The crucial thing is enjoyment

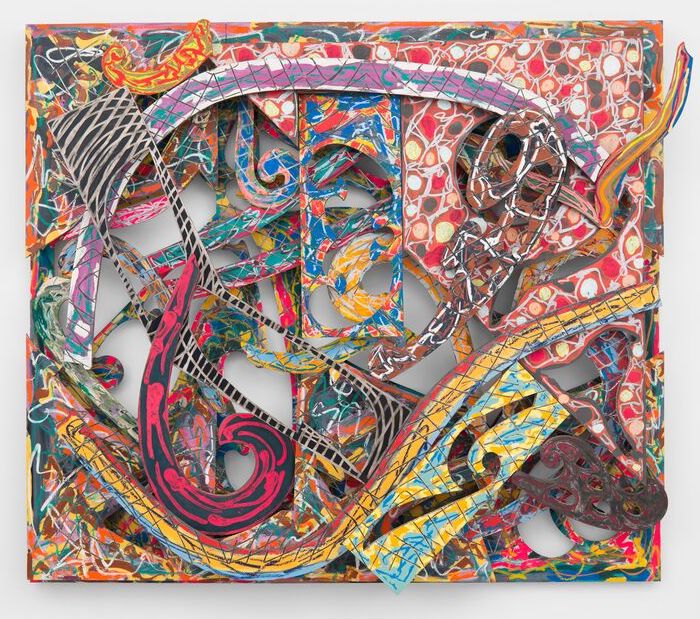

Frank Stella, Mosport 4.75x (1982), © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I couldn’t have put this any better, from the beginning of an essay by Robert Linsley a few years ago on the occasion of a Stella retrospective in Europe. My only quibble is that I’m not sure I see any intellectual side to Stella’s best work (one reason I love it), which Lindsay seems to suggest in a paradoxical way further on, when he talks about feeling the artist behind the work without any conceptual screen between viewer and artist. Art is immediate, even though it can take years coming back to it to actually see and feel a painting directly, and this passage bears that out even though it starts inauspiciously with critic-speak about “voiding of the subjective” while then offering the counterpoint of “feel the artist behind the decisions,” which is what he’s really describing:

I’ve enjoyed Frank Stella’s art since my own beginning as an artist, and the crucial thing has been the enjoyment. The intellectual or theoretical side was always evident—the literalness or factuality, the deliberate voiding of the subjective—and I never needed to take a course or read a tract to feel its necessity or reason, but overriding for me was the pleasure that accompanied the fact that I could also feel the artist behind the decisions. I had a particular affection for the Protractors, although it was many years before I saw one of the original Black Paintings in person, and felt how strongly emotional and romantic they are. I find myself thinking back to those early days in art because recently I’ve acquired a real love for Stella’s Moby Dick series. . . I’ve known about them since they were made, in the late eighties, and always thought they were an important group of works, but only very lately have I really seen them, with a return to feelings about art that perhaps one only has when young. Inspiration means an intake of breath—the breath of life, being whatever one needs and wants to find in art. For me, Picasso, Matisse, Cézanne, and intermittently many others, were truly inspiring—they filled me with a sense of the possibilities of life. Emulation was the necessary beginning, but eventually I had to meet the challenge that was presented, to breath out and keep on breathing. In those days I drank in their work and always had a thirst for more, or, to return to the metaphor of inspiration, the fresh air of art brought every cell to life. Looking at art books was a daily pleasure that gave a perspective on the ordinary dullness of life; visits to museums were transformative. Every contact with art sent me back to the studio. I never had a “disinterested” response to beauty, for me it was always about what could be done—what had been done and what I could do, and every historical achievement was another possible path forward. This practical, achievement oriented attitude is why I like Stella’s writing, which is exactly that way, but I never expected to have such strong feelings about his work. Today I just want to stand beside the Moby Dick reliefs and feel the energy. It’s the unexpectedness of this response that, for me, proves its truth.

Comments are currently closed.