Things being just what they are

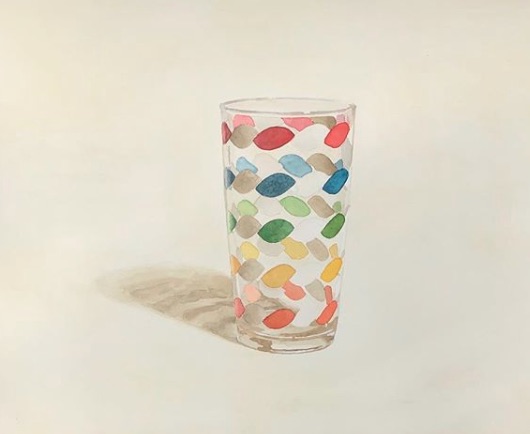

Optimistic Tumbler, Joshua Huyser, Watercolor, 2018

Mrs. Glass had undressed the package and now stood reading the fine print on the back of a carton of toothpaste. “Just kindly button that lip of yours,” she said, rather absently. She went over to the medicine cabinet. It was stationed above the washbowl, against the wall. She opened its mirror-faced door and surveyed the congested shelves with the eye–or, rather, the masterly squint–of a dedicated medicine-cabinet gardener. Before her, in overly luxuriant rows, was a host, so to speak, of golden pharmaceuticals, plus a few technically less indigenous whatnots. The shelves bore iodine, Mercurochrome, vitamin capsules, dental floss, aspirin, Anacin, Bufferin, Argyrol, Musterole, Ex-Lax, Milk of Magnesia, Sal Hepatica, Aspergum, two Gillette razors, one Schick Injector razor, two tubes of shaving cream, a bent and somewhat torn snapshot of a fat black-and-white cat asleep on a porch railing, three combs, two hairbrushes, a bottle of Wildroot hair ointment, a bottle of Fitch Dandruff Remover, a small, unlabelled box of glycerine suppositories, Vicks Nose Drops, Vicks VapoRub, six bars of castile soap, the stubs of three tickets to a 1946 musical comedy (“Call Me Mister”), a tube of depilatory cream, a box of Kleenex, two seashells, an assortment of used-looking emery boards, two jars of cleansing cream, three pairs of scissors, a nail file, an unclouded blue marble (known to marble shooters, at least in the twenties, as a “purey”), a cream for contracting enlarged pores, a pair of tweezers, the strapless chassis of a girl’s or woman’s gold wrist-watch, a box of bicarbonate of soda, a girl’s boarding-school class ring with a chipped onyx stone, a bottle of Stopette–and, inconceivably or no, quite a good deal more. Mrs. Glass briskly reached up and took down an object from the bottom shelf and dropped it, with a muffled, tinny bang, into the wastebasket. “I’m putting some of that new toothpaste they’re all raving about in here for you,” she announced, without turning around, and made good her word.

–Zooey, J.D. Salinger

It’s a bit like an Antonio Lopez Garcia scene, the passage from Salinger where Zooey is smoking in the tub behind a shower curtain and his mother is replenishing the bathroom’s stock of toothpaste. What’s always baffled me, with delight, about J.D. Salinger’s prose is how he can take a deadpan catalog of items in a 1950s medicine chest and bring it quietly to life, until it seems you are watching the cast of a Pixar movie where absolutely nothing happens. Nothing moves. Nothing breathes in there behind the mirror. In this case, nothing moves even when the lights go off. But every one of those little objects has somehow absorbed the life of the people who brought home those notions and creams and razors, concealing them behind the glass in which they see themselves every morning. In a less distinct way, the reader sees those characters too—Zooey and Franny and Bessie—even in this passage, glimpsing them in these simple things that share their life. It’s more than verisimilitude at work here. Somehow, in the way he offers this roster of humble, innocuous Glass family artifacts, though they would have been hardly different from the content of anyone’s medicine chest at the time, Salinger makes them luminous with a quality that’s impossible to name—they are little idiosyncratic treasures of fascinating intricacy, almost human in their individuality, though all of them were mass-produced. You feel as if you’re seeing them for the first time; as if you’ve never quite looked at a nail file before, even though he says nothing more than “a nail file.” They are nothing but what they are; stand for nothing beyond themselves. Yet they seem blessed by the author’s attention, somehow, marvelous because of their ordinariness. You see them the way you would if you’d been brought home after a last-minute pardon on the gallows and were thankful for every least thing in the world. But then everything in Salinger is like that.

That’s how a still life ought to work. It introduces you to the most mundane tokens of life in a way that doesn’t make them into anything they’re not. His prose somehow reveals how incredibly fine it is that they are so perfectly whatever it is they are. I think medicine chests are fast disappearing from this world, but I never open any of the remaining ones without seeing what’s inside with a heightened awareness of the world it embodies and how, in its own way, it shares my time on the earth. Sometimes, thanks to Salinger, what were formerly throwaway moments—applying a Band-Aid, say, or putting to use one of those other assorted less indigenous whatnots—become as worthy of attention and gratitude as anything else I might be doing.

This is all pretty darn close to the way Joshua Huyser’s watercolor portraits of everyday things work. Each time he posts a new painting on Instagram it’s a treat. He doesn’t mess with his subject. He reduces his picture to little more than the thing itself and nothing much else except maybe a shadow. His methods begin to seem like a sort of apophatic discipline, saying no to nearly everything but that quiet little yes in answer to the humble can or bowl or glass he meets gently with careful affection. He’s especially good with glass as if somehow the fact that it verges on total transparency, that it almost isn’t there—like his medium itself and the minimal means he employs—makes one of his paintings a lesson in the actual reality of things and people, all of us here, but oh so tenuously, and so easy to miss. Look at enough of his unspectacular still lifes, and you feel as if his subjects are only ostensibly inanimate objects. They are actually more like living companions on the daily journey, fellow travelers from 6 a.m. to curfew, friends to keep one company in the lonely sort of loving awareness that makes possible painting and a few other things maybe even more worthwhile involving actual, breathing people.

Comments are currently closed.