Iluminations of illuminations

Sweet Kate, In for Repairs, Ray Hassard, oil on canvas

I came away from the current show at Oxford Gallery craving more excellent oils from Ray Hassard. His pastels are masterful and the latest work he’s been doing in Florida may be better than anything he’s done in the past: the way he captures the light so that it gives a sense of depth and even immense volume to the space in these small landscapes is remarkable. Yet, maybe because I’m an oil painter, my favorites are the oils in the current Oxford show. Like a number of other Oxford artists—Chris Baker and Matt Klos—he’s fascinated by the most commonplace scenes. Beyond the immediate pleasure offered by the color and the play of light and shadow, he conveys a sense of completion and harmony in scenes that invites you to look again, in a fresh way, as if for the first time at scenes you otherwise might not even notice. Hassard picks the least auspicious subjects: a leftover holiday decoration on New Year’s Day, a crossing guard brandishing a stop sign, or someone nearly lost in shadow cleaning and repairing an old boat in storage. My favorite painting of Hassard’s was in a previous show at Oxford, a small image of a parked pickup truck, a view one could enjoy of thousands of trucks parked in small towns and villages anywhere in dozens of states—and you would never give any of them a second look if you passed them on the way to somewhere else. The light, the color, and the abbreviated rendering with assured brushwork—he could have done the painting in a single sitting, en plein air—concentrate energy and a sense of ease in Hassard’s execution. Bill Santelli and Bill Stephens joined me at Oxford to see the new work and Santelli pointed out how Hassard again and again composes an image, like Diebenkorn, so that smaller areas of comparatively intense activity are clustered close to a top edge, with a more uniform expanse of color beneath it—a field, a floor—creating a tension between the complexity of form against an open void below it. Hassard’s real subject is the unity and uniformity of the light, rather than anything it reveals in particular. My favorite in this show is Sweet Kate, In For Repairs, his view of an old boat maybe being readied for another launch. It’s actually one of his least colorful, a field of neutral tones with a few small notes of muted orange, blue, green and a tiny stripe of red. In the foreground: a trash barrel with a loose load of scrap jutting out in all directions like a month-old bouquet, and a narrow, tall pylon. All the activity he depicts, the subject of the work, is just visible, pushed to the background, half-hidden in shadow. The worker, up on a ladder, is barely indicated, perfectly done, with a few patches of color, tucked away, almost out of view, like an Easter egg. The light is modulated gently throughout the entire scene, and even the higher reaches of the repair shop are dark but still dimly illuminated, with the darkest shadow reserved for small pockets of space under the boat. You feel the day, the season, a world in which the boat repair is neither more nor less interesting than the trash in the barrel—it’s all good and essential to the whole.

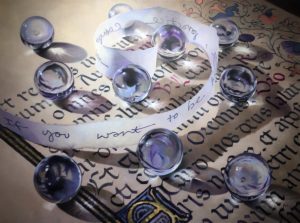

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.

Comments are currently closed.