Minute particulars

He who would do good to another must do it in Minute Particulars.

General Good is the plea of the scoundrel, hypocrite, and flatterer;

For Art and Science cannot exist but in minutely organized Particulars,

And not in generalizing Demonstrations of the Rational Power . . .

-William Blake

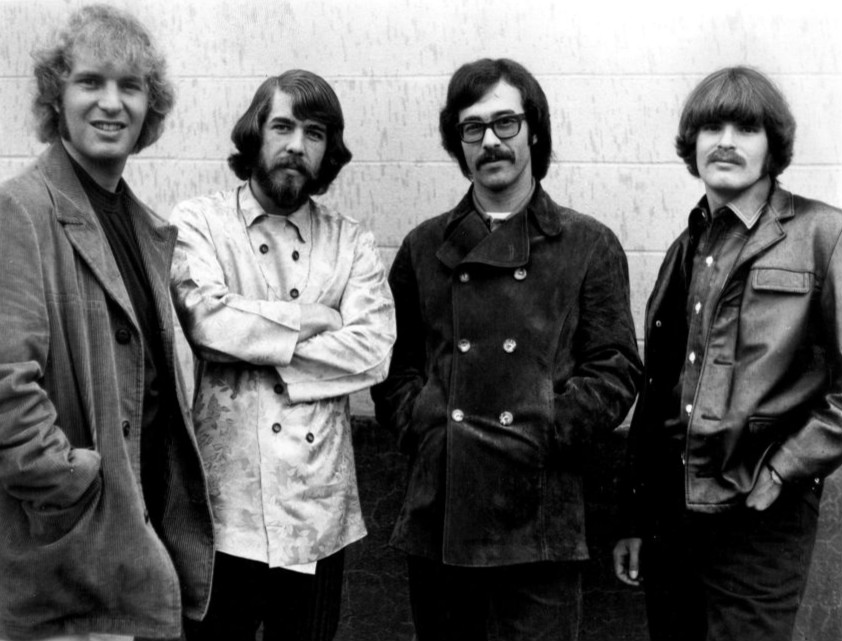

In the passage below, I think Jeff Blehar’s question was getting at something crucial when it comes to any art. It was from a podcast in which three political journalists took off their current affairs hats and spent some time talking about what they really love—music. In particular, Blehar was marveling at the sound of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Green River. He’s really speaking about all the tiny incremental “minute particulars” that go into any band’s unique mature sound. I was struck by his comment because I had a similar thought listening to “Bootleg,” the second song on another of the band’s albums, where, when the bass comes in, suddenly their sound surfaces—an illusion of looseness, the casual way the four instruments seem to lope along, in no great rush to get the job done, and come together as if by accident, two of them riding on the bus just jamming, waiting for the bus to stop and pick up the other two. The way its elements converge make any great work of art unique and individual in a way that’s impossible to duplicate or even describe clearly—and I don’t think it’s something that could be translated into a set of reliable algorithms. In other words you can’t learn how to do it repeatedly—you end up imitating pieces and parts, but not the whole. You can copy a Vermeer, but it won’t be a Vermeer. The jury will be out for a while on whether a computer could create a convincing Vermeer forgery, but I doubt that it ever will. Blehar says:

This is one of the things that gets lost but you hear it in everything they did. It’s that sound. Green River is the best embodiment of the band’s sound. That sound . . . every time they could just walk in and create a song that sounded good, like ear candy, something about the way Fogerty’s guitar, and his brother’s rhythm guitar and the bass and the drums came together on an elemental level is fundamentally satisfying. I guess I’ve never understood why nobody else can reproduce this. Why doesn’t every band try to sound like CCR on Green River? It shouldn’t be hard to do in theory. This is not Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It’s four guys in a room. There isn’t even much over dubbing. But nobody has ever sounded like that. It’s such a remarkable achievement. And it gets neglected because you don’t even notice it. They are so good at it, they draw you away from one of their primary virtues by making it seem so effortless.

What’s distinctive is how minimal CCR kept things, like the earlier Spoon, the simplicity in their production and instrumentation, but I don’t think any of that was a conscious choice. After ten years of work, the band had a perfectly realized style—in Susan Sontag’s sense of style, as unconscious and fundamental, not a calculated choice, not stylization. The style was who they were, something they arrived at involuntarily, an act of discovery, not the outcome of calculation. CCR wasn’t trying to sound like itself. It couldn’t help it. It was groping its way toward the supple, funky momentum of this particular song, and succeeded, by feel, not really knowing in advance how to do it in a reliable way—though they certainly seemed to find a magic formula for an explosion of creativity in a mere two years. In some ways, an artist can’t even recognize the qualities that make his or her work most interesting and individual. The fragrance that’s always there in the room eventually isn’t even noticed: we’re all too close to ourselves to even recognize our own genuine strengths and flaws. They had certain aims and their songs would evolve the way any creative act evolves, within its own internal, instinctive boundaries—but that instantly recognizable sound was a byproduct, not the conscious goal. The conscious goal was to make irresistible music by any means possible (isn’t that always the point, and if not, shouldn’t it be? I’m talking to you, Parquet Courts) and they ended up doing it the only way they could. What resulted was individually unique, in a way that even CCR probably couldn’t explain—and maybe not even recognize as clearly as someone who hadn’t created it—even if it had its roots in certain general genres of music, the tropes of country and blues.

This is part of the problem with categorization of artists. For example, to say that Thiebaud and Hockney and Warhol are all Pop artists is to say almost nothing, because it lumps three unique and distinctly different artists, with completely distinct aesthetic aims—and results—under a single rubric that does little more than identify the decade in which they emerged or maybe suggest that they were simply popular and more accessible to the general public than most 20th century artists. The same is true if you pick artists classifiable as photorealists: Chuck Close, Gerhard Richter, James Valerio and Antonio Lopez Garcia. Their work, to one degree or another, relies on photography as a source, but what else do they really have in common? According to Hockney, photo-realism, in the sense of using a lens to project an image onto a surface for tracing, goes back centuries and is embedded in Western painting as a kind of trade secret. Which means that calling someone a photo-realist conveys almost nothing about what a particular artist is up to in his or her work. The persistence of grouping artists into particular schools—both John Currin and El Greco can be called mannerists—conveys little or nothing about what the work actually communicates to a viewer, which has less to do with history and membership in a movement or school or general way of painting and much more to do with what makes a person an individual.

Comments are currently closed.