The bait and switch

I’ve been brooding for a long time about something I keep running up against: how highly intelligent people I know, highly educated people, who enjoy both art and photography and have sophisticated taste, cannot see anything to like in much of what’s been considered great in art over the past century. What many of us consider virtually classic, if classic can include both Picasso and Vermeer, leaves these people shaking their heads with puzzlement. They shrug when they see almost any kind of abstraction. Tom Wolfe took this same stance when he wrote The Painted Word, in which he suggested that abstract expressionism was little more than an illustration for Clement Greenberg’s theories. It was, in his terms, a way of putting Greenberg’s words into paint. The AbEx painters were simply showing, in visual terms, what he’d already said in his criticism. Wolfe celebrated photo realism as a return to sanity, and as much as I enjoy photo realism, it seems a little anti-climactic as a victory of sanity over madness, coming at the end of Wolfe’s typically over-the-top screed. Yet I find myself sympathizing with these reactionaries, who serve as a warning about what just doesn’t feel right in so much work that passes for great. The quote from Peter Schjeldahl I posted a while back echoes this unease about what’s happened to art, at least since the 60s: “The sixties had begun in a spirit of clarity, with youthful embraces of democratic taste and pragmatic joy. Then the shock of so much change, so fast, set in. As the art world expanded, it also fragmented, and artists retreated into subcultural parishes. Today, it seems plausible to look back on the past three decades in art as one long case of post-traumatic stress.” What’s interesting is that someone who may be our greatest living art critic finds himself as dubious as the next guy about what has been happening to art–along with great critics like Roberta Smith and Donald Kuspit–and the only point of difference is in how to assign the date when things started to go awry.

The puzzlement of some intelligent art lovers when they look at a Rothko makes me wonder if I’ve simply had a bit too much of the Kool Aid over the years. I refuse to believe it. I see the beauty and simplicity of his images, and the gravity of his devotion to art, and with a little study, I think maybe these dubious friends (including family members) would see it too. But I find myself reacting, involuntarily, the way they do, to a lot of work that has been celebrated as “important.” To wit, my reaction to Ed Ruscha’s word images, even though his enormous still lifes of trash strike me as powerful and elegant. Lisa Yuskavage’s coy duplicity about her subject matter puts me off, even though I love her handling of paint, and what I think is an honest and skillful passion for color. It isn’t simply that I’m annoyed by the knowing smirk I detect behind work like this, it’s that this professional smirk brings such high prices and seems to enable the art world to operate like one of those exclusive trading floors a little further south of Chelsea. Some level of cynical irony seems to be a cornerstone of how the art business churns the revenue of its one-percenters. (Here is where one usually points out that it was no accident that Jeff Koons was a stock broker before he became an artist. So there you go. Cheap shot, but he’s too rich to care about what anybody says.) I kept brooding about this all morning until I realized the way to describe my reaction to “great” contemporary art that leaves me cold is that I don’t trust it. Yes, I know, art is fundamentally untrustworthy. I think Dave Hickey has written at some length about how fungible the notion of authenticity is when it comes to visual art, and this is partly what enables it to survive and keep offering new meaning to succeeding generations. It’s meant to seduce you, not be true to you: that’s pretty much the foundation of his critical stance and you have to celebrate anybody who wants art to bring pleasure and then explain to you how this pleasure can be an ark for meaning. But Chardin seduces me and earns my trust at the same time. That cluster of grapes is exactly what he’s showing me. William Blake I trust because he was so honest he couldn’t say a thing without making enemies: The nakedness of woman is the glory of God. You said it, Bill, and you painted plenty of naked bodies to prove it. But what would you have thought of John Currin? And why does Currin’s work feel like a con to me? I can’t explain it myself, but I don’t trust it.

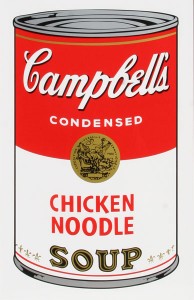

The artists I love don’t hold out a teapot to me and then, when I take hold of it, say, “Punked! It’s full of hazardous waste, you fool!” So much of what has passed for art, starting with Duchamp, seems to work this way. Either it’s supposed to look like junk, but really be a thing of beauty, or vice versa. Either way, somebody is putting you on, widening the gap between appearance and reality. That’s pretty much the definition of a lie. Art is trickery, from the start. Always has been. Always will be. It’s only paint, and it makes you see things that aren’t there. True that. Yet I will testify that Campbell’s chicken soup has curative powers. It’s one of the great comforts of life. It isn’t as good for me as the soup we make in a stock pot here at Casa Dorsey, but it gets rid of a cold much faster. Perservatives? No doubt. Too much salt? No doubt. But I swear by it. Maybe that does make me a fool who doesn’t care about what’s really in that red and white can. Yet Warhol’s flattened image of a Campbell’s soup can makes me wonder if he’s showing me a simple, small comfort that has helped me get through some of my worst days, or if he’s mocking middle class American consumer culture, as if to say, Here you go, fool. Eat this. I don’t trust him.

Thiebaud I trust. Dine I trust. Maybe that really does make me a fool, since it’s all a trick anyway, right? Technically maybe so, but what gets conveyed doesn’t have to be tricky. The only thing that distinguishes me from the people who don’t love Rothko is that I see, and feel, how much genuine passion he put into his images–and I don’t know why I see that and others don’t. Clement Greenberg couldn’t have justified Rothko’s work that way—hey, check it, look how much he loves his color!—but it goes a long way toward explaining why someone could love Rothko and be left cold by Duchamp and all his heirs. The problem continues to be, how do you get someone to see the love Rothko put into his paint? And am I just being blind to what’s inherent in the work of big names that leave me cold? It’s the question that still hangs over the past hundred years, a question that nobody can answer in a convincing way, and it makes me wonder how much I’ve been talking myself into liking things that aren’t going to last. But then I suppose “liking things that don’t last” is pretty much what so much of life is about, as you watch each year pass a little faster than the one before it.

Comments are currently closed.