Inner compass

We’ve had a couple killing frosts already here, which is typical: snowfall by Halloween. And then it’s followed by a string of much warmer, Indian summer days, a temperate mix of sun and clouds, sometimes for weeks. One thing about Western New York, at least in my suburb, is that robins sing only into June, and then we hardly see them until the next spring. I have no idea where they go or why they don’t keep plucking worms from the grass all summer long. They retreat to more wooded areas or maybe properties where the birdbaths get cleaned more often than ours does. Or they just don’t like me. That’s probably it.

We’ve had a couple killing frosts already here, which is typical: snowfall by Halloween. And then it’s followed by a string of much warmer, Indian summer days, a temperate mix of sun and clouds, sometimes for weeks. One thing about Western New York, at least in my suburb, is that robins sing only into June, and then we hardly see them until the next spring. I have no idea where they go or why they don’t keep plucking worms from the grass all summer long. They retreat to more wooded areas or maybe properties where the birdbaths get cleaned more often than ours does. Or they just don’t like me. That’s probably it.

It makes me feel a little cheated. Every time I visit my cousin Brian in Laurel, Maryland, near Baltimore, I hear flocks of robins singing up and down his street, regardless of what month it is. I want to shout up into the branches, hey what gives? Yet, as the sun came out this morning, robins showed up again, way ahead of schedule, and started fighting for exclusive claim to the birdbath, and then half a dozen of them were hopping around in the front yard, tilting their heads to the side. Then, while I was sitting in my studio I heard one of them singing in a crabapple next door. This is something of an event around here for me—which may be sad commentary on my particular suburban life. A little more birdsong and, let’s be honest, three more blowout backyard parties per year—which would be three more than I usually have—and I’d be a pretty happy camper. Maybe the robin was announcing that winter isn’t coming after all, and we’ll finally get a local windfall from global warming. As I understand it, we’re one of two places on the globe where temperatures have been declining steadily as they rise everywhere else on the planet.

Whatever inspired him to sing, I’ve decided to take that little avian tune as a good omen for breaking old patterns. Recently, I resolved to shift my painting more resolutely toward a new method I’ve followed off and on for years, but without being able to stick with it. In the past, I’ve borrowed Edwin Dickinson’s term, premier coup—letting the first strike stand without reworking, painting quickly—to describe this method. But I’ve misled myself by associating these paintings with the sense that I’d have to finish them in only a day, or with some kind of stopwatch in mind, as I believe Dickinson may have done, as a discipline. I’m perfectly capable of doing that. I’ve done it many times, sometimes with great results. Many times, though, just the opposite. In both cases, the speed of execution is there, easy to see, in the brushwork, part talent and part luck, when it works. But what always gets in my way is thinking first about how much time I’m spending in the work. The amount of time invested in this sort of painting isn’t the point. It’s more about the quality of the paint, and keeping the level of detail at a certain level, with only a certain level of finish, regardless of how long it takes to apply the paint—though these paintings will always take a fraction of the time my highly realistic work requires, if I’m focusing on these things.

Earlier this week, I took a series of photographs, hoping to put together a small collection of images that would set me up for a series of half a dozen smaller paintings over the next few months. Then other obligations began to eat into my week, so I wondered if I shouldn’t try another premier coup, just to keep the rhythm of work going, as a bridge to next week, when I can do nothing but paint. Rather than be in the frame of mind for finishing something to include next year or the following year, why not just do something to please myself?

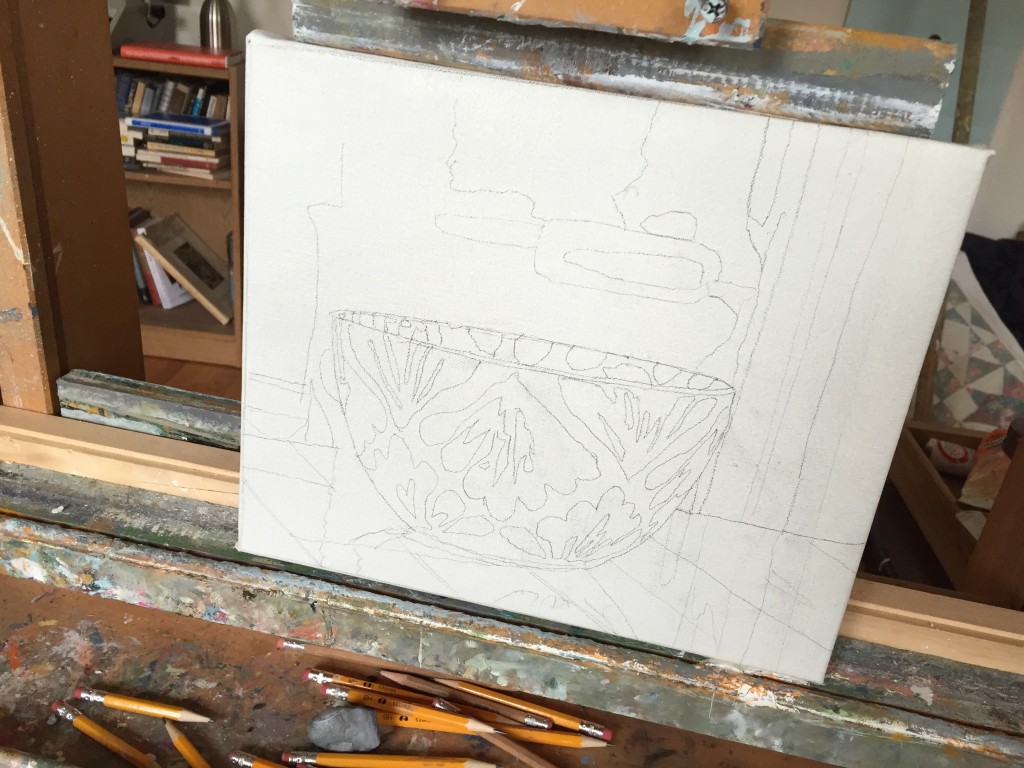

So I went back and looked through this file of photographs I’d just taken of small ordinary household objects—a vase, some little bowls we bought not too long ago—and I found one that I’d rejected as almost too simple. Just a bowl, nothing else, on the edge of our kitchen table, which has a blond-and-honey surface of poly-coated maple. It’s a challenging surface to depict effectively which may be why I put it aside. Now the simplicity of the image seemed just what I needed, given my new intent—to do something unassuming for its own sake, the way Manet painted a little bunch of asparagus tips as a gratuity, nothing at stake in it, for a collector who bought a larger painting.

Now I can’t wait to pick up a brush tomorrow morning. The key to this change in attitude—which may help me stay on course with a series of paintings like it—is that I’m doing it simply to hold fast to a certain feeling in the application of the paint. Not how many days it takes. Not whether it will look like work I’ve done before. Once I got my head organized around that feeling—to make each spot of paint exactly the sort of spot I want to see in order to evoke a certain level of verisimilitude, regardless of whether anyone else will recognize the quality of the results—then the desire to push paint around sprang up on its own. But it was also partly that I saw, in the discarded shot of the bowl, patterns of color that hadn’t struck me before and a certain way of composing a picture from it where the forms would work together, if I could do it properly. The inner compass is to keep feeling my way forward through a certain way of applying a certain consistency of paint. If I lose that, a sense of obligation begins to seep into the process, and an act of creation becomes a job. This is one of those “lessons” I’ve learned dozens of times, and keep having to relearn every time I start a new painting, and yet as often as it comes into focus, it just as often slips away, because time pressures seep in as you slip into wanting more from the act of painting than the act of painting itself.

Comments are currently closed.