’m a slow learner.)

This past week, I returned to the interviews with Welliver in both books and was just as impressed with some of his pronouncements about his work and about painting, which strike me as profoundly truthful. He took himself very seriously. He was also capable of saying, without irony, “I was making some sensational abstract pictures at the time.” And I doubt that he meant sensational in a self-deprecating, tabloid sense of the word. I ate all this stuff up from Welliver when I was younger, though now it sounds to me as if he occasionally got just a little carried away with assumptions about painting that aren’t borne out in his work, and sometimes I wonder if he was purposely blowing smoke, testing his questioner to see if he’d be challenged on some of his self-contradictions. Anyway, he’s a fascinating character and a masterful painter, whose greatest technical strength was how far he could simplify the application of paint. You can smell the pines on the breeze and feel the sun on your face while standing inside one of his paintings—that’s pretty much what it’s like—despite how radically Welliver eliminated most of what he saw, cutting out most detail and variation in hue and value within discreetly defined flat areas of color. I wonder if his paintings couldn’t be re-done as serigraphs without losing much of their impact. That’s remarkable. These huge paintings took only a month to complete: he found a way to exert the least effort while getting the greatest impact, which is what a mastery of painting ultimately comes down to, doesn’t it? He mentions Alex Katz in both interviews, and their work seems incredibly divergent to me, and yet they have one fundamental quality in common: a fanatical simplification of method. No scumbling! No glazing! No going back over! It’s all prime! I hear Welliver shouting these things to me in my head all the time, as I glaze, and go back over, and smear and unprime everything, as it were, doing whatever it takes to make the patient start breathing again . . . but sometimes the paintings do just flow off the end of the brush, starting in one corner and working my way to the opposite one, in a way Fairfield Porter told Welliver just wasn’t possible, and when I get to the bottom corner, it’s just done. Welliver smiles.

In the early 80s, he was already generating his own electricity with a windmill on land he owned along a back road in Maine. He heated his house with wood and grew much of his own produce in a large organic garden. He resided in an 18th century farmhouse which had been taken apart at its original location and reconstructed on his property. He converted a barn into a studio. He had a skylight made from one of 10,000 sheets of glass removed from the John Hancock Tower in Boston when they began falling off the building onto the streets below.

When he started out he worked in advertising, taught in public schools. He studied painting with Albers who told him his work at the time was awful, but he saw something worthwhile in the effort and took him on. He painted farm tractors, then did totally abstract color-field paintings. Albers was friendly toward the tractors, hated the abstracts, but offered Welliver a job teaching with him. He had a chance to show the abstracts but “I thought if I got caught in the gallery network, development would end. I was going to go my own way or I wasn’t and it was a direction other than where the art world was going.”

He tried a lot of different things for two years and was miserable. Some things he liked emerged in paintings. “My vision had been rural—I grew up in Pennsylvania in an environment that was unspoiled country woods and so on—and that vision slowly took over the paintings . . .”

Finally he showed his work The Stable, a hot gallery at the time in New York City, and then left for Asia for most of a year before returning to the U.S. He journeyed to Canada, but didn’t speak French well enough to stay there comfortably, and so he worked his way down the coast until he ended up in Maine where he stayed. He headed inland and found a house and land on a back road. He stayed there from then on.

Here are quotes from the John Arthur interview, with my thoughts and reactions, where I can’t resist, which is most of the time:

I never forced a model to sit out during black fly season. <<< He painted models standing naked in very cold streams. I wonder if any other artist in history has made this claim about kindness to models.>>>

I sure as hell don’t object to (working from photographs). I see some work that’s done from photographs that interests me greatly, but photographs are monocular. They exclude by nature of the machine the psychology of the picture, which I’m interested in—the binocularity of things—so I’ve never used photos. <<<He beat Hockney to it. Unless one can paint in 3D or one is a Cubist, the binocularity of things is always reduced to the monocular, in a painting. There is, after all, only one image that greets both eyes in the end result, right? The whole act of representational painting is a way of reducing the “binocularity of things” to a monocular view. So . . . >>>

I can hardly read the photographs, so to speak. <<<It all depends on the photographs.>>

I met Fairfield Porter in 1958. I liked him well enough but was not very interested in his work. I thought it French and soft. In short, I missed it. I later told Fairfield I had missed his painting and thought it just French painting. Fairfield said when he had first seen my work he thought it “just good-natured Expressionism.” We rarely talked about painting. He came out of . . . French painting and I came out of American abstract painting. So we approached painting in a very different way. He came here once and saw a painting half finished. He just said, “That can’t be done. You simply can’t do that.” Then he said, “We’re antithetical. You use your mind one way; I use mine another. I recognize what you’re doing, but I can’t imagine it.”

I think that the Fairfield Porter paintings that are good are very very good American paintings. God knows that they can never be dismissed. I can’t imagine that. But whether Fairfield’s a major painter or a minor painter is a judgment to be taken care of by time, as it will be for all of us. Columbus Day is as good as painting gets. My generation of painters, people who come out of abstract painting or were affected greatly by Expressionism, I think we come from very different stuff and Fairfield had virtually no effect on us. He was one of the most inordinately decent people I’ve ever met. <<<Welliver did have an ego. He overlooks the fact that Willem and Elaine De Kooning were Porter’s staunchest advocates and helped connect him with his first gallery, not that this negates what Welliver says. Porter took far more chances than Welliver and succeeded and failed based on the risks his took, while Welliver learned how to do what he did and did it over and over. He kept his choices (and colors) within a much narrower range and turned out paintings that in some ways are all the same, in the way that one Rothko is the same as another.>>>

Jay Yang said to me once, “Everything (Welliver did) was painted with the same touch and the same intensity.”<<<This is absolutely true and is Welliver’s greatest strength. >>>

For me the energy in a representational painting flows on two levels, and for many painters I think it doesn’t. One level is the material and the canvas. Sometimes whole sets of relationships and “energy flows” take place on that level, and whether you see the image or not is immaterial. Then there’s another level of observations of objects and space—natural associations. The simultaneous presence of those two aspects of the painting is what I’m interested in. <<<Eternal wisdom. The truth of painting.>>>

I remember one time Paul Resika was here and I showed him a brook that is a sea of boulders. He walked in and said, “A feast of planes.” For me there were no planes at all. Instead, I was seeing a great energy flow of light, fragments of light whistling along a brook and back through the total volume we were looking into. The idea of immediately focusing on the object and its planes—I wasn’t seeing that at all. I was looking at something extremely obscure, not light in the normal sense, light bathing objects, but light in the air, flashing and moving like a flow of energy through space. That interests me greatly. That’s what my paintings are about. <<Precisely what Porter’s paintings were about as well. The energy of the whole, in which objects are just fragments of the whole he’s trying to convey, just elements of the “volume” Welliver is talking about. Also, this contradicts in some ways Welliver’s assertion that he is interested in the extreme particularity of one tree vs. another tree and one particular place vs. any other place. He quotes Carlos Castaneda about the energy of certain places, and yet his technique suggests that none of this is the case. He painted nearly everything with the same kind of method and his images depend on an energy and sense of light that’s evenly distributed across the canvas: almost any place would do. He’s painting the light and the wholeness of the moment, not the individual objects.>>>

(The Hudson River School) were totally involved with the specific characteristics of a situation, and I’m much more interested in the general energy flow through space.

We’re a meager lot and don’t deserve the dominance we certainly have on this earth.

I use eight colors. I use Permalba white because I like its consistency, ivory black, cadmium red scarlet, manganese blue, ultramarine blue, lemon yellow, cadmium yellow and Talens green light. (No earth tones, mixes red green and white for gray or brown.) I’m rarely after a neutral gray, but those grays which are charged with blue or green or something.

No glazing, no scumbling.

I am still making night pictures but a transcendental one evades me.

Interesting facts from the interview:

He would carry seventy pounds of materials for painting on his treks to a site.

He worked three hours per day, for three days, on small preparatory paintings.

One of the most interesting aspects of Welliver’s technique is that he would take a smaller drawing or painting done en plein air and then replicate it with charcoal on a very large sheet of sign painter’s paper. He didn’t use any markers for composition, just drawing directly with little going back, very accurately. Then he would take the paper, perforate it along the lines he’d drawn and then transfer the charcoal through the holes onto the canvas. He said he did this to avoid the tedium which would be involved in the larger drawing: he didn’t want a trace of that tedium to be present in the guide lines on the canvas itself. It’s almost superstitious, but I totally understand it. The act of painting is full of these little OCD-like habits, like routines a batter goes through at home plate, preparing for a pitch. He would use a perforating wheel to puncture the large paper and a pounce bag for transferring the drawing. Also, he would work on a palette encrusted with old paint, rather than on a white clean surface. He liked to see the new paint in relation to the other colors he’d been using in the past: a perfect lesson from Albers about how color only becomes what it is in relation to other colors around it.

He worked from ten to five daily in the studio. A painting would take only four to five weeks to complete.

I’ll follow this up, eventually with selections from the interview with Mark Strand.

Comments are currently closed.