A requiem of water

At first almost against my will, I turned on the coverage of the 9/11 anniversary memorial ceremony. It has been so hyped by the media for days that I felt I’d had enough. Yet it’s on and I can’t turn it off: understated, beautiful and moving. I’d seen one of the bag-pipers on the street in Chelsea only a few days ago without understanding who he was: thick red tartan kilt, knee-high woolen socks, tugging a little wheeled carry-on suitcase behind him, probably trying to locate his hotel room. But that was as close as I got to the site, because the city had asked everyone to stay away from the scene. It’s a sustained, disciplined exercise in sorrow. The songs by James Taylor and Paul Simon, the moments of silence, the tolling of the little bell, a son getting up to the microphone to tell his father how much he still misses him after ten years . . . it couldn’t have been more effectively orchestrated.

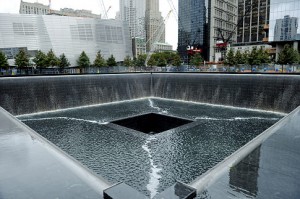

Yet what struck me more than anything this morning was the power of the two memorial pools. If someone is searching for evidence to show the value of conceptual art—and I’ve always had a hard time finding it—these two pools stand as proof that work created from the blueprint of an idea can be brilliant, effective, and mysteriously powerful. These two pools work for many of the reasons Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial works, because the artist’s humble self-effacement answers perfectly to the work’s historical and artistic needs. The two pools preserve the footprint of the twin towers, and by transforming these pits into waterfalls, they create images which seem to be the exact physical opposite of a public fountain. They are whirlpools that don’t whirl but simply surrender to gravity. Fountains, with their collection of tossed pennies, represent beginnings and the future: they spring upward in ways symbolic of life’s origins and all the hope that your wishes will come true. The 9/11 memorial pools speak of the past, not the future, and remind you of your own mortality in a way that’s both tranquil and deeply disturbing. Against the image of a round pool gathering its water into a central spout, defying gravity, these square pools show a quadrangle of water falling, flowing and then draining into an ominous, disquieting tunnel—all the water falls into the earth at the basin’s center where, in a fountain, it would be shooting up to heaven. And the water flows into central pits that look as if they could very well be bottomless—the falling never seems to end here. What’s amazing is that gazing down into what is effectively the antithesis of a tall building, you have a twinge of vertigo, as if you’re standing on top of one—and thus it brings you back, imaginatively, to the top of the towers that have disappeared. If you needed to invent a Chinese ideogram, a new word rendered as a picture, which stands for the notion of free-fall, emptiness, loss, and death—all major food groups for existential anxiety combined into one unified image—these two pools would be that visual word. Like Maya Lin’s classic work, the greatness of this memorial resides in what’s missing, in how the memorial itself almost isn’t even there.

Comments are currently closed.