Islamic art

I is an other. — Rimbaud

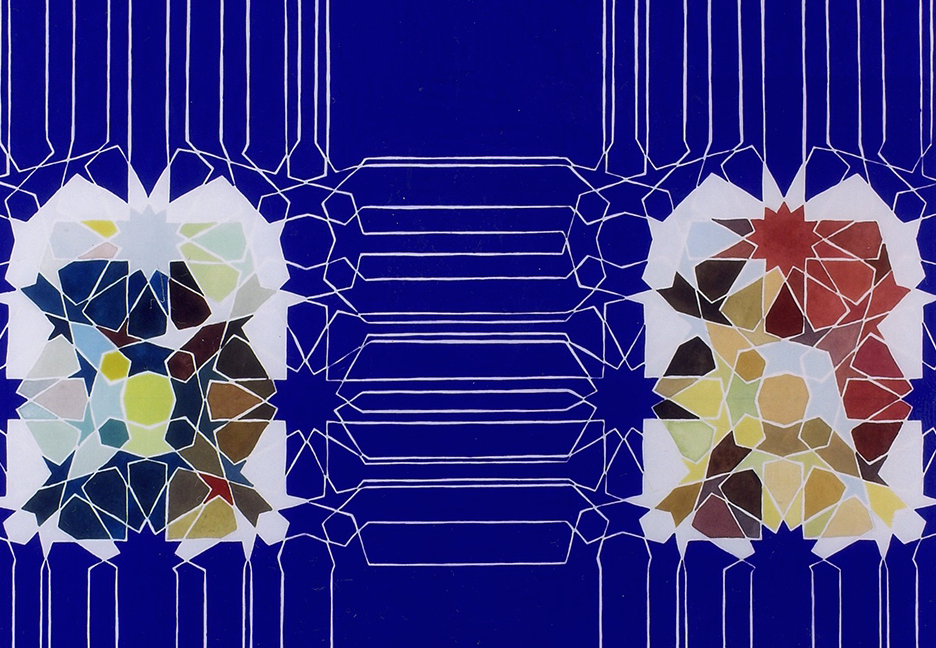

In my current re-immersion in Matisse, I’ve been reminded of how deeply he was influenced by the East, both in his Tangier sojourn, and in a journey he made to an historic exhibit of Islamic art in Munich, in 1910. He embraced the hedonism of sunny Tangier, but he was also moved by the peace and order of its religious imagery. He discovered the power of pattern–as a way to free himself from post-Impressionism, reaching for abstraction without completely surrendering to it, and he recognized how what may seem purely decorative can become laden with subtle meaning unavailable to the Western tradition, at least until the 20th century. The mathematics embodied in Islamic designs are assumed to be serendipitous anticipation of geometric insights developed in the 20th century, or were a visualization of math within Islamic intellectual culture (Persian society once considered science and mathematical exploration to be an integral, central part of human life). I’ve always been drawn the fractal patterns of Persian carpets my larger still lifes because of the suggestion that math and science are consistent with a vision of life as sacred. Braque and Burchfield rooted their work, as well, in decorative elements that bore far more meaning than mere ornament: Braque’s father had been a house painter, and he apprenticed early on with a master decorator–his ability to mimic various surfaces of marble, stucco, and wallpaper became crucial in his mature work where it gave the flat surface of a painting a timeless resonance, like a fossil record of daily life, far beyond its representational signifiers. Burchfield, as well, worked as a wallpaper designer, as a source of income, and his emphasis on patterns becomes one of the crucial ways he conveys forces of nature in his most original watercolors–summer insect sounds look like arabesques of rising smoke. In my Googling, I happened across this site of a contemporary artist also deeply influenced by Islamic art: Navine G. Khan Dossos, aka, Vanessa Hodgkinson. As it did for Matisse, Islamic art frees her to find color harmonies that would probably be unavailable in a more representational image, and the effect is musical. She relies on qualities of Islamic “decorative” design, but in a conceptual and more political way. I love the color and the self-effacing way it’s presented in regular grids–how individual expression surrenders the stage to the discipline of repetition and regularity. Echoes of Stella, and many others, as well as Mecca. And like Blake, she forsakes oil in favor of water-based paint, with an affection, similar to his, for the early and mid-Renaissance. For me, the effect seems closer to Byzantine mosaics.

Comments are currently closed.