Painting as music

Fairfield Porter

It’s been a while since I last reread Keats. Yet I’ve always thought of his odes as the best example of the routinely remarkable synchronicity at the basis of traditional, rhyming poems. I like his famous odes as an example of this, because his two most familiar ones, on the Grecian urn and the nightingale are—at least for me—both wonderfully crafted orchestrations of sound and yet also perfectly, uniquely clear in what they mean. The beauty of their perceptions and ideas and imagery are expressed in words that also just happen to sound beautiful. What mystifies me is how the unique meaning captured by those particular words happens to rhyme in all the right places—it’s part of the wonder of poetry, how sound and meaning work together, though they would appear to be entirely unrelated. A Keats poem would sound enchanting, if spoken aloud, even to someone who doesn’t understand the language, and yet the music of those sounds has no rational connection to what the poem is saying. You couldn’t change a word without diminishing the ode; these are the only words in the only order Keats could have chosen to express what his poem means. So how is it that these words happen to rhyme in all the right places? At one level, the marvel of what these poems do is primarily sensory—it offers the purely physical pleasure of its sounds, the way they hit the eardrum, the way you imagine them humming in your own chest cavity as you read and silently recite the poem to yourself. It’s, at some level, a chant, which is far more about sound than meaning.

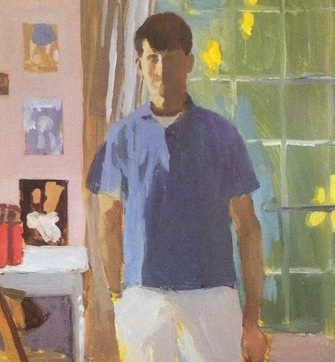

Something similar happens in the work of painters I love. I guess this is a long way to go to say that I favor Fairfield Porter probably more than any other American painter—and it’s largely because his work so perfectly illustrates this same duality. It’s both a way of creating a musical improvisation—the painter arranging color the way a poet composes pure sounds—and yet the orchestrated colors also happen to fall together in such a way that they show you an overlooked moment from daily life. On the one hand, the music, and on the other, the subject or “content” of the work. (I don’t think it’s an accident that many of Porter’s close friends were fairly well known poets in their day. He painted their portraits and tried his hand at poetry himself.) His work offers, for me, one of the finest examples of this duality you get in poetry, though in visual terms. Modernism made this possible, or at least it gave artists the motivation to create images that have this double life. It’s a long roll call of artists who were especially good at creating paintings that operated on both of these levels, as color became, for many of them, the actual point of the painting—Monet, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, Porter, Welliver, Thiebaud, Mattiasdottir, Fish, and countless lesser known artists over the past century and a half. In his best paintings, Vermeer anticipated all of this, setting up a scene and painting it in ways that focus on what color alone can express, while he’s also rendering a particular scene in a particular light. Rothko fits in here as well, since his subtle color consistently evokes the horizon line of landscape painting. Look at a Chuck Close from about a foot away and you’ll see nothing but a field of brilliantly colored oil paint, in grids, thickly applied, and then step back and the individual colors recede as the face comes into view, as if by accident. The work is pulling at you in two different ways, as a gorgeous physical object and also as a window through which to see what the artist saw. The “meaning” of these paintings resides in the vitality created by the tension between what you see and what you’re really getting: the physical, sensory pleasure of all that painted color and the marvel of how it all comes together in an imaginary image you recognize, both because of the color and sometimes in spite of it.

You come dangerously close to assigning meaning to paintings, or so it seemed to me, unless poems don’t mean anything either.

The danger of meaning! That’s funny, but that’s just about right. I meant subject, rather than meaning: poems and paintings both have subjects and they also create a tension between two different kinds of perception. You hear the sound of a poem and understand the words at the same time, and with a painting, you both see the paint and see through the paint to recognize something that isn’t actually there. The great paintings work at both levels: giving you something that works on both the senses, as a kind of visual music, and the imagination, which sees an image beyond the painting, as it were. For me, the sensory quality of an image is at least as important as the subject and sometimes far more lasting and valuable. It’s what survives long after the subject means little to those who look at the work. I’m not all that interested in the Spanish domination of the Low Countries centuries ago, but I love looking at Brueghel’s painting of the Duke of Alba coming down the mountain to torment his subjects–and my appreciation is about the quality of the painting, as a painting, not what it’s “about.”