The virtues of obscurity

Bill Santelli called my attention to this great Times story about Leo Bates, an artist whose career, once he went into seclusion, followed a trajectory somewhat like Vivian Maier’s, into obscurity and then out of it, after death. He dropped out of view after a big show at the Albright-Knox, which was itself a remarkable achievement, so he’d been on a path toward more conventional success, and yet gave up on it in favor of success in making the work itself. His devotion to the work, despite everything, is inspiring:

As SoHo boomed, Mr. Bates became more alienated. His working-class roots were at odds with the culture enveloping the scene he once knew.

“The glitz, glitter and boutiques. It became about fashion, money,” said his wife, a librarian who had lived with Mr. Bates in his Grand Street loft throughout the ’70s. “That wasn’t something that Leo…” her voice broke off. “He was a painter,” she said.

And in practical terms, he could not afford to stay. When he lost the lease on the loft, Mr. Bates decided to withdraw. In November 1978, he sold a batch of paintings. Using the proceeds, he made a down payment on 367 Seventh Avenue in Park Slope, moved into the apartment above the storefront and all but vanished.

“That’s the last time he sold anything,” Mrs. Bates said.

He was 34.

In the following years, with the help of his wife’s family, he bought two more walk-ups on the same block in Park Slope, and he became, at least in the eyes of the world, a landlord.

In Manhattan, he soon faded from people’s minds. He didn’t show up at Fanelli’s anymore, Ms. Fish said, and “if you didn’t see the person there, you just lost touch.”

In 1982, Mr. Bates went to a closing party for a show of Mr. Rappaport’s work on Downing Street in the West Village. As Mr. Rappaport recalled, Mr. Bates was upset with him, because Mr. Rappaport had used a small gift from his father to take out an advertising spread in Artforum magazine to promote the show.

“Fairly early in the evening, Leo got up after having a few drinks and he said: ‘Richard is a fool. He just demonstrated how closed the art world is and what a fool I am to even try,’ ” Mr. Rappaport remembered. “And he picked up a serving plate and hurled it at one of my paintings on the wall.” The two never spoke again.

Mr. Bates had a few paintings in group shows in the early ’80s, but from the time he moved to Brooklyn, virtually all that people saw in his hand were the signs he hung outside his buildings: apartment available, inquire inside.

“We didn’t talk to anyone about the art,” Mrs. Bates said.

Mrs. Bates worked in a private library at Bank of America, and they lived on her salary and their income from rentals, which Mr. Bates invested in stocks. But if Mr. Bates had stopped hanging out with painters, he had not stopped painting. In Brooklyn, he painted and drew obsessively. Asked why her husband had stopped selling his work, Mrs. Bates said: “He wanted to keep his body of work together. He wanted to show the progression.”

. . . . Looking at Mr. Bates’s work, it is clear that something happened when he left Manhattan and moved to Brooklyn. When he plunged into deep solitude, he found something new.

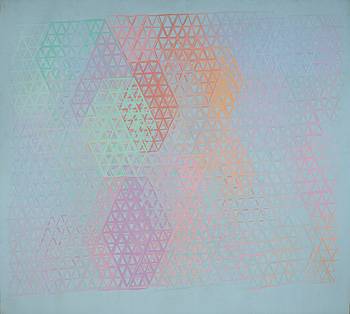

There were the muted tones of the Bowery years, the simple triangles, and then suddenly, an explosion of color, mesmerizing patterns.

After the initial burst, the paintings grew more austere. There was more negative space and the colors grew a bit fainter with the years, but the palette remained the same. As did his passion for geometry: Mr. Bates’s last paintings were huge X’s and chevrons that when examined closely revealed tiny grids of dabbed paint.

Mrs. Bates said she did not believe that her husband regretted his decision to work in obscurity. His goal had been not to pander to passing tastes, or to scatter his work to the four winds. He had just painted.

Comments are currently closed.