Danto’s paradiso

This piece from Hyperallergic is a great, accurate overview of Arthur Danto’s singular contribution to art philosophy. Reading After The End of Art was a liberating and crucial experience for me, though his conclusions at the end of the book were dispiriting. Essentially he asserted that, in the Sixties, art arrived at the end of the long history of its struggle toward greater and greater creative freedom. In that decade, and ever since, it was established that anything could be designated as a work of art, and therefore an artist could literally do anything as a means of expression. Everything was, and is, permitted, to echo Dostoevsky’s phrase, in a different context.

This piece from Hyperallergic is a great, accurate overview of Arthur Danto’s singular contribution to art philosophy. Reading After The End of Art was a liberating and crucial experience for me, though his conclusions at the end of the book were dispiriting. Essentially he asserted that, in the Sixties, art arrived at the end of the long history of its struggle toward greater and greater creative freedom. In that decade, and ever since, it was established that anything could be designated as a work of art, and therefore an artist could literally do anything as a means of expression. Everything was, and is, permitted, to echo Dostoevsky’s phrase, in a different context.

The question then becomes, why create art at all? If the need to push art “forward” toward something historically new is no longer possible, then why make art? Danto’s answer was that each individual has to answer that question, one person at a time, and that the answer to the question is baked into the artwork just as a philosophy of life is embedded in a person’s daily actions. Each individual has to explore and understand why he is creating something, in utter freedom–there is no obligation to do anything in any particular way. The work must justify itself, without relying on an historical context: no more schools of art to advocate one way of doing things over many others. (Danto’s point was that whatever virtues one way of doing things has over another, it isn’t because it’s fresher or more “contemporary” or new in the traditional sense or somehow an historical advance over what has come before.) His key insight was that Pop Art was the art movement to end all art movements, liberating all individual artists to do whatever they wished, and think for themselves, as individuals.

Whether Pop Art holds up now as something that’s still interesting, in and of itself, is another matter: he was thrilled by it because he saw it as a completely philosophical way of making art. It was a philosophical act, a statement about the nature of art, more than a finely crafted piece of work. What it implied–that art and life were now ultimately indistinguishable—mattered more than any physical or aesthetic qualities it embodied. In essence, as this overview points out, it was as if Hegel’s “end of history” as the destination of the world toward a state of spiritual freedom actually happened in the world of art in a particular decade in America. In the political realm? Not so much. (Especially in those countries living under the political system that grew out of Hegel’s philosophy as a certain fellow by the name of Marx interpreted it.)

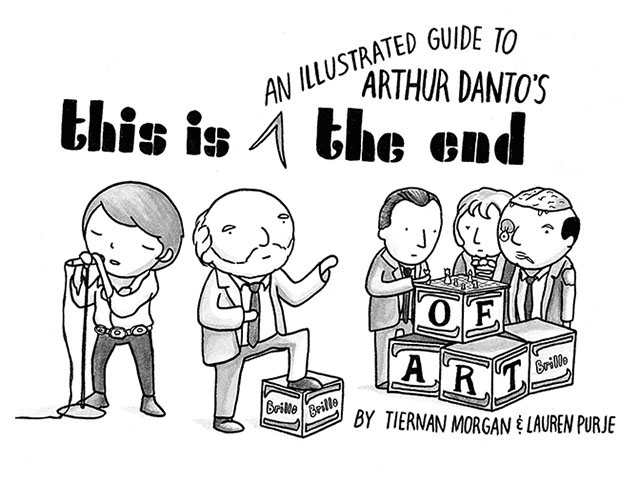

Here are excerpts from the piece, illustrated by my favorite Okie, if she’s still out there teaching. I think that’s supposed to be her up there doing her better-groomed distaff version of Jim Morrison . . .

It wasn’t Warhol’s subject matter that shocked the philosopher, but its form. Whereas Warhol’s paintings of coke bottles and soup cans were visual representations, the artist’s Brillo box sculptures — silkscreened plywood facsimiles of actual Brillo boxes — were virtually indistinguishable from the real thing. If one placed one of Warhol’s sculptures beside a real Brillo box, who could tell the difference? What made one of the boxes an artwork and the other an ordinary object?

Do the Brillo boxes represent some sort of art historical progress? Was art history heading in a discernible direction? Danto’s investigations into history, progress, and art theory, coalesced into his best-known essay, “The End of Art.”

According to Danto, the commitment to mimesis (representation) began to falter during the nineteenth century due to the rise of photography and film. These new perceptual technologies led artists to abandon the imitation of nature, and as a result, 20th-century artists began to explore the question of art’s own identity. What was art? What should it do? How should art be defined? In asking such questions, art had become self-conscious. Movements such as Cubism questioned the process of visual representation, and Marcel Duchamp exhibited a urinal as an artwork. The twentieth century oversaw a rapid succession of different movements and ‘isms,’ all with their own notions of what art could be. “All there is at the end,” Danto wrote, “is theory, art having finally become vaporized in a dazzle of pure thought about itself, and remaining, as it were, solely as the object of its own theoretical consciousness.”

Warhol’s Brillo boxes and Duchamp’s readymades demonstrated to Danto that art had no discernible direction in which to progress. The grand narrative of progression — of one movement reacting to another — had ended. Art had reached a post-historical state. All that remains is pure theory:

Of course, there will go on being art-making. But art-makers, living in what I like to call the post-historical period of art, will bring into existence works which lack the historical importance or meaning we have for a long time come to expect […] The story comes to an end, but not the characters, who live on, happily ever after doing whatever they do in their post-narrational insignificance … The age of pluralism is upon us … when one direction is as good as as another.

My disappointment with Danto’s book was twofold: as this piece points out, he suggested that art has meaning only in the context of a surrounding art world, with all of its assumptions about what to expect from art. Second, he suggested that the only way to appropriate techniques, styles, or schools of painting, from the past, was to present them ironically, as so many artists do now, from John Currin to Kehinde Wylie. He essentially, at one point, declared that a serious artist can’t simply paint the way Rembrandt or Vermeer did, because the work of those artists made sense only in the context of their historical period, with all of its cultural, philosophical and religious assumptions. If you paint another Night Watch, you’d better have your tongue planted firmly in your cheek. Really? Blake drew from the Gothic art of the past and created one of the most uniquely individual bodies of work in Western art, and it seemed to have more to do with universal and eternal realities of human life, as he saw it, and very little to do with anything else going on in art at the time, except for stylistic similarities to a few others, like Fuselli. The only irony in his work is one that he didn’t intend: the harder he strove to make his vision universal and timeless, the more idiosyncratic and personal it became. He wasn’t cleverly appropriating past styles and then presenting them with ironic commentary from some superior historical position: he was using them directly, honestly, sincerely, to convey exactly how he saw the world. It didn’t matter to him, or to us, that Sir Joshua Reynolds would have disapproved.

If Danto has been able to let go of philosophy the way he said goodbye to the notion of historical progress in art, then he might have prepared people to see the real imperative now: to become nothing but the person you are, in a unique individual way, as an artist. The greatest figures of the past for me are the ones who didn’t so much change the history of art as find a way to become themselves in paint, off in some little quiet cul-de-sac, while whatever was considered mainstream art at the time roared past, taking notice of them or not: Blake, Vermeer, Klee, Braque (after doing his bit for art history early on), Gorky, Porter, Avery, Matthiasdottir, Thiebaud, and, above all, Burchfield. Gorky and Braque in that list were figures who played key roles in the sequence of “advances” that led to the Sixties, but what makes them interesting to me are how idiosyncratic their work ultimately was: once Braque got past the theorizing of earlier Cubism, his work became unfathomably personal and mysterious, a luxuriant celebration of paint and visual experience that remains inexhaustible. In his Yale lecture, in the last year of his life, Porter talked about how the reality of life resided not in the general rule, but in the individual exception–what seems utterly perfect but could never have been predicted. It’s another way of saying, life is about irreducible human individuality, and painting should express nothing else.

So in answer to the question, why make art at all, I would suggest a modification of Dave Hickey’s heroic advocacy of beauty: make something you want to keep looking at. Make something others will return to again and again, wanting to see it. If it has implications that someone can write about or analyze or otherwise pick apart, fine, but that’s secondary. You don’t need art theory to know when you can’t take your eyes off something, or someone.

Next post: A perfectly serviceable philosophy of art, in my view, from the Kingston Trio.

Comments are currently closed.