Dancing about architecture

AVC: By the way, did you really coin the expression “writing about music is like dancing about architecture,” as has been suggested on occasion?

Martin Mull: You know, I believe I had heard that as an apocryphal story, that “talking about art is like dancing about architecture.” Apparently, it had happened at a lecture at Pratt Institute, in New York.

Herewith, another little dance about architecture. In a previous post, I quoted a passage about the British philosopher Iris Murdoch from a book by another author, Matthew Crawford:

Iris Murdoch writes that to respond to the world justly, you first have to perceive it clearly, and this requires a kind of “unselfing.” “Anything which alters consciousness in the direction of unselfishness, objectivity and realism is to be connected with virtue.” “Virtue is the attempt to pierce the veil of selfish consciousness and join the world as it really is.” This attempt is never fully successful, because we are preoccupied with our own concerns. But getting outside her own head is the task the artist sets herself . . .

I’ve been thinking about it again, while writing recently about the way I paint and how diligently Tim Jenison worked to create a painting equal to Vermeer’s work. These lines of thought came together in the notion that for a representational artist, art is largely a matter of copying: mimesis. To make a charcoal line on paper come alive as a tiger or a gun or a flower is to submit to the ordeal of copying what’s already the case in the world. My post on Vermeer addressed how Vermeer copied what he saw as effectively as any painter who ever lived, but he also did more than copy, by ordering what he saw and undoubtedly altering it, in paint, to unify his vision. But copying was, by and large, the mission. To labor for long periods of time at the job of copying is the drudgery but also the joy of being a painter.

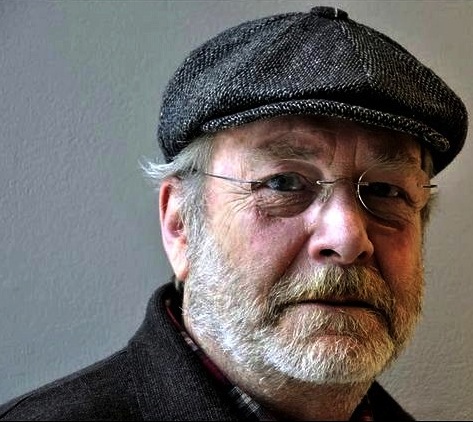

All of these thoughts returned, again, while I listened to Martin Mull talk, during a long interview, about his own work as an artist. He achieved a rare level of fame, decades ago, as a comedian and actor, became friends with people like Steve Martin and a close collaborator with Fred Willard, whose career as an actor has flourished in the years since. Mull’s profile has gotten much less visible, as he appears to have focused his energy on painting rather than performing. His work is fascinating, and beautifully crafted, though at first it struck me that he was pushing his work a few ratchets too far toward postmodern cool. But the more I listened to him talk about the work, and about his own attitude toward himself, the more I warmed up to his assembled glimpses of suburban life that seem drained of emotion and meaning and context: little peeks into the mind of some shut-in who’s too depressed to make sense of why pretty Mrs. Brooks next door happens to be outside, standing naked on her diving board. After a while you feel, I get the point: middle-class American life can come to seem pretty empty. (If contemporary was the world of the 60s, since he draws largely from collections of scrapbook photography collected by people he doesn’t know.) Yet the craft and concentration he devotes to his work strike me as more significant than how he designs his images.

Mull, who earned a degree from the Rhode Island School of Design, describes his work in the interview:

Show business is fun because it’s working with other people. Painting, it’s your ass alone on the cross. You get all the credit and all the blame. It’s something I’ve been pursuing actively for 64 years, since I was three.

These are all 9 x 9 oil paintings done on board. I work from collages I make using 1960s nudist magazines. It was the mother lode if you were a 12-year-old boy. My god, look what I’ve found! I paste them up using two or three different things. I love the idiot process of painting photo-realistic images of the collages. I’ve never used a computer. I can’t do anything modern-day. (I use disposable cameras you buy at the drug store, for my own shots). When I was doing the four seasons, I was combining two seasons in one. In L.A. where there are no seasons. These are 50 x 70 inches all oil on linen. This is some house near the airport. This is “Summer.” This is “Fall.” (It shows a nude woman superimposed on a 60s ranch house.) I keep doing these series that have been done to death. The Four Seasons. The Seven Deadly Sins. That’s Envy. Steve Martin owns that. He described the whole series as oblique. I wanted to take the seven deadly sins and put them into the most ordinary setting. Things we do every day.

In that series, lust is represented in a black and white shot completely devoid of eroticism: an older couple sitting side by side on a beach. It got interesting when Mull described how he has worked recently from family photographs taken by people he’s never met.

My wife, who is computer literate, was surfing around and found that there are people selling off their family photos on eBay. You can get Marge and George Rogers from Topeka, showing when they we went to Niagara Falls. People sell them 200 pictures in a box. I’ll get a stack of a hundred of them. And I’ll go through them until it’s Oh My God. These are pieced together from the Oh My Gods. It’s so voyeuristic.

At this point, I was ready to click to another interview. The emotionless irony, the stance of looking down at another family from a superior intellectual prospect, high overhead, strikes me as a one of the foundations of modernism, and almost the cold heart of postmodern work. In other words, nothing here for me. But I kept listening and started to like him precisely because of how he seems himself less as a philosopher passing judgment on happiness, American-style, and more of a diligent workman, a tradesman applying his skills to a task that has its own worth regardless of what it “means.”

He takes his purchased photographs and combines parts of them, by hand, not on a computer—there’s no Photoshop or Illustrator involved—apparently just the old school reliance on scissors and glue. Once he has created a new hybrid image by hand, he copies it slowly and painstakingly in paint. There’s no larger purpose than to create a haunting image and turn it into paint. Whatever a viewer sees in the image comes as much from the viewer as from Mull’s conscious intent.

It allows you as a painter to be, not a pure painter, but there’s a lot of nuts and boltedness in getting things right. It lets you objectify what you’re doing. I have no idea if these people are dead or alive, and it allows me to invent a narrative as I’m doing it. It grows in the doing. It’s like Chartres, the guy who put in the footers and the gargoyles. It isn’t “I’m a sculptor.” It’s “I work with stone.”

He gets up at 5 a.m. and gets to work. It’s a relief not to have to please anyone else and simply lose himself in the task at hand of paying attention to what’s there and making an image of it in paint. In his days as a comic, which you can sample on YouTube, he appeared to be utterly relaxed, natural and spontaneous, and very funny, yet he’s happy to leave all of that behind.

I don’t feel the need to get up in front of people and be funny now.

Comments are currently closed.