A drawing a day

During the recent afternoon I spent with Tom Insalaco at his home studio, I saw some of the amazing work he’s done over the past several decades. It’s a measure of his humility and generosity that he spent less time showing me his own work than he invested in introducing me to—or reminding me of—great work from other contemporary realists.

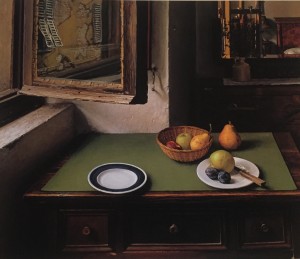

When he could have been pulling big paintings out of storage for me to photograph, instead he handed me a catalog of work by Richard Maury, a slim set of wonderfully printed plates from a show more than a decade ago at Forum. He pulled it out the the midst of hundreds of books Tom keeps on his shelves, including the entire catalog raissone of John Singer Sargent. Tom has spent a lot of time in Italy and ran into Maury there once:

“He’s wonderful. In one of his paintings, you can sense the terra cotta under the glaze on a little ceramic jar. You can sense the depth of the glaze. We found his house in Florence and who comes walking out the door but his wife. I was in Florence and was walking to a church to look at Masaccio, and we stopped a guy with red hair, and he said something and I said something . . . and it was Richard Maury. I didn’t realize it at the time. He was speaking in Italian, but he knew the ins and outs of English. He really had bright red hair back then.”

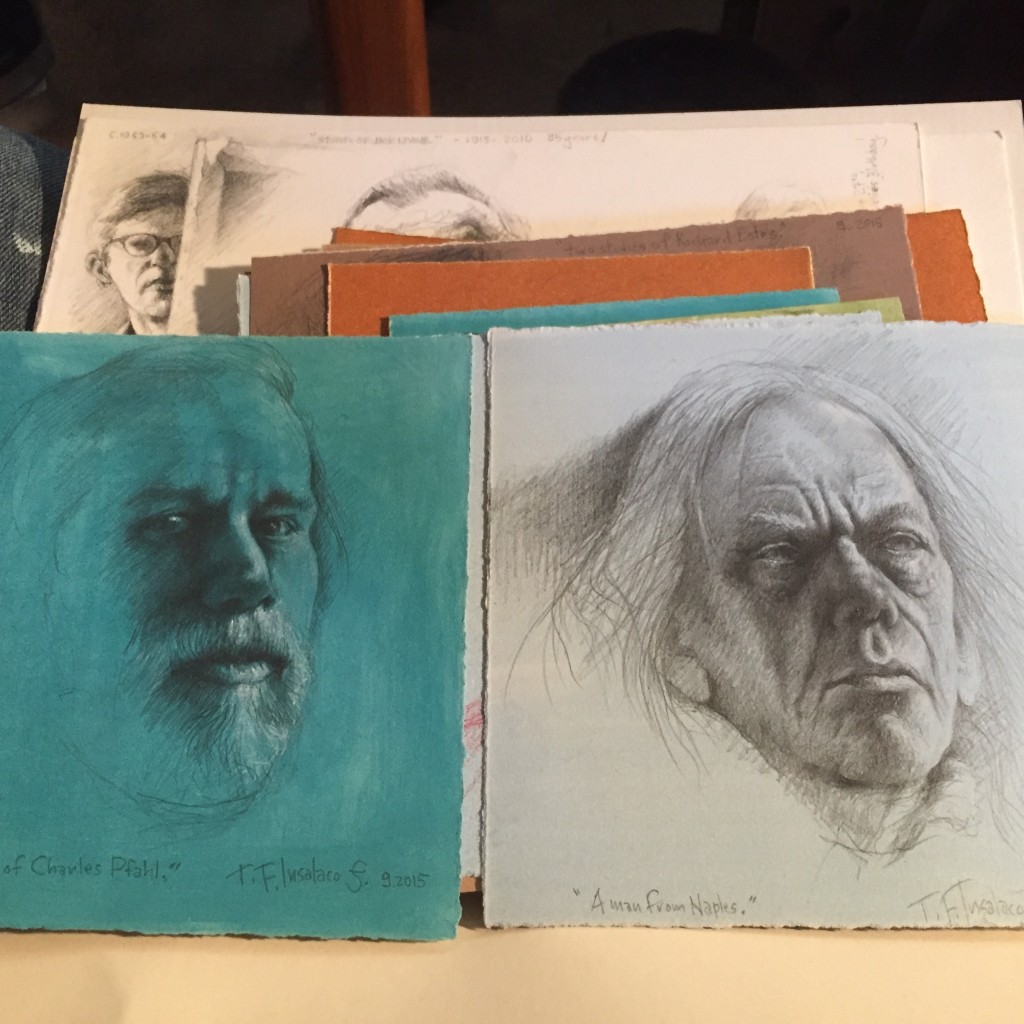

We talked for several hours, and Tom showed me dozens of drawings from a collection of the ones he has done every morning, without fail, on sheets of rag paper he has prepared by tinting them with oil—“It has to be rag paper.” Working from the overall middle tone he lays down, he creates portraits of people from photographs in the Renaissance manner, adding darker tones the usual way and then highlighting with white. (I recently skimmed through a catalog from the fantastic Durer show of drawings and prints at the National Gallery of Art in 2013 and was surprised by how intensely white Durer’s work was in those highlighted areas.) What was impressive was the size of that sheaf of sketches—Tom draws every morning, first thing, before doing anything else. Up, out of bed, he begins drawing immediately. When he’s done, he gets a little breakfast and then it’s on to his easel at the front of the house.

I’m guessing that Tom is in his mid-70s now, but hasn’t slowed down at all. He has a better memory than I do, and recalls things I’ve told him in passing about my wife and brother and parents, and also comes up with names of specific paintings by artists who don’t even ring a bell with me. He has no patience with contemporary art, and his recent visit to the new Whitney nearly enraged him when he saw the floor of one gallery space covered with a foot of mud—a recent installation.

“I don’t know if you’ve been to the new Whitney. Last time I was in there I screamed. I said why don’t you have the art, instead of this? There was a room full of mud, twelve inches deep. They probably thought they needed to call the police. It was chicken shit. They have so many great paintings. Edward Hopper’s Sunday Morning. Jack Levine’s Feast of Pure Reason. Why don’t they hang that?”

I timidly suggested that the Stella retrospective there now might help ameliorate the effect of the mud, and he allowed that this might be the case, but still . . .

It’s refreshing to talk with someone so candid and unguarded about how he feels when confronted with much of what’s happened to visual art. What I don’t understand, I told him, is why a curator in Western New York isn’t putting together a retrospective of Tom’s work, which reached epic proportions in a trilogy of paintings he did to commemorate the death of his brother a couple decades ago—he was a Buffalo police officer and was murdered by a participant in a domestic fight. One moment his brother was walking up to the door of the house; a few seconds later, he was dead, shot by the man he had come to restrain. Those paintings are monumental; but Insalaco has been building on that work ever since, drawing mostly from Renaissance precursors for his methods, with a bit of Dali tossed in. He was told a year ago or so that he has been invited to exhibit more often in the Memorial Art Gallery’s Finger Lakes Exhibitions than any other artist in Western New York—it’s the most prestigious juried exhibition open to all artists this side of Albany. So why isn’t someone putting together a definitive survey of what Tom has done throughout his career? He wasn’t even included in the most recent Finger Lakes. It would be a wonderful exhibit.

Comments are currently closed.