Multiplicity

A fantastic show of work from 13 contemporary Japanese artists, at the Memorial Art Gallery, stuck me as a thrilling demonstration of how an obsessive focus on something as impersonal as method can generate original, idiosyncratic work that’s emotionally powerful and wonderfully expressive. I’ve been working on work for a small solo show in June at Viridian Artists, built loosely and maybe a bit whimsically around the idea of polarity, so I was primed to be dazzled by what I saw here. All the work here levitates in the mind, lofted by the magnetic poles of opposing forces: the abstract work hints beautifully at representation and the most representational work hews faithfully to narrow formal constraints. The rigor of technique disciplines, unobstreperously and almost politely, intense personal passions: you can feel the Japanese adherence to self-effacement in the strictures these artists have applied to what they do, and yet, at the same time, these self-imposed boundaries seem to heighten the passion. It’s like watching The Age of Innocence, start to finish, in a single glance. What you end up with is highly refined mastery, and remarkably some of these artists appear to be only a few years into their careers.

Curated by Sam Yates, of the Ewing Gallery of Art and Architecture, with a grant from the University of Tennessee, the show features work based on the idea of multiple images created from a master: it’s a show about how this multiple-master process in printmaking has evolved into various forms, including three-dimensional installations. The show’s catalog offers a concise history of printmaking in Japan, beginning in 1603 with woodblock, a century after Durer was making a living with woodcuts in Germany. It reminds you that, beginning in 1867, imported Japanese woodcuts had an enormous effect on European art, just as it was getting modern in France. Van Gogh never would have arrived at his mature style without his eyes having been opened when he saw the flattened imagery of prints from Hiroshige and Hokusai being shown in Paris. It’s easy to see how profoundly he was affected by them: it enabled him, in part, to quit trying to be yet another Impressionist and finally be himself. The flatness of the image: you can follow it from these Japanese prints in Paris all the way to Clement Greenberg’s extreme insistence about how a painting is all the flat surface.

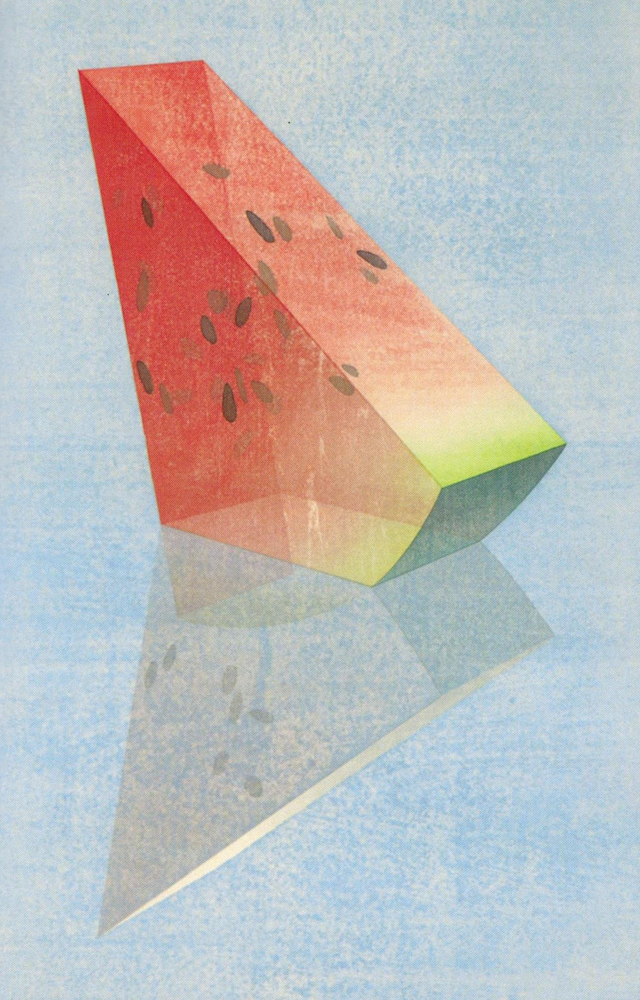

If I can, I’m going to post a series of images from these artists with a few reflections, over the next week or two. We know where good intentions often lead, though. Above is a woodblock print of a watermelon wedge, by Shoji Myamoto, that knocked me out when I saw it about a week ago. His images of food hum with restrained energy, incredibly precise, the hues perfectly registered in delicate, balanced juxtapositions. The watermelon is maybe the most representational, but he does with it what he does in his other images: takes a natural form and simplifies it into its more or less it’s ideal Platonic geometry. What was opaque becomes translucent. Was was curved turns a right corner. A mollusk can become a box in his world. What he evokes in this way would have fascinated and humbled Escher, who couldn’t have dreamt these colors. As with all of these artists, Myamoto’s statement is incredibly humble and unassuming. If we can credit the losses involved in translating Japanese thoughts into English words, then we should all be forced to stain our artist’s statements through the sieve of a second language:

I’ve been making woodcut prints using traditional Japanese techniques. The techniques add a new point of view to some familiar things that I draw. Most of themes (sic) of my works are food such as sushi and fruit. We eat many foods without thinking about them, but the color and form of food is actually interesting. And I wish to express such interest.

He’s doing so much more, but why boast. The work doesn’t need the words.

Comments are currently closed.