Philosophy and painting

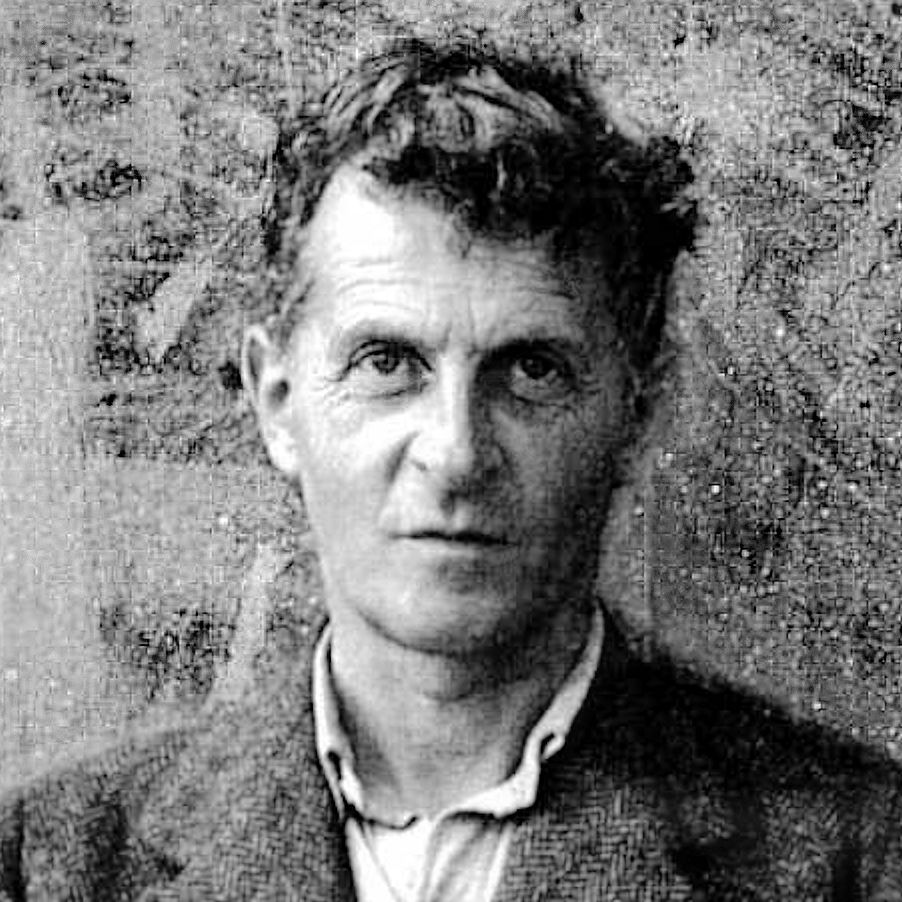

I’ve been reading above my pay grade, as it were, for the past couple weeks, delving once again into On Certainty, by Ludwig Wittgenstein. I minored in philosophy at the University of Rochester, and as a senior I took a graduate seminar mostly to study The Blue and Brown Books, and Philosophical Investigations. When I say “seminar”, I mean that I, and two grad students, met for several hours every week in the office of a tall Afro-American professor who packed tobacco into his pipe and inhaled the smoke (as he would have with a cigarette) for the duration of our conversation. He didn’t lecture us, but played Socrates, as Ludwig often did, too, as we thought our way forward. I was often baffled, if not completely lost, but not always. He was kind, and he never disparaged my beginner’s efforts.

I came out of it knowing what is commonly known about Wittgenstein: that he believed the cure for his philosophical obsessions was to see as clearly as possible how language was fooling him into asking questions, or coming up with theories, that were essentially pointless. Philosophy was a cure for philosophy. (Yet he kept doing it. Continuing to ask a question with no answers somehow matters.) This encouraged me because of my own history, at that point, of asking philosophical questions that had no answer, at least not the way ordinary questions have an answer, embedded in a sensible pattern of behavior, a “way of life.” My reading in that class supported something I’d come to see, through reading Kierkegaard a few years earlier on my own time: that my own mind was unable to recognize its own built-in limitations and that those limitations created an apprehension of life disconnected with “what was the case” as Wittgenstein might have put it. To have a moment of insight like that, as I had while reading Kierkegaard, is enormously freeing. Though the sensation of being released from a philosophical brain-freeze (as it were) wears off, the trap of thinking in a particular way never regained its power, and I’ve never let go of the understanding I had at that moment nor the ability to step away from what I might think or feel, at any given time, are inescapable certainties.

This, I think, was Wittgenstein’s struggle: to free himself from intellectual patterns of thought that masqueraded as certainties by becoming conscious of everything the mind presumes as certain. For him, it seems, all certainties are, in fact, at some level unproven and unprovable. They’re simply there as the foundation of how we live and think. The “hinge propositions,” as he called them, serve a role in our life of being almost unconscious behavioral foundations—I have two hands, the earth is ancient, the sun will come up tomorrow, doing good is worthwhile in and of itself, and so on. (I doubt that he would agree that all of those work as hinge propositions, especially the lyric from Annie, but you get the idea. He might have whistled that third one: he could whistle nearly anything.) These undergird behavior in such a way that they don’t even qualify as knowledge, but rather as unquestioned, structural elements of our way of life, our behavior. It wouldn’t make sense to try to prove them: in other words, to doubt them and then offer convincing proof that they are true. They just are. Everyone accepts them without thought. Here’s a sample from On Certainty:

- Doubting and non-doubting behavior. There is the first only if there is the second.

- One might say: “ ‘I know’ expresses comfortable certainty, not the certainty that is still struggling.”

- Now I would like to regard this certainty, not as something akin to hastiness or superficiality, but as a form of life. (That is badly expressed and probably badly thought as well.)

- But more correctly: The fact that I use the word “hand” and all the other words in my sentence without a second thought, indeed that I should stand before the abyss <of Descartes’ methodical doubt> if I wanted so much as to try doubting their meanings—shews that absence of doubt belongs to the essence of the language game.

The “language game” is how people negotiate a “form of life” for Wittgenstein, and within a language game there are these essentially apodictic structural elements of “how things are” that go unquestioned for the entire game to proceed. They are the equivalent of rules, but aren’t even that explicit: I have two hands, the earth is very old, and so on. It’s integral to how we live and what we believe. The numbered thoughts in his book are transparently easy to understand in a superficial way—the language is conversational and simple and clear. The thoughts often sound so obvious that you wonder why he is wasting your time writing them down. But the compounding effect of reading the book is that things become less and less transparent the more you think about them, which I’ve been attempting to do.

It isn’t easy. Decades have passed since I quietly enjoyed the second-hand pipe smoke of my graduate seminar even when the words being exchanged seemed far more opaque than the smoke. I discovered On Certainty maybe a decade ago and read it once, and then it sat on my shelf untouched until a couple weeks ago. Having reread most of it, and some commentary about it on the Internet, for relief, I’ve moved on to a couple other books, most notably an affectionate memoir by Norman Malcolm, a colleague of Wittgenstein’s in Britain who came to Princeton and then moved on to Cornell, in Ithaca, a few hours from here.

The memoir is wonderful, a brief recollection of what the Viennese philosopher was like: how intensely judgmental and difficult and volatile he could be with friends, and yet how kind and grateful and humble he was when he wasn’t engaged in some internal battle with his demons. Wittgenstein’s letters glow with his intense need for conversation and friendship and an amiable sense of self-deprecating humor. I had the impression, from Malcolm’s memoir, that Wittgenstein was under a constant internal compulsion to think in ways that he often found painful, trying to untie knots of questions that gave rise to much of Western philosophy, and lashing out at people on impulse under the wearying strain of having to sustain a level of thought that always drained him. And yet he was never happier, in a certain sense, than when he was doing philosophy—“it’s the only thing that bucks me up”—either alone, in his thinking and writing, or with others in his Socratic sessions, during which he was continuously trying to reignite insights that, as he put it, might “let the fly out of the bottle.” The fly being his conscious, thinking mind. The bottle being philosophy itself.

I’m hoping to come away with some modest insights from these books that might shed light on the difficulty of putting into words what it is that visual art can do. I think of it as something akin to “hinge propositions” though a painting is far from a proposition; or at least that’s true of the kind of painting I esteem. What a painting conveys resides at some level near those hinge propositions. It’s an inadequate metaphor, and doesn’t really work, but you don’t go to a painting for knowledge, and yet what you get from it is more than pleasure. I guess it might sound as if I’m suggesting to you, in a ridiculous way, that I know something ineffable (Wittgenstein would cut me down for the “know” in that sentence) that you ought to know, and therefore you should listen up. Not so. Since I was in my teens, I’ve been intensely conscious that not only do I not know certain essential things about life, in an intellectual way, but that they can’t be known, properly speaking. They can only be lived—for lack of a better word. (A lot of “better words” are missing when it comes to talking about art, and what matters in life.) Wittgenstein said: “We feel that even when all possible scientific questions have been answered, the problems of life remain completely untouched.” (He was wary about science, but I think he was talking about reasoning itself, not simply science.)

I think art is one way of attempting to be aware in a particular way that doesn’t consist of knowledge, while, at the same time, trying to create something that points toward life in such a way that other people can share briefly in this same awareness. The irony of course is that we painters, if we knew what’s good for us, probably ought to drop the brush and just be aware in this way–do less, and be more–as I think Wittgenstein was attempting when he resigned from teaching philosophy at Cambridge and came across to Atlantic to Ithaca in order to live with his friends. But, once here in the U.S., he couldn’t resist drafting On Certainty. He couldn’t just live. His fate was to keep trying to philosophize his conscious act of questioning into a happy awareness of its own limits—which were limits common to everyone else’s ability to think, at least within a given “way of life”. Even earlier, he’d tried to get away from the struggle of teaching by escaping to a monk-like solitude on the coast of Ireland, and elsewhere (even once contemplating a life as an actual monk.) It’s hard to know if this was to flee philosophy or be able to do it at its highest pitch. But what makes him unique: there may not have been any difference between the two, for him.

Comments are currently closed.