American tone poems

For the next three weeks, you can see a rare and brilliantly assembled collection of American Tonalist paintings at Oxford Gallery—representing what has to be one of the most significant private collections of Tonalist art in the U.S. It’s the first period show the gallery’s director, James Hall, has mounted in eight years, and it’s a revelation of this massive underground river of Romantic painting—a coherent and totally American aesthetic, which was more of a philosophical stance toward life and death than a set of techniques or subject matters. Tonalism is beginning to emerge and command the attention of critics with a big show that included Tonalist work earlier this year at The Spanierman Gallery and a huge scholarly tome, The History of American Tonalism, by David Cleveland. The movement flourished from the late 19th century to around the time of the Armory Show and it represents a diverse span of work, encompassing Inness as well as Whistler, and eventually, as Cleveland argues, it emerged to find its final embodiment, transformed, in the work of Abstract Expressionists like Rothko, Newman and Still. Tonalism explored ideas at the heart of literary Romanticism—Wordsworth, Blake, Keats, even Thomas Gray, and then half a century later in America, Thoreau, Emerson, Whitman—a vision of spiritual transcendence through a silent union with the natural world. These same principles align it with Asian traditions as well, especially classic Chinese landscape painting, which became a central inspiration for Burchfield, whose unique body of work represents a stepchild of Tonalism and is one of the most original achievements of 20th century art, as the Whitney’s retrospective proved last year.

The Oxford has been collecting examples of this work for nearly as long as the Halls have presided over the gallery—and, again, it’s one of those collections, like the Phillips, that reveals as much about the movement as it says about the taste of the collector. Some day, the 45 paintings in this collection could easily be worth a small fortune, if Tonalism emerges from obscurity—as it may have begun to do this year—as the Jungian shadow of European Modernism. As of today—though far more expensive than the typical fare at the Oxford—the work is listed at a fraction of the prices at Spanierman earlier this year, though the quality of Hall’s collection is of the first order. In other words, I wondered why I didn’t see the Memorial Art Gallery’s entire acquisitions committee in conference in heated conversation, trying to narrow down which six of these paintings it needed to claim before anyone else discovered them. This is an assembly of work worth it’s own small museum.

James first showed me a few of these paintings a couple years ago—quietly stepping into the little dehumidified room that serves as his vault—and I nodded with appreciation but just didn’t get it: they seemed unfocused, diffuse, foggy, and, well, so 19th century. They seemed both backward and provincial, a disaffected offshoot of the Hudson River school, or maybe a little school of painters who fell in love with Corot in their teens and just couldn’t get over it. Or maybe a splinter group of the American impressionists. Yet the scope of Tonalist painting is far more subtle and complex. You actually have to keep looking: they don’t yield their secrets at a glance. The point isn’t to offer a spectacular glimpse of the sublime magnificence of nature—here and there you can see Turner, as an influence, but these painters weren’t after that kind of Burkean sublimity—it’s more about absence, twilight, emptiness and obscurity. It’s about what’s behind and within what meets the eye. It’s about the lone poet, forgetting that he’s lost his way, looking up at the sky while the moon comes out, or a tiny figure who has just caught a trout, even though the little victory is dwarfed by the rain coming in behind him, and the struggle of the sun to emerge through the clouds overhead—so that he’s about to disappear into the rainfall that’s stalking him, merely a tiny detail in the cosmos of a Chinese scroll. One of the best paintings—with a red dot beside its number already—used to hang in Hall’s dimly-lit office, and until now it looked to me like a city scene done entirely in various shades of black. Lit up in the gallery, it’s a marvel of delicate modulation—in mid-range grays, much lighter than they looked above his desk—a few figures moving through a railway underpass, the glowing smoke of the locomotive barely visible in the distance, a composition that almost works as geometric abstraction and evokes the loneliness of city life, yet it also suggests the deep, meditative silence of a natural scene. Every one of these paintings rewards a long, lingering look, revealing more and more of itself, the longer you study it. These painters seemed to be most drawn to that brief moment at the very end of what photographer’s call the Golden Hour, when all the direct sunlight has fallen beneath the horizon and everything’s lit by a final glow of reflected light.

In their technique, the Tonalists seemed devoted to showing how many mysterious things oil paint can be made to achieve. Sometimes they loaded the canvas with paint so thick and rippled, it looks as if the image was done on a stucco wall. Other times, they thinned their paint to such a degree that the oil could pass for watercolor, one thin wash on top of another. Behind all of it appeared to be a conviction that, if you can unleash it through technique, oil paint will achieve things all on its own, evoking image and detail in unpredictable ways—rendering images that can be seen only from six feet away—undoubtedly revealing more than the painter actually intended. Up close, it can be a mess of scraped, rubbed, brushed, and smeared paste and yet as you move away from the canvas, the magic happens. The focus was just as much on the nature of paint, a work of art as a physical object with its own power and presence, as it was about seeing through the paint for a glimpse into the nature of the world.

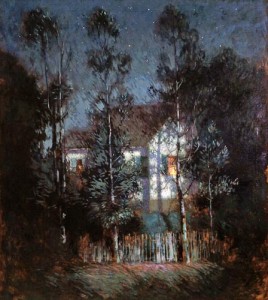

There are so many marvels in this show, it’s impossible to list them, though some of the highlights are Cornoyer’s The Lights in the Window, an actual night scene that seems to be lit by a full moon behind the painter’s back, The Flight into Egypt, by George Hitchcock, in which another full moon doubles as a halo around Mary’s head, Reflections of Spring, by Hugh Bolton Jones—a little concerto of early spring, all wet and cool and fragrant, in blues and blacks and whites, and the aforementioned scene of fishing, Sol’s Glory, by George Inness Jr. There isn’t a single dud in these four dozen paintings, and the chance to see them all on view at once illuminates the amazing prescience—and patience—of a shrewd collector like Hall, quietly buying up one after another of these hidden gems through many years of hunting, on the cheap, knowing that this overlooked contingent of artists will some day be honored for their quiet vision so seemingly antithetical to the mainstream of 20th century art—and yet, as it turns out, so invisibly integral to the shift of the art world’s center of gravity from Paris to New York in the 50s, and therefore to the primacy of American art ever since.

[…] the press release from the gallery. When I saw it I thought of the twilight and night scenes of Tonalism. This reproduction is pretty good, though the painting is actually darker than this and you have to […]