Meow Meow Beans and me

Today I will continue working on a painting I started more than three weeks ago, hoping to finish some challenging work I’d like to show in June at Viridian Artist. I’m so busy right now, I rarely have time to write anything thoughtful here, but when I wake up early I try–which is nearly every morning in this endless winter, with record low temperatures here in Rochester, which apparently has drifted northward to the edge of the arctic.

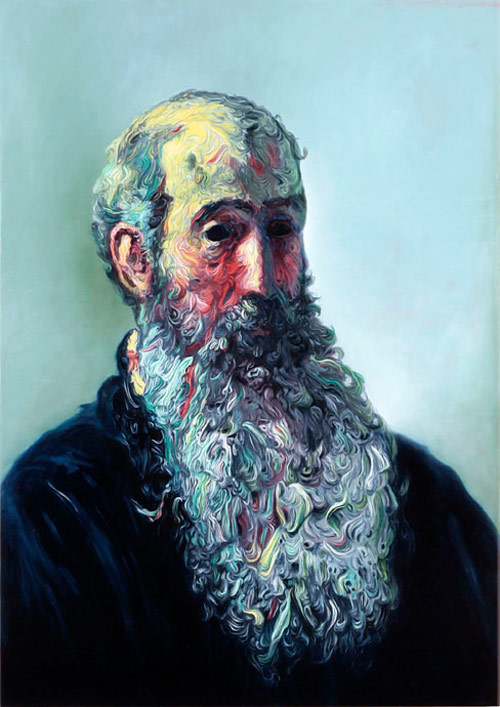

Recently, my friend Walt Thomas sent me How a Science Fiction Book Cover Became A $5.7 Million Painting. It describes an auction sale of a painting in which Glenn Brown appropriated an illustration by Chris Foss, used as the cover for a book by Isaac Asimov, and then repainted the resulting image in his own heightened style. (You can see other examples of Glenn Brown’s compelling postmodern work with a quick Google search: they’re like a re-envisioning of what the Old Masters saw through the eyes of a charismatic zombie. When he’s dealing with historical work, his own paintings are fantastic. When he’s asking permission and then slightly modifying a contemporary painter’s output, it irks me, especially when the art world uses the results to move so much money from one deep pocket to another.) If you depend that much on the work of another living artist, then shouldn’t the proceeds be split fifty/fifty? Apparently postmodernism, with its irony and appropriation, is alive and well, one of the few great jobs in this zombie economy if you can get it. Needless to say, I would never complain when DJ Premier samples, say, Illmatic, (I guess he’d be sampling himself, in a way) which itself sampled plenty of previous recordings. He would get nothing but gratitude from me, but those are fair use, in my book, little quotes from much larger work. Yet when you enlarge and essentially colorize an entire earlier image that was sold as the livelihood of another artist, isn’t that crossing the line? I do not know the answer to this question, since I’m not an attorney, but I do know that it doesn’t feel right to me, the way so much postmodern work feels, intentionally or not, inauthentic, more or less a clever con. (I don’t feel that way about Brown’s reconstruction of Old Master images in his own vision, like the self-portrait by Pissarro above. Those paintings feel original in their own way, intensely painterly and passionate and spooky, and they belong to a long tradition of internalizing previous work by repainting it in the artist’s own style. Even Van Gogh did it. In Brown’s reworking of Rembrandt, say, there’s more of Brown in the paintings than the previous artist and Brown’s own vision is intriguing.)

What troubles me about the assumptions that make this kind of work possible is something much larger in our culture—and it might even be a deeper shift than the word “culture” indicates. This feels like a steady, slow erosion of the notion of human nature itself. I’m tempted to reread The Plague, because what’s happening now feels as if that book could serve as its metaphor. It’s seems to be happening everywhere. It’s the way in which everything now seems to conspire to dissolve a sense of individual identity and selfhood, while making you believe you’re asserting it like never before. I believe this is one of the primary goals of postmodernism itself, isn’t it? We have no soul, no enduring identity; we are simply a welter of impulses, perceptions, ideas, emotions, woven together by cultural and economic forces outside our control, mere nodes in a network of signifiers that give birth to the illusion that we actually exist as individuals with an independent mind and heart, free to choose what we do in our lives. (Don’t remind me how close that is to Buddhist metaphysics, since I’ve done bush-league Buddhist meditation for decades and am an enthusiastic advocate for wisdom and compassion, as little as I might practice either in my own life. I’m on a rant here, and I don’t need inconvenient reminders like that right now.) As dutiful postmodernists, we need to deconstruct what has come before, and what’s around us, in order to become free of it, though who, pray tell, is free when it’s all said and done, if our individual identity is itself an illusion? If we are just a mechanistic net of neurons firing in sequences determined by everything happening in the world around us, conjuring up an illusion of personal integrity, then why does it matter what we do? Hence the gloomy, lucrative ouvre of Glenn Brown: rather than be troubled by the anxieties of influence when gazing at the Old Masters, just appropriate it and do some interesting violence to it, adding your signature at the bottom. And I use the word interesting without irony here. I like what he does. So, given this assumption, that many of the beliefs we inherited from the Enlightenment, and the Greeks, which went into our ostensibly naïve assumptions about how an individual can make his or her way through the world, and enabled us to found this nation of individuals who once believed they were free to build an original life for themselves out of hard work and ingenuity, well that’s all so 20th century . . . If you originated it, I can adopt and sell it. Ideas can’t be copyrighted. Information wants to be free. And so on. We aren’t really free agents, with an enduring identity that has any substance apart from the soup of signifiers around us—the shows we watch, the ads we take in, the music we hear, the noises we make on social media, such as this blog—we’re just a collection of impulses generated by what other people have done and are doing around us and who we are depends on what others know about us.

Believe this, and then all of what’s happening now makes sense. Privacy has been one of the first imperatives to go. It’s founded on the notion that we have some right to ourselves—our thoughts, our feelings, our possessions and the fruits of our labor in general–that no one else can violate. Is it proper to feel this matters now? For more than a decade—think back to your first Compuserve or AOL email account if you were alive then, back in the 90s if you want to know when this really started—your private thoughts and feelings have become more and more open to public scrutiny. “If you don’t want it on the front page, don’t put it in an email” has been an adage for email. I have friends who say, “I’m not doing anything wrong, why should I care if someone else reads my email?” And they probably shouldn’t care, but something integral to being human has been lost in the willingness to voice that dismissive question. We are becoming unreal to ourselves in a way that my friend Richard Todd explored in The Thing Itself: it gets harder and harder to distinguish between what’s illusory and what isn’t. (Not that it was ever easy in the moral realm.) If someone else is free to carefully monitor the content of my life on the Internet, is that evil or just the whole point of being on the Internet now? Along with Diane Feinstein, I lean toward the former.

Last Thursday’s Community episode did a fast, poetic twenty minutes or so on the psychological dependency of social media. A beta test of a new app, Meow Meow Beans, turned the college into a hierarchy of a small elite leisure class wearing togas and the rest of the school, the reign of the most popular over all the rest as everyone struggled to get a five-star popularity rating; it was replaced by a revolutionary junta, just a mirror image of one tyranny rather than the other. Capitalist excess followed by totalitarian tyranny, the old familiar story. The latter made more sense as a critique of social media: the mob rule of popularity ratings leading to a revolution of the people, which leads to just another kind of elitism. What it suggested to me is that people had pretty much become their phones, where they tracked what other people thought of them. No one really had any kind of character apart from how they were seen. (Leave it to a sitcom to have familiarity with the need to be seen in order to be.) The implication was that anything private left after that kind of self-exposure either didn’t matter or was a threat to the system. The implication was that as an Internet participant you are essentially saying, you don’t care if your entire life is on view to anyone and everyone, whether it’s your group of friends or your larger brother at the NSA, since you “have nothing to hide.”

Privacy isn’t simply about hiding something wrong or bad. It’s about preserving the meaning of what you do in a way that others aren’t able to understand or manipulate or deconstruct to their own ends. In the composition of a great poem, there is a level of hidden meaning, accessible only to a poet, that gives the poem power—no amount of deconstruction will uncover what that is, because it’s private. It denotes all sorts of things, but ultimately what drives it, what keeps a poem fresh, I believe, is the mystery of what isn’t there, a mystery otherwise known as Robert Frost or Syliva Plath or T.S. Eliot. Someone else could sample that poem and put it to other uses, and dissect it to within an inch of its life, but what others can’t sample is the essence, the heart, of the work itself. What keeps it alive is the elusive identity of the poet, there between every word, but also not there in what’s actually said. It’s something you can observe up to a point, and even imitate how it expresses itself, but it’s ultimately beyond reach. What a person actually is can’t be digitized or politicized or channelled into some intellectual agenda. We seem to think nothing we do or think or experience should be beyond reach now: we live in order to exhibit who what when where and how we are. We’re willing participants in the exposure of of our lives. As well as, secondarily, to publish cat videos. (A gross overstatement, considering the almost entirely trivial content of social media.) Thursday’s episode of Community satirized this impulse. A new app put everyone at the mercy of his or her cell phone, everyone doing anything they could to get a five-star Meow Meow Beans rating. It was a lot to weight to pack into a half-hour sitcom, but Dan Harmon made it entertaining (I’m assuming he’s still in charge at the show). It will be interesting to see if “Meow Meow Beans” becomes a meme on social media.

Few people seem to care about privacy now. Is property, as well, starting to follow down the same path? I once bought albums on vinyl, and movies on videotape. I once owned Photoshop. Now I’m wondering if I shouldn’t just give up ownership outright and rent access to all my entertainment and art and software via some kind of streaming account, such as Spotify. I still own a car, but fewer and fewer people do. In this economy isn’t it smarter to rent? Will access to all information, and property, follow this same path? (Did the loss of net neutrality get much notice in the media?) I have always had to pay for my New York Times. Nothing wrong with that. But I used to actually own it, and have private access to it whenever I wanted, as long as I was willing to hoard towers of newspapers in a corner. I much prefer being able to search the archive of that newspaper’s history on the Web. But what I give up is control of my access to that information. If someone turns off the Internet spigot, then I am haplessly uninformed. And, granted I’m getting older, and memory is slowly being revealed as the unreliable narrator of my life, but why should I care if I can’t remember anything? I’ve outsourced my memory in large part to my iPhone and my laptop. Google is my memory now. At some point if an individual’s link to the Internet gets severed, could that be the equivalent to a computer reboot? Tabula rasa, reformat, reinstall. We start fresh, our brains merely blank slates we can refill with our operating system when our ISP grants us access again to our thoughts and dreams. Life continues to feel more and more, as it has been doing for years now, like a Philip Dick novel.

We’re being trained to think of experience as something granted by an external source: our ISP, our cable provider. Streaming vs. owning is an example of this paradigm shift, but you can see it in everything. The loss of privacy is enormous in the way it shapes the concept of a lone, private, Thoreauvian self—as something either inconsequential or illusory—and nobody seems to really care that much about it, because we’re all too distracted by the endless incoming torrent of media to actually notice how we’ve simply become another outgoing stream of data. Once you do away with that individual agenthood, then you’ve made the whole notion of America obsolete. If there are no self-sustaining individuals, then what’s the point of that antiquated Constitution?

Should I bring this around to painting now, or just keep getting things off my chest?

Painting strikes me as one of the most utterly Luddite things one can do at this point. I sit at my old-school easel, with a smelly assortment of minerals and fluids on a sheet of thick glass, with wooly, worn brushes I struggle to smooth into a pointed tip, and I spend hours applying color, inch by inch, slowly, to a length of cloth stapled to a wooden frame. The physical struggle of painting is a large part of what it’s about. As I’m sure I’ve pointed out before, a whole length of muscles on one side of my back are far more developed than the muscles on the other side, from decades of simply holding a nearly weightless brush up in the air. When I saw it in a mirror a few years ago I thought, what the hell?, and eventually realized, oh right, I’m a painter.

In physical terms painting is like the sort of labor that robots have stolen from us. Yet in all other respects, it’s exactly the opposite of it. It’s a unique embodiment of who I am, as a person, an individual, partly because it can’t be reduced to data. It’s one of the few creative acts left that can’t be copied exactly as it is. It’s one-off, and in that lies the pathos and beauty and real-ness of it. Yes, it can be photographed and passed around in extremely hi-res images that show me every last detail of the surface, but in all the years of making and looking at art, I’ve yet to see a photographic image that actually conveys what I see when I look at the actual work. It may have to do with the way oil paint reflects light, as skin does, from various depths: the outer surface, the deeper layers of flesh, and even the dark course of veins, all reflecting different colors that mix on the retina in a way that a flat reproduction can’t. It averages out those colors into a single one, flattening the image and giving you the next best thing. But there’s so much more to it than that single color per pixel. If lit a certain way for the shot, a photograph can even show you the texture of the surface. I know from reproductions that Braque mixed sand into his paint, but no photograph of his work can convey the sense that, when you see one of his gueridons at the Phillips, you are looking at something as solid and heavy and ancient as a sheet of sandstone, where the colors are merely striations in the rock itself. As is true of Burchfield, Braque conveys something utterly unique in his best paintings, something no other painter has even remotely achieved, and I’ll be damned if I can say what exactly that is, but I love that quality in their work the way I love sunlight. You can’t get it from a photograph of what Braque did: you can get a taste, but it isn’t the same. Bonnard, don’t get me started. There’s no way to grasp what Bonnard achieved through reproductions of his work. You have to see the actual paintings. Vuillard as well. I could add dozens of other names. But what if someone, with a 3D printer, could actually recreate a three-dimensional duplicate of one of Braque’s paintings? That way you would have everything: the color, the texture, the relief map of the painted surface itself. But wouldn’t it be colored plastic? A 3D printer that could generate objects out of the original materials? Are we into the realm of absurdity here? (On the other hand, if someone could do that, I’d hang it on my wall. I can’t afford the real thing.)

My point is that painting is one of the ways we have of being true to the mystery, the secrecy, of human nature. It’s a stubborn way of living off the grid, at least in the act of making it. With the ongoing death of art galleries (OK Harris, R.I.P.), the rise of the Internet as a marketplace for art, and all the other ways we can addle our minds media—here I am using that media, right?—our culture is attempting to deny the reality of what painting embodies, as may be eroding the privacy and mystery and integrity of individual human nature. One way of standing in opposition to that resides in a willingness to quit ranting and just get back to the labor of picking up a paint brush, which, finally, I intend to do right now. Or as someone ought to have said on Community, “Be a one, and be yourself.” Maybe someone did. If I missed it, it was probably because I was checking email.

Comments are currently closed.