Make it timeless, not new

I was browsing through the squibs in the front of the most recent The New Yorker fresh from my mailbox, hoping to find something to see on a quick trip to Manhattan where Nancy and I, along with a couple friends, have tickets for the Matisse show at MoMA. I spotted three things that stood out, not for what they were critiquing, but for the thoughts expressed in these A.D.D.-friendly five-sentence reviews. Here they are:

1. Museum of Modern Art: “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in the Forever Now.”

“The ruling insight that the thoughtful curator Laura Hoptman proposes and the artists confirm is that anything attempted in painting now can’t help but be a do-over of something from the past, unless it’s so nugatory that nobody before thought to bother with it.”

(But my first response to this was: I will see your nugatory and raise you a negatory. Yes, history has run its course for visual art. The notion of progress is dead. But I have some humble qualifications that fly in the face of what I this show’s apparent tone and spirit. More below.)

I turned the page and found my counterpoint already put into words:

2. Marcus Roberts

While raising money on Kickstarter for his latest project–recording a suite of music that he wrote some twenty years ago, called “Romance, Swing, and the Blues”–the pianist and composer declared that “all great jazz is modern jazz–whatever the age of the piece, we make it ‘modern’ (relevant to our own time in history) when we play it.” This multi-stylistic dictum informs his work with his new twelve-member band, Modern Jazz Generation, which recently released a double album of the material.

(Obviously, right? The individual performer makes it new. Anyone who has heard a great cover knows this.)

3. “The Contract”

In the European Union, artists receive a royalty each time their works are resold. The U.S. has no such droit de suite, but in 1971 the curator-dealer Seith Siegelaub drafted a rarely used contract to guarantee artists fifteen percent of profits from future sales. The conceit of this show is that all the works in it . . . are subject to the agreement. Is this premise better suited to an article or a symposium than it is to an exhibition? Probably, but in this turbo-charged art market the show has the rare virtue of subordinating speculators’ profits to artists’ welfare. (The show, at Essex Street, was over on Jan. 11, even though this issue of The New Yorker is dated Jan. 12. Which is typical of these notices in The New Yorker: some seem to sit in the queue until after their use-by date.)

Last things first. I wish I’d seen this show just to have been in a place briefly where someone was trying to overturn some tables in the financialized temple of art. The show comments sardonically on the fusion of art and finance–it’s a funny way to nudge buyers, suggesting the work on view would be rapidly rising in value and be irresistible when faced with a chance to resell it–as well as a great idea to further enrich any living artists who aren’t already making a fortune at the art fairs by selling work purchased as a substitute for, say, oil commodities. As if anyone whose work is that hot needs a royalty from future sales . . . but still, it’s a gesture in support of creators rather than speculators. Precisely the same favoritism ought to be applied to the world of business in general, tipping the scales in favor of Wal-Mart floor workers over Wall Street bankers. But fully established artists these days are one-percenters themselves so . . .

Now, about this MoMA show. Arthur Danto announced the end of the history of art long ago, and I’ve been dutifully pointing out here that there’s nothing new under the sun in art, in the old sense of “new” as an advance in art’s scope toward greater artistic freedom and power. Anything can be art, since Duchamp and Warhol. There are no new frontiers. Get over it. We don’t need sophisticated shows at MoMA to point out the obvious. But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing new in painting, in a sense that really matters. What that “newness” actually is remains inexpressible the way that your children’s worthiness of love will remain something that doesn’t require a theory to elucidate or justify.

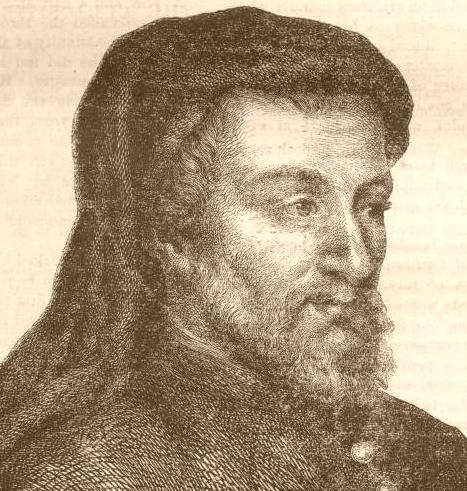

When it arrives, spring is as new as it can ever get up in these parts on the lower shore of Lake Ontario, where winter becomes a cowl of cold gray vacancy overhead that siphons the color out of everything for four months. The newness of April is exactly the newness embodied in the opening lines of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales which are so old that they are virtually incomprehensible, English has changed so much. It’s the newness of the first robin’s song in the trees once spring has arrived. That spring, and that robin, are identical, in almost all respects, to every spring and robin that have arrived here for a thousand years. And yet they are new. Absolutely the same as they ever were, but new and alive. Figure that out and you’ll know what it takes to make painting new.

It isn’t about theory, or art history, or putting an ironic spin on the Old Masters or, God help us, painting things that say Painting is Dead. The challenge is that, as art becomes more and more a matter of investing one’s whole individual being, one’s entire apprehension of life, into a painted image–having left behind the need to belong to a school or period of style of making art–there is even less and less to analyze and say about the work. This is why you have shows like this at MoMA. It gives the surrounding people something to do, now that there’s less and less to say about the act of making art. It’s about seeing, not saying. It’s an entirely interior, secret, human transaction between two people who know how to see what makes the slightest little things joyful in life, and it isn’t about money, nor about finding a market, nor about anything but this attempt to make the act of building a painting sacramental, friendly, a gesture of kindness and generosity, one person to another, or, for the lucky few, one person to a million (one at a time). Newness is a religion for marketers. What matters in painting seems to have become completely withdrawn to a region inaccessible to theorists and appraisers. But in reality it’s where it has always been, at a level where you can’t quite get to it or can’t pin it down, can’t explain exactly what it is, anymore than you can do that for life itself. But you can definitely see it. When it’s there, in the work, it’s as thrilling as the sound of a wood thrush who has gotten lost and found his way into your backyard, miles from the woods where he belongs and where few people go.

Comments are currently closed.