Thiebaud, part 1

Art history in its essence is an organic, growing, and changing discipline. It’s more like a private game refuge, a treasure of exotic and wonderful rare Art Beasts. And our interests continue to change as we find out more and more. It’s hard for me to recognize something like progress or evolutionary development, say in a Darwinian sense, in the development of art. For instance, though I’ve conscientiously studied his paintings for many years, I just can’t find anything new, conceptually, in Paul Cezanne. For me he’s just a damn good painter, who’s using practically every device, convention, and trick in a painting, but he was so terrific, so bright, so careful in trying to be true to his relationships, that the painting is different, not because of any invention, despite his beliefs, but because of the composite structure and complexity of his perceptions translated into paintings.

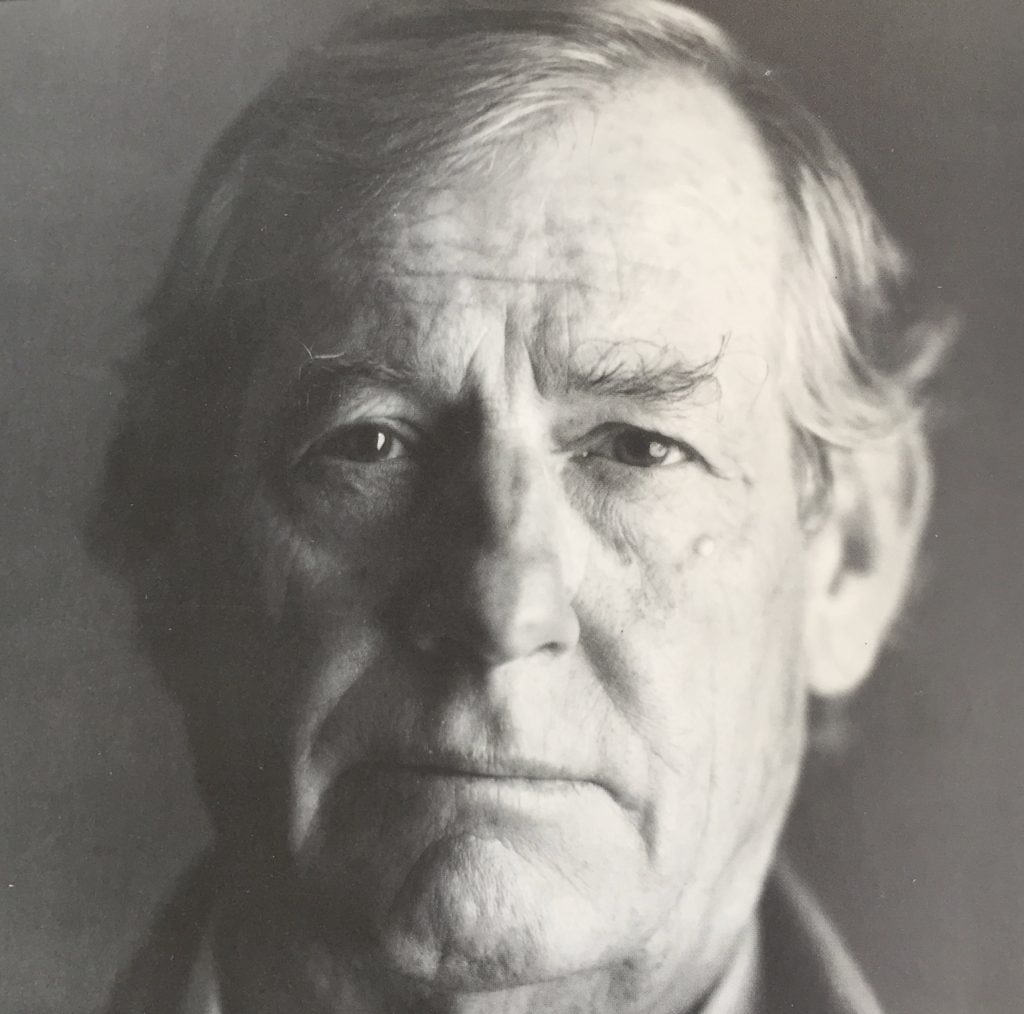

–Wayne Thiebaud, from Art of the Real, edit. Mark Strand, Robert Hughes forward, Clarkson N. Potter, New York, 1983

In the fewest possible words, and his typically humble voice, Wayne Thiebaud here says nearly everything an artist needs to know about his or her relevance at any given place or time in the world of art. To wit: the historical sense of place and time don’t matter now. Everything is permitted; but only a few things are worthwhile. Thiebaud came to this realization after Arthur Danto did, but before Danto started talking much about it in 1995. By the 60s, when Thiebaud emerged by being mistakenly classified as a Pop artist, it became possible to do anything and call it art. There were no longer any limitations on what could be considered a work of art, something Duchamp asserted decades before, but it was a cynical declaration of freedom that didn’t flourish until the Pop artists adopted that same philosophical stance and liberated artists to do whatever they wished. The ironies embedded in Pop’s appropriations struck Danto as an integral part of the game, I think, but irony isn’t required and if anything it cheapens much of Pop and makes it far less interesting than it ought to be. (Don’t forget that Pop gave us Jim Dine.) It’s now entirely possible to paint like an Old Master without a postmodern smirk (some of Richter for example)—because the work has the same power now as it did hundreds of years ago. What Thiebaud is trying to say, and which remains difficult to articulate clearly, is that an authentic individuality matters more than any other consideration in art—and this individuality is infused into a painting subconsciously, not by choice. It’s about style, not stylization, as Susan Sontag said. Style is involuntary. A painting needs to be an extension, a replication not necessarily of something seen but of the wholeness of a painter’s identity, “the composite structure and complexity of his perceptions translated into paintings.” It has nothing to do with conceptual justifications or ideas or meanings and messages. A painting is more like a sacrament, a host for the life of the painter, than an expression of something a painter simply thinks up. It isn’t about thought, and it isn’t about hewing to anything but what an individual’s need to paint requires, which is something to be learned anew with each painting, something felt rather than known, discovered through act and instinct and a physical struggle with the qualities of paint.

Comments are currently closed.