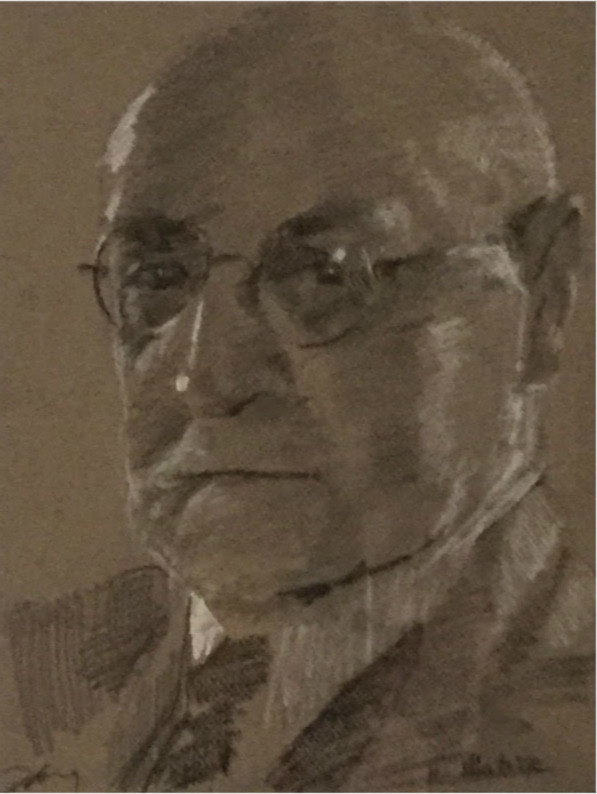

Shadow of his smile

Peter Schjeldahl implies it’s a toss-up who won the contest for Best Painter of the 20th century, Picasso or Matisse, who were in constant friendly competition. (He missed his best metaphor when it comes to these two giants: the Beach Boys vs. The Beatles. I’m going to Buffalo to hear Brian Wilson perform Pet Sounds on its 50th anniversary in September; the album that inspired the Beatles to create Sgt. Pepper’s.) I greatly favor Matisse; the more I study his work, the richer it becomes. I’ve been reading a lot about him for a couple weeks, filling in the gaps of my knowledge about his career, and it’s fascinating how it oscillated back and forth, twice, from the soft post-Impressionistic brushwork of his early paintings and later during the period in Nice–which is usually considered a kind of backsliding–to the two more experimental periods when his edges got harder and he came as close as he could to pure abstraction. That second category includes the epic paintings he did after returning from Morocco (before Nice), which were the subject of a revelatory show at MoMa in 2010, and then the final cut-outs. So once again, I’m reading what he wrote, and what has been written about him, and I’m studying his paintings with envy. He’s been a constant example throughout my life, always at my back as I work, making me feel untrue to his example at every turn. I imagine he would be smiling tolerantly if he saw what I do. It’s even more frustrating to reflect on his life and work when you’re in a hiatus from painting, as I am now, because of other obligations, especially when you can visualize about three dozen paintings you’d love to be doing. So, out of that frustration, I decided to start drawing once a day, if I can, for an hour or so, in what time I have available–I can’t remember the last time I drew regularly. I don’t count as drawing the guidelines I put down on canvas. I decided to do what Tom Insalaco has been doing–he showed me the results when I visited him late last year at his home in Canandaigua–a series of quick, daily portraits on tinted paper. He tints his with an oil wash, but I bought a small sheaf of pastel paper in various shades of gray, along with some white and black charcoal. Simple tools for an hour or so of work. A few evenings ago, with the news on TV, I sat on our couch and worked from a screen capture I’d done of Matisse at his easel, a still shot taken from a documentary about him on YouTube. The camera had been aimed at his face from behind his sitter, and I’d frozen it at the moment when he looked away from his easel toward his subject. I used the shot, on the screen of my laptop, sitting on the cushion beside me, to do the drawing on my lap, starting with some orientation marks and then working with areas of light and dark, without establishing any lines except toward the end–with a stroke of white charcoal along the top edge of his collar and a single dark line between his lips. I had to go back over the ear, and the proportions of eyeglasses to mouth and nose, as well as the position of the eyes, but because I worked with a very light touch at the start you can’t really see the corrections. I had never tried this classic technique with the white charcoal on tinted paper, working from a mid-value and putting down simply the darker and lighter tones. (I added some subtle areas with graphite.) The most remarkable and enjoyable part of it was that most of the work, all those mid-values, were already done, tinted into the paper. The results come from minimal marks–though hardly as minimal as the line drawings Matisse perfected. (See what I mean? He’s always there looking on.) The results pleased me and also made me smile: he looks like a banker sitting for his portrait. I think he enjoyed playing the bourgeois hedonist, even though he’d founded an art school in an old convent and taught the hard labor of classic work from direct observation. He really was wearing a collared shirt and a necktie, as he worked, in the little film clip. His nickname was The Professor. Maybe I’m imagining it, but isn’t there a hint of amusement in his eye and the slight curl of his lip? It’s the look of someone who knows exactly what he wants. He did know what he wanted, and yet with each new effort he was still rediscovering what that actually meant. Everything he knew wasn’t enough. He had to surprise himself. It was always a beginning. His smile casts a long shadow.

Comments are currently closed.