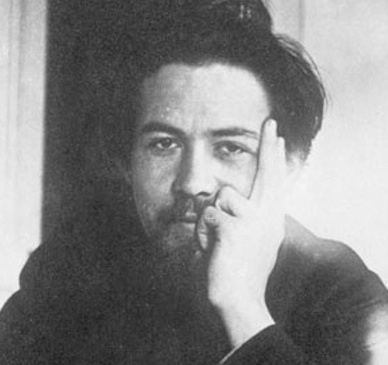

Chekhov’s flock of birds

For free via Amazon Prime, yesterday, I watched a hard-to-hear-with-aging-ears version of The Three Sisters, directed by Sir Olivier, and featuring him in a central role, from 1970 or so. It’s basically a stage play, produced as a stage play with some more elaborate backdrops, performed as you would see it on a Broadway stage. It was the first time I’ve watched or read the play in decades, and I got drawn into it for the full 2:20, even though I was constantly imagining how impatient younger people would be as they watched it. What I was thinking, though, was how much nothing has changed since Chekhov wrote the play, except that our aristocracy is in large part newly rich, and our bourgeoisie is what’s shrinking and disappearing–not the aristocracy, which is fading away in the play, during the last years of the 19th century. But the dynamics are the same: the world is defined by the vulgarity of the culture driven by new access to wealth and the decline of older values that once gave meaning to life. But I remembered, as I watched, how much Chekhov could pack into a play: many of the philosophical reflections by these idle characters about life remain just as powerful. Why are we doing anything at all? What is the point of all this? Why is it that no matter what we do, since we always want something else, we’re always looking toward some other place or person for happiness? I remember first reading him in college and our professor pointed out that he’s only one step behind Beckett and the theater of the absurd, and you can see this constantly in the play, but Chekhov has heart, where the absurdists are all head. Beckett transcends any quibbling expectations you bring to him, but I’d much rather sit through Chekhov than Beckett. Anton sees the same absurdity and mystery as Sam, but he feels the plight of the characters and shows how it enacts itself in actual daily life, rather than a stylized stripped-down setting. (Again, not to knock Beckett, who is one of my favorites.) Aristocratic characters dream of the life of laborers: how wonderful it would be to get up in the morning and drive a bus! (A little humorous nod to Tolstoy at the end of his life, I think. But it’s true. Many of us think the life of a contractor or plumber or motorcycle mechanic would be far more satisfying than “the life of the mind”. Painting is another way to avoid “the life of the mind” for me, but that’s another story.) Chekhov is always funny and absolutely accurate–and chilling even when he’s funny. I started watching another, more recent production of the play on film, with Kristin Scott Thomas, to see if it was easier to hear the dialog, and it is–for another day–and it actually looks less mannered, maybe closer to a film than a play. But Olivier’s version conveyed the power of the story, which is moving, full of affection for the little troupe of lost souls trapped in a town 900 miles from their beloved Moscow. It would be hard to make a mess of Chekhov, though I’m sure it can be done.

For free via Amazon Prime, yesterday, I watched a hard-to-hear-with-aging-ears version of The Three Sisters, directed by Sir Olivier, and featuring him in a central role, from 1970 or so. It’s basically a stage play, produced as a stage play with some more elaborate backdrops, performed as you would see it on a Broadway stage. It was the first time I’ve watched or read the play in decades, and I got drawn into it for the full 2:20, even though I was constantly imagining how impatient younger people would be as they watched it. What I was thinking, though, was how much nothing has changed since Chekhov wrote the play, except that our aristocracy is in large part newly rich, and our bourgeoisie is what’s shrinking and disappearing–not the aristocracy, which is fading away in the play, during the last years of the 19th century. But the dynamics are the same: the world is defined by the vulgarity of the culture driven by new access to wealth and the decline of older values that once gave meaning to life. But I remembered, as I watched, how much Chekhov could pack into a play: many of the philosophical reflections by these idle characters about life remain just as powerful. Why are we doing anything at all? What is the point of all this? Why is it that no matter what we do, since we always want something else, we’re always looking toward some other place or person for happiness? I remember first reading him in college and our professor pointed out that he’s only one step behind Beckett and the theater of the absurd, and you can see this constantly in the play, but Chekhov has heart, where the absurdists are all head. Beckett transcends any quibbling expectations you bring to him, but I’d much rather sit through Chekhov than Beckett. Anton sees the same absurdity and mystery as Sam, but he feels the plight of the characters and shows how it enacts itself in actual daily life, rather than a stylized stripped-down setting. (Again, not to knock Beckett, who is one of my favorites.) Aristocratic characters dream of the life of laborers: how wonderful it would be to get up in the morning and drive a bus! (A little humorous nod to Tolstoy at the end of his life, I think. But it’s true. Many of us think the life of a contractor or plumber or motorcycle mechanic would be far more satisfying than “the life of the mind”. Painting is another way to avoid “the life of the mind” for me, but that’s another story.) Chekhov is always funny and absolutely accurate–and chilling even when he’s funny. I started watching another, more recent production of the play on film, with Kristin Scott Thomas, to see if it was easier to hear the dialog, and it is–for another day–and it actually looks less mannered, maybe closer to a film than a play. But Olivier’s version conveyed the power of the story, which is moving, full of affection for the little troupe of lost souls trapped in a town 900 miles from their beloved Moscow. It would be hard to make a mess of Chekhov, though I’m sure it can be done.

The worldview of the play in a few quotes:

IRINA. Tell me, why is it I am so happy today? As though I were sailing with the great blue sky above me and big white birds flying over it. Why is it? Why?

CHEBUTYKIN [kissing both her hands, tenderly]. My white bird. . . .

IRINA. When I woke up this morning, got up and washed, it suddenly seemed to me as though everything in the world was clear to me and that I knew how one ought to live. Dear Ivan Romanitch, I know all about it. A man ought to work, to toil in the sweat of his brow, whoever he may be, and all the purpose and meaning of his life, his happiness, his ecstasies lie in that alone. How delightful to be a workman who gets up before dawn and breaks stones on the road, or a shepherd, or a schoolmaster teaching children, or an engine-driver. . . . Oh, dear! to say nothing of human beings, it would be better to be an ox, better to be a humble horse as long as you can work, than a young woman who wakes at twelve o’clock, then has coffee in bed, then spends two hours dressing. . . . Oh, how awful that is! Just as one has a craving for water in hot weather I have a craving for work. And if I don’t get up early and work, give me up as a friend, Ivan Romanitch.

***

VERSHININ . . . . I think that I do know and thoroughly grasp what is essential and matters most. And how I should like to make you see that there is no happiness for us, that there ought not to be and will not be. . . . We must work and work, and happiness is the portion of our remote descendants [a pause]. If it’s not for me, but at least it’s for the descendants of my descendants. . . .

TUZENBAKH. You think it’s no use even dreaming of happiness! But what if I’m happy?

VERSHININ. No, you’re not.

TUSENBAGH [flinging up his hands and laughing]. It’s clear we don’t understand each other. Well, how am I to convince you?

[MASHA laughs softly.]

TUSENEACH [holds up a finger to her]. Laugh! [To VERSHININ] Not only in two or three hundred years but in a million years life will be just the same; it doesn’t change, it remains stationary, following its own laws which we have nothing to do with or which, anyway, we’ll never find out. Migratory birds, cranes for instance, fly backwards and forwards, and whatever ideas, great or small, stray through their minds, they’ll still go on flying just the same without knowing where or why. They fly and will continue to fly, however philosophic they may become; and it doesn’t matter how philosophical they are so long as they go on flying. . . .

MASHA. But still, isn’t there a meaning?

TUZENBAKH. Meaning. . . . Here it’s snowing. What meaning is there in that? [A pause.]

MASHA. I think man ought to have faith or ought to seek a faith, or else his life is empty, empty. . . . To live and not to understand why cranes fly; why children are born; why there are stars in the sky. . . . You’ve got to know what you’re living for or else it’s all nonsense and waste [a pause].

***

MASHA. Happy people don’t notice whether it is winter or summer. I think if I lived in Moscow I wouldn’t mind what the weather was like, . . .

VERSHININ. The other day I was reading the diary of a French minister written in prison. The minister was condemned for the Panama affair. With what enthusiasm and delight he describes the birds he sees from the prison window, which he never noticed before when he was a minister. Now that he’s released, of course he notices birds no more than he did before. In the same way, you won’t notice Moscow when you live in it. We have no happiness and never do have, we only long for it.

***

IRINA [lays her head on OLGA’S bosom]. A time will come when everyone will know what all this is for, why there is this misery; there will be no mysteries and, meanwhile, we have got to live . . . we have got to work, only to work! Tomorrow I’ll go alone; I’ll teach in the school, and I’ll give all my life to those who may need me. Now it’s autumn; soon winter will come and cover us with snow, and I will work, I will work.

OLGA [embraces both her sisters]. Time will pass, and we shall go away for ever, and we shall be forgotten, our faces will be forgotten, our voices, and how many there were of us; but our sufferings will pass into joy for those who will live after us, happiness and peace will be established upon earth, and they will remember kindly and bless those who have lived before. Oh, dear sisters, our life is not ended yet. We shall live! . . . . it seems as though in a little while we shall know what we are living for, why we are suffering. . . . If we only knew — if we only knew!

CHEBUTYKIN [humming softly]. “Tarara-boom-dee-ay!” [Reads his paper.] It doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter.

OLGA. If we only knew, if we only knew!

Comments are currently closed.