Okay to like

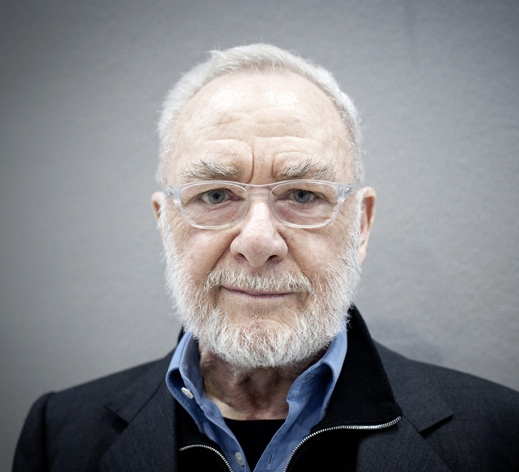

From Forty Years of Painting, the catalog for a great Gerhard Richter retrospective I saw in 2002 at the Museum of Modern Art, some thoughts on when he was an obscure and struggling artist. In the interview, he stresses how his aims, in representational work, are classical. It’s a tremendously honest discussion: “I wanted to be seen.” When a friend of mine saw his work recently he said, “I think he’s the greatest painter alive.” Mission accomplished, Gerhard. My interest in Richter is that his work found a place in art history mostly by simply being incredibly good, but also by finding his own way to paint, on his own, without concerning himself with the notion of “progress” or “movements” in art. His sense of alienation from the art of the 60s and 70s makes him a forerunner for everyone now who has to see art as a uniquely individual pursuit, redefining what’s “new” in a completely individual way. You can’t return to the past, but to employ techniques and methods from the past doesn’t require you to be ironic about them. I love the term “tin art” Richter uses. And yet apparently he was pals with Blinky Palermo and “Bob” Ryman, who would seem to be in the minimalist club, so his work is a natural affirmation of what he most values rather than a reaction against other work. He’s candid about his vulnerability in the 60s: “He was a real artist. Not like me.” The interviewer tries to pin down whether Richter is being ironic in his embrace of tradition, whether Richter is really just doing a postmodernist dance, undermining culture, and so on, but Richter answers like a politician about the “absence of the father.” Say what? It’s amusing; yes, the loss of authority, the loss of “the father,” I get it, but he’s still wriggling away from the question.The century as a whole was problematic for him, not to mention the current century, and it’s clear how his feelings are anchored, even though in his abstracts he certainly found a way to embrace modernism. The interviewer manages to fuse modernism and postmodernism into this one sentence as the 20th century club Richter didn’t want to join (his abstracts weren’t under discussion) and Richter agrees he didn’t want to be a part of it:

Your evocation of the classical was basically a response to the whole mood of the late 1960s, early 1970s, where the general rules were: Away with the old; Everything must be new; and Everything must be a cultural critique.

Yes. Exactly.

But that interpretation differs from what many people seem to think the work is about.

Oh really!

Some critics seem to regard the 48 Portraits as an empty, almost stamp-like array of cultural icons. Why do you think it has had strong response?

If it was only postage stamps it wouldn’t be as elaborate, and there wouldn’t be as much trouble. It is too big and there is too much presence and always people wonder what it is about. Women are angry because there are no women. It keeps upsetting people again and again. People are always upset when confronted with something traditional and conservative, and therefore they don’t want it. You’re not allowed to do that; it is not considered to be part of our time. It’s over, reactionary.

Some critics explain it to themselves–make it okay to like–by arguing that it’s an exercise in rhetoric, the rhetoric of a certain kind of representation of culture that questions or nullifies that culture’s authority.

And as I mentioned, you also have the psychological or subjective timeliness of the father problem. This affects all of society. I am not talking about myself because that would be rather uninteresting, but the absence of the father is a typical German problem. That is the reason for such agitation; that is why this work has such a disquieting effect.

So it is about restoring a sense of history that has been broken or truncated.

It’s not a restoration. It is a reference to this loss. It takes account of the fact that we have lost something. It asks the question of whether or not we need to do something. It is not about the establishment of something.

A question of whether what has been lost can be brought back or not?

Yes, but I don’t believe that it comes back.

Was making the paintings a way of putting those images out to see whether they still exerted power on their own?

That was not my intention. My intention was to get attention. [Laughter] I wanted to be seen.

Bruce Nauman once made a neon with the text, “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths,” which he put in the window of his studio like a beer sign. That piece was addressed both to himself and to the public.

That’s good!

And what appeared to be a declaration was really a question: “Do you believe this? Do I believe this?” Is there any parallel between what he was doing and what you’re after?

Yes, I believe that there is something like that. That’s possible. But I have too much respect for Bruce Nauman to simply claim that we share the same concern, that we are thinking about the same things. It doesn’t work like that.

Another way of approaching the problem might be to talk a little bit about your decision to copy Titian’s Annunciation or your interest in landscape.

It is all the same motivation.

In other interviews, you’ve suggested that using nostalgia or using an anachronism was a way of being subversive. Bur painting in traditional modes can also involve an assimilation of traditions. Were you employing these images as a tool for upsetting the fixed ideas of the avant-garde, or were you reaffirming the basic paradigms to which you resorted? Were they primarily a tool, or a goal?

That is too difficult.

Alright, but take the landscapes and the Titian copy: not only was the style in which they were painted a departure from modernism, but so were the images. The idea of someone in your position painting a Titian or painting a beautiful landscape in a somewhat romantic way was bound to get a reaction, was bound to make people say, “What is he doing?”

On the one hand, it was a polemic against this annoying modernist development that I hated. And, of course, the assertion of my freedom: “Why shouldn’t I paint like this and who could tell me not to?” And then the affirmation was naturally there, the wish to paint paintings as beautiful as those by Caspar David Friedrich, to claim that this time is not lost but possible, that we need it, and that it is good. And it was a polemic against modern art, against tin art, against “wild art”—and for freedom, that I could do whatever I wanted to.

Tin art?

Much modern stuff looked like aluminum. Modern, pure, Minimalism was going on at that time. I remember just a little story that took place where I was first in New York with (Blinky) Palermo. We had some photographs of our work—just in case. And we showed them to someone—I think it was Bob Ryman—and I thought that he would, of course, prefer the abstract paintings, but he was only interested in my first landscape, which was Corsica.

And I was so surprised that he liked this painting. I thought, he is a modern artist, a real artist, not like me. But he liked it.

Comments are currently closed.