Rediscovery

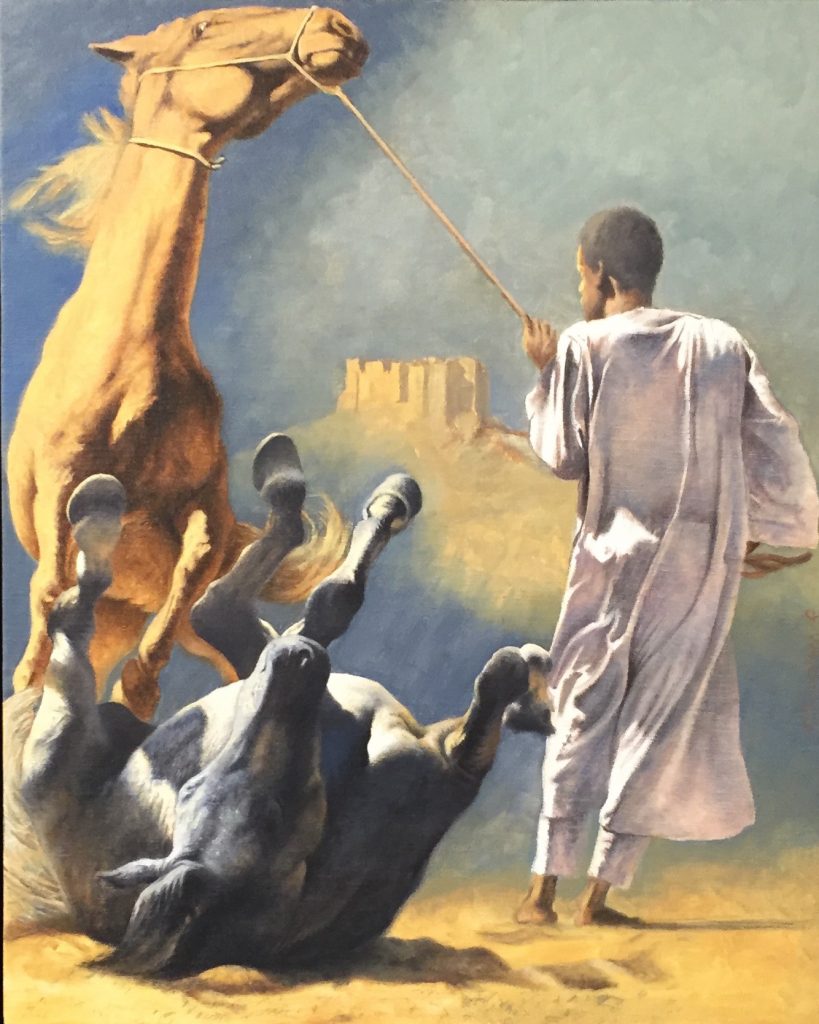

Study for Conversion of Saul, Tom Insalaco, oil on canvas

On Saturday, home for a week from Toronto, where I visited the Lawren Harris show at AGO, it struck me that I don’t need to drive three hours to see great art. If I make a point of getting out of my cave for a few hours, I can see dozens of great paintings, some astonishingly brilliant, with only a ten minute drive from my door. I remember when my parents moved to Pittsford, just outside Rochester, decades ago, and I was girding myself for my freshman year at the University of Rochester. Within weeks of our arrival, I visited our local museum, the Memorial Art Gallery, and was dumbfounded to realize that I lived only a few miles from a Rembrandt portrait. We’d moved here from the Northwest, and I’d been painting for three or four years at that point, and I’d never been to an art museum of any sort, and it was as if I’d stepped onto another planet, standing before that oil painting of a young man. Over the years–I moved away six years later and didn’t return to Rochester until another decade had passed–the collection at MAG has gotten deeper and richer. So on Saturday it was my middle stop between two other neighboring galleries, Makers Gallery and the home for my own work, Oxford Gallery, which has had an assortment of paintings and sculpture from gallery artists hanging throughout the summer. (The show ends in a couple weeks.) I got a glimpse of a full spectrum–a new, entrepreneurial space where local, exceptional emerging artists show their work, and then a museum that offers rare work from the most recent to centuries-old, and finally one of the area’s most established commercial galleries, still enduring with sporadic sales despite our endless economic stasis. It was gratifying, encouraging and energizing to see such great work in all of these distinctly different places.

At Maker’s, I got an early pre-reception glimpse–the show had just gone up–of work being given an encore from previous exhibits. It was all good, but I was especially impressed by some images on wood panels from Bill Stephens where he has taken paintings he’d put aside in the past and partially sanded them to reveal what amount to newly discovered and purely imaginary scenes. They evoke other worlds, mountains and seas from a crepuscular dream. They could be mythical landscapes viewed through isinglass. I’d seen Andrea Durfee’s landscapes at an earlier show there, but this time around I recognized more clearly how effective they are: geometrically vectorized scenes in which the lines define luxuriantly colored cells constructed into images that work as both representation and abstraction. To put it more directly: she can turn the human form into hills and hills into faceted gems.

Every time I visit MAG, I have the same feeling: a sense of startled gratitude for the intelligence behind its collection and the exhibits it pulls together, sometimes within severe constraints. When you walk into the exhibition space right now, you’ll find yourself spending half an hour in what would otherwise have been a foyer, but has been turned into an eclectic survey of portraiture. It offers an incredible range of work, from a portrait of John Ashbery by Elaine de Kooning to Kehinde Wiley to Sir Joshua Reynolds and a dazzling, effortlessly executed–did he ever make a false move?–oil from John Singer Sargent. What most impressed me about this show, aside from how the curators had leveraged the small, available space, was the way it worked for nearly anyone who spent time with it. Those with a deep knowledge of art would find gratifying surprises: a representational work from Elaine de Kooning, and not only that but an immediately recognizable likelness of a major American poet who happened to have been born here in Rochester. Yet a class of secondary students would be just as charmed by the work, and the carefully, accessibly worded descriptions of each painting. I’ll be posting examples of work I saw at MAG on Saturday, both from this show and from the permanent collection, all of which made me intensely grateful for having such easy access to such exhilarating work.

My final stop was also my longest, since whenever I visit Oxford, I end up having a cup of coffee and a two-hour conversation with Jim Hall on a dozen topics, in which I basically try to prompt him to amaze me with his knowledge of European and American history, Western art, philosophy, gardening, or politics. As we talked I kept focusing, as I’d done at both Makers and MAG, on work I’d seen before, but hadn’t fully recognized. I had a clear sightline to a small oil from Tom Insalaco, a preparatory study for his Conversion of Saul, a large painting indebted to Caravaggio that I’d seen in an earlier show. Somehow I’d overlooked this little study before, brightly lit, set in the desert, with two horses, one rearing up in protest and the other toppled to the ground, with a figure who looks both Bedouin and African. It’s a remarkable, dynamic image, a controlled exploration of how much can be done with a palette restricted to bluish/gray and gold, along with the stallion handler’s white thawb. In this little image, Tom has embedded multiple ironies. For one, there is no Saul. For another, as a whole, the image seems more a commentary on the Arab Spring than an exegesis of a Biblical parable. One horse has been toppled and another is rearing up, nearly out of control, and the ostensible handler is more bystander than active agent, exerting little control over what’s happening. In the distance, a structure that seems nearly swallowed up by a sandstorm. Insalaco’s work almost always has that fertile ambiguity, laden with multiple, sorrowful ironies about contemporary life, even when his subject is supposedly thousands of years old.

More to come from my visits on Saturday.

Comments are currently closed.