Stop moving

Jim Mott paid a visit last week and we talked for a couple hours, as he sat in one of our Adirondack chairs and sketched a bit of what he saw in the yard, probably some of the birds attracted to our feeders. He was wearing a Red Sox cap someone had left in his car once, and was in a good mood, thanks to the fact that he has a job working with a nature conservation group to supplement whatever he makes from his art. Most of the time, Jim trades his paintings for room and board, when he’s in his Itinerant Artist mode, but he also sells and has a show coming up with several other regional artists. It was a good conversation, and here is some of it:

JM: On those rare cases when I sit down and really draw something it’s so refreshing but it’s hard to make myself do it. I do a sketch and think maybe I’ll do a painting from it and then I see everyone else holding up their phone cameras. Working from sketches, we’d be doing art the way we did it thirty or forty years ago. Richter certainly relies on photography.

DD: Richter’s name has come up a lot in the past few days. I was just emailing with Rick Harrington who was talking about how he’s been watching Richter’s videos. And I was emailing this morning with Bill Stephens and Bill Santelli and we were talking a little about Richter.

He does those big squeegee paintings which I really like.

I do too.

I saw some of his photo-real paintings in Chicago.

We talked about that.

Up close the presence of the paint is so sublime.

I think he focuses a lot on the quality of the surface. I think he’s looking to Vermeer and Old Masters for the photorealistic paintings. He gets that very soft edge.

But what makes the paint feel so there is that there’s such a sense of material. Its like the feel of something done with limestone.

Rick and I have talked about our disappointment with Walton Ford’s paint. You stand back and it’s one hell of an image and it really works, but the love of the paint doesn’t seem to be there. You can see the paint and it’s very evident; it’s a jumble of paint up close but it doesn’t have that quality you’re talking about. But it works.

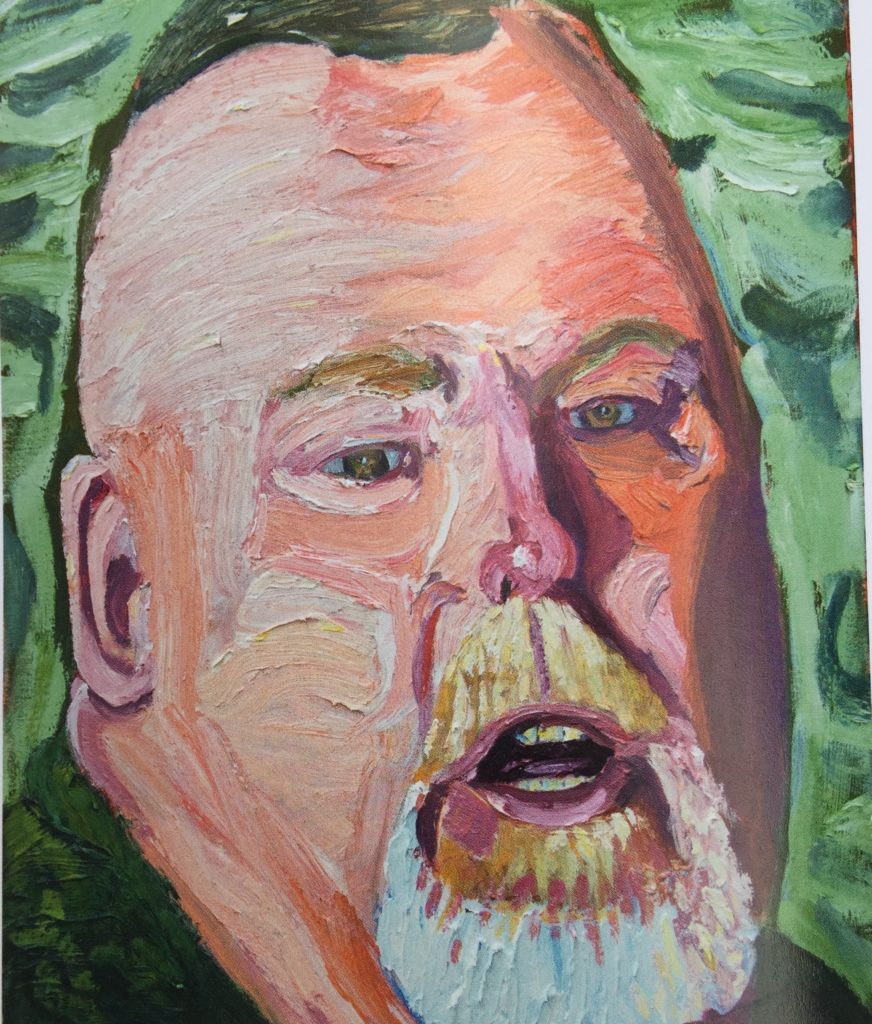

This is a distraction but you’ve probably seen this book. (Jim handed me a coffee table book he’d brought with him, a catalog of George W. Bush’s portraits of war veterans.)

No. Oh, Bush. Oh, those are good! Those are better than I thought. Huh. Good for him.

It’s such a bizarre thing.

Well, Churchill.

But he’d never painted before. There’s a strong sense in my mind that he’s doing it as a kind of atonement, but it’s cheerful.

It reminds me of Philip Burke.

After he started to paint he started to notice that shadows weren’t shadows but colors.

These are way better than I thought.

He said, “I became comfortable with the idea of tones and values.” Wow.

This one, he’s just pushed that so far that it’s interesting. It’s like Lucien Freud.

Freud is one of his models. You’ve got a president who started war and now is painting. These are all guys who have come to his treatment center. Damaged.

We were going to talk about social media vs. painting.

I used to focus more on social media as a horrible thing. It’s fun to get likes and so on, but it takes you away from yourself. I was thinking about digital photography, the way everyone depends on it to process the world. You see people holding up their phones everywhere.

I depend on digital photography for my work. But social media is turning it into a stream of sensations. I can’t tell if my A.D.D. is age or because I’m media-saturated. But you probably aren’t as exposed to media.

If I go on Facebook, I’ll be off in a minute or I’ll be lost for an hour or two. I don’t go on more than every few months.

I post pro forma stuff. I’m not using Facebook at all. It’s just a sign that I’m still here. There is something good about it. Nancy uses it with more personal interest than I do. It really keeps her in touch.

If I put in any amount of time I feel so thin and out of touch with . . . meaning. My wife writes really well and does beautiful posts and she designs them to be liked and they are liked. It’s hard to say. I’m naturally resistant to change and a little bit of a Luddite but a painter I admire said I was her favorite painter, but other than that the things I like are talking face to face or wandering at night in the city and being surprised by effects of shadows. Social media, it’s kind of like drugs. I remember hearing one of the Rolling Stones say that it all depended on whether you can handle it.

Had to be Keith.

Social media, if you can handle it sure.

Nobody is talking about painting as a counterforce to contemporary media. It really is. It’s a still, focused activity.

It’s working with real material.

The physical world.

My philosophical orientation is that spiritual growth comes through working with your material. You are a material thing. You work with it. Dematerialization isn’t spiritual.

Disembodied. That’s interesting. That’s Matthew Crawford’s view. He wrote those two phenomenal books. He’s essentially a philosopher, became a motorcycle repairman. He’s a phenomenal writer. That’s what he’s exploring, the nature of physical awareness and intelligence. That is what gives you a glimpse of something more, or what seems to be more. The subject of spirituality, the spiritual dimension of art—it’s such an overused term—is something I’ve been wanting to write more about. For me it has to do with the limitations of the conscious mind. It’s complicated.

It is. But rich, though.

For me, it all has to do with gaining some kind of humble perspective on the nature of your conscious mind. That’s the crux of it. When you are able at some point to realize that your mind is constantly misleading you because you are so focused, this ability to shut out almost everything but what you are paying attention to. That’s the problem. Painting doesn’t actually eliminate that, it intensifies it, because you are paying attention to very small things and screening everything else out, but in the end you create something that has the ability to convey something larger. You get a glimpse of wholeness. That’s psychological, though I think of it as spiritual, but maybe that’s a meaningless distinction.

Say more.

Hmm. It’s funny that I went through a period in my teens where I had a very nihilistic period. It wasn’t voluntary or angry or a response to what I was going through in a conscious way, that I was rejecting all values as some kind of choice. It was the classic existential crisis in a way: the impossibility of meaning, any kind of fixed or absolute meaning. It was a sudden certainty about the impossibility of meaning. I struggled with that for years until I had an insight that this was my individual mind that was putting me in this box, not necessarily the nature of things. Even if I couldn’t imagine meaning didn’t mean it wasn’t there. That was like turning a corner, or completely turning around: the sense of of course, how could I not have realized this?

Some philosophers might go the other way and say, everyone wants meaning but they aren’t open to the reality that there is no meaning.

Yes. The total opposite. Postmodernists you mean. It came from reading Kierkegaard. The Sickness Unto Death. He was saying that despair doesn’t know it’s despair. Despair hides itself from itself. It’s like denial in the recovery movement: he was describing something like that; you think you know what’s happening but you don’t. Being in that state hides itself from you. That was something that had never occurred to me. I’m in this state, and I don’t know it because I’m in that state. For Kierkegaard, we are all in that state, everyone. The only way out of that state is not through your own effort, because any effort arises from the state you are already in. Any effort to construct meaning arises out of this ignorance of the state of your own consciousness. I started painting in this period, not thinking that it had any meaning, but because it was an instinctive response to this lack of meaning. Then I began to see that maybe this activity was a way of grappling with this, a way of reaching out for meaning without thinking it’s possible or having to know what it is. Everyone is such a positivist. Everyone has to be so certain about everything. I’m uncertain about everything, and I’m totally comfortable with that. Uncertainty is the nature of things. The certainty isn’t what counts. It’s the sense that you can have faith in a meaning you can’t grasp.

I’ve been listening to this learning series, great works of English literature. This nice English man has this line I can’t remember where he keeps going back to the Romantics, Wordsworth and Coleridge. He talks about meaning that can’t be rationally explained or grasped, but can somehow be glimpsed now and then. I like that. I was thinking about doing night sketching and why I’m drawn to that, and I guess it’s why someone is drawn to painting in general. It goes back to Kierkegaard’s phrase about being transparently grounded in the absolute. In college that was my favorite phrase from him, because it seems so cool. That’s what’s happening in the art process.

You become transparent to what is happening in the process, what’s being conveyed, without your intending to convey it or knowing what you are conveying in a conscious way. You’re not putting it in there. You’re the window that lets it come into the work.

He calls it the absolute; you call it a glimpse of wholeness.

All of this is so contrary to what everyone thinks when they think about the art world now.

I’ve internalized a lot of art history, but whenever I write an art statement I’m always drawing from literature or the Bible, even though I’m not really religious, or from philosophy. It’s always this other realm of people trying to figure stuff out, poetically related to that unknown, which is meaningful.

I’m constantly seeing things in literature or philosophy that have more to do with art than most of what gets written about art. What some novelist has said, or whatever, and how that reflects the process of painting or what goes into a painting.

The writer or painter or theologian are all after the same thing: to make sense of all this.

The craving for meaning. Wittgenstein would say that what you’re asking for is so nebulous . . what you’re pursing doesn’t exist. Your mind craving something because of a confusion that arises from language. I’m not really sure that’s actually what he felt.

So much of the talking and thinking about meaning, a little of that and I go away feeling empty.

Right. That is the point. As soon as you consciously pursue this thing, you have this . . . this need for what it is we’re talking about, but as soon as you start focusing on it, defining it, it disappears. It can’t be an object of conscious pursuit, but it can be there in the pursuit.

One of my most positive art experiences was the year before I started the itinerant project, I went to Provence and lived with this family. Landing in France and taking this train to their town, I was overwhelmed by doubt and lack of confidence and sort of swimming or drowning. But I started sketching out of habit. I started to feel connected and feel good and just by making these little marks that showed mountains and trees. You like Ai Weiwei.

Yes. I follow him on Instagram.

His work can be political but it’s more.

Yes, it exceeds the metaphor. The intent. It goes back to desire. This is where I agree with Donald Kuspit in Idiosyncratic Identities. It has to come from eagerness, desire. You can’t say I’m going to do this to have an impact, a social impact. I’m going to be a social justice warrior and make art so that life gets better and so on. That’s one way of intentionally choosing: the other is to do something you don’t want to do in order to sell. But if it’s physically enjoyable and fulfilling somehow, it’s alive. The only way to make it alive is to blindly do what you really want to do. You do that. You paint exactly the way you want to paint. This is the way you respond to what you see. It’s the way you make a painting.

The Itinerant Artist Project arose as something I felt the need to do. If I analyze it I could market it better for its relevance.

I don’t see a problem with that.

But then I think what can I do differently, what can I do next. I don’t really love painting.

You say that. I feel the same way. The anxiety before you start painting.

I don’t really know what to do sometimes, but I feel better once I’ve done it.

I often don’t want to sit down and paint, but as soon as I do, I’m into it. Being done is the best part. It’s satisfying seeing it emerge. It’s a balance between the tedium of the labor and the satisfaction of seeing it done which is continuous.

The day I accepted my job I went to the studio and started doing black and white and gray marks in conversation with one another and it was something I wanted to try. I hadn’t been able to do a painting in a long session for a long time but I did some of these for days. I didn’t care if anyone else got anything out of them because I had a job now. The element of . . .

. . . not having to get results . . .

Right, it was just a process.

It’s all about process for me in two different ways. One is I have a technique, a method now and get the results I want by sticking to a certain process. There are surprises and I’m always improvising along the way. But the other work I started earlier this year are these small paintings of bowls, looser, less detailed and faster and it’s much more about the freshness of the paint. Like premier coup. I did maybe six and one I felt was the best got into two shoes. It’s in North Dakota now. When I did them I thought these probably won’t get into shows or sell. But that hasn’t been true.

You really wanted to do it.

Exactly. I forgot about productivity and sales and shows and yet the response was there. I’m going to alternate between the two modes, very realistic and this new way forward. For years and years I had given up mostly on that path.

I’d like to find a path. I have so many that are just one or two but I can’t do it again.

In this recent effort there were two or three that really succeeded out of eight. The others were good, but they weren’t what I was trying to do. They may have succeeded in a way I didn’t intend or understand.

How do you connect with people? The question is how do you reach people.

My attitude is that you put it out there and if they find it, great. If they don’t, that’s fine.

My parents were activists so I always have the sense that if something’s wrong you have a movement.

I guess so. I can see that. I can see that with a smile. Like, Stop Moving. The Stop Moving Movement.

I’m going to steal that. That’s great.

Enough with the moving images.

I’m in a show in August at Main Street Arts in Clifton Springs.

It’s a great gallery.

I’ll be in a group show. A couple people are really good and they sell a lot. I have a lot of work still to do for it.

I’d be interested in seeing the abstracts you’ve been doing.

I really like them, but when I put my glasses on yesterday, a month later, I realized they weren’t as good as I thought.

That’s often the case with anything.

I don’t feel that “landscape painter” captures much of what I’m about. These black and white ones put me all over the place. For the show, there are so many paintings I want to do.

How many do you have to do?

He just wants little ones. I imagine if I can do ten or twenty that would nice. I’ve only done one that I like so far.

You could do twenty in a month. Are these all from life? Do you take photos?

Sketches and photos.

Comments are currently closed.