Happiness, courtesy James Neil Hollingsworth

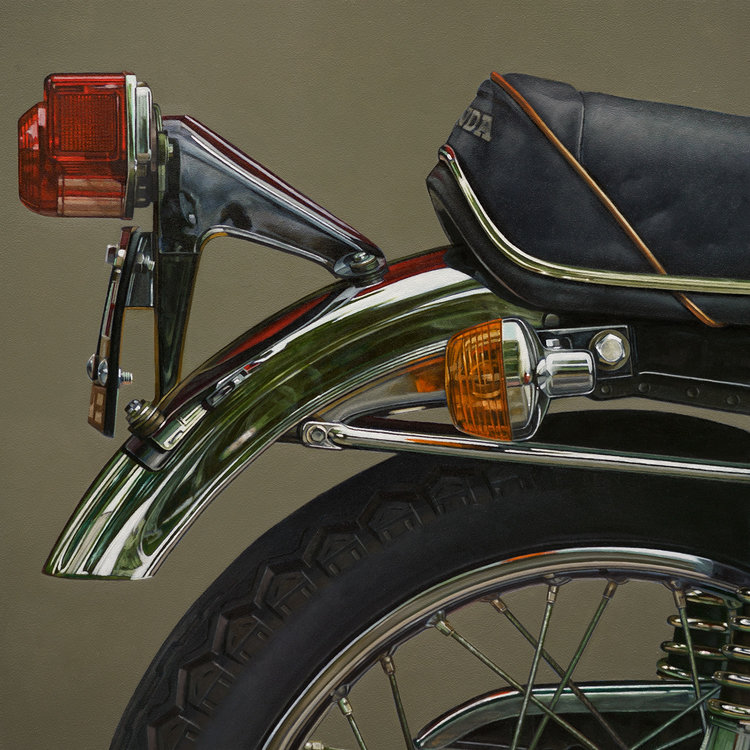

Honda: Aft, James Neil Hollingsworth, oil on panel, 12″ x 12″

To the prejudiced, everything that belongs to a certain category tends to look alike. Likewise, to its detractors, I suspect photorealism all looks the same. In their view, it smothers individuality. It’s impersonal and slick. It’s meretriciously seductive in its surface pleasures. And what makes it so galling: it’s popular. Although I use photorealist methods, I have been known to respond this way to some of the hyperrealism I see—opulently lavish with color and light and detail and yet seemingly devoid of subtle emotional tones. It’s so extreme in its technical skill that mostly it gives you an envious thrill similar to what you might experience while gazing at a Lamborghini on a showroom floor. I’d love to know how that car and those paintings are made, but I wouldn’t feel right bringing either of them home. I think that’s how many fellow painters react to this genre as a whole. It’s cool perfection seems as off-putting as a luxury item.

On the other hand, I could rattle off a list of photorealists whose work I love, as well as work that has the same deadpan, literal accuracy but relies to a lesser degree on photographic technology. (The Dresden painters, the French classicists, for example.) With his lenses and maybe mirrors, Vermeer would be the most beloved practitioner, of course, but many different contemporary painters working in this mode evoke far more than just a lust for looking. Their paintings find ways to convey almost exactly how things look, without any creative meddling, and yet also manage to be individually expressive by employing subtle, personal stylistic jigs—the self-limiting guides of an individual painter’s personal conventions and preferences. Some of these painters evoke a world of memory and stillness and poetry: the sense of order that saturates a certain kind of autumn afternoon, the smell and sound of a golf course, a childhood home in the dusk, or the look of a certain season in the way its light falls on things arrayed under a window. Behind all of that, throughout almost all examples of the genre itself, there’s an affirmation of the Apollonian order embedded in science and technology–its almost ontological presence in modern experience so omnipresent it becomes invisible, though it is what makes possible suburban homes and golf courses and lunches at a favorite diner and lavishly abundant supermarkets and quiet October afternoons scented with burning leaves when you can sit and do nothing in your backyard but listen to a remote motorcycle start up again at a green light. By and large, photorealism shows you how contemporary happiness looks and feels–you look at one of these paintings and realize how happy you actually are. Which is, by and large, what Vermeer wanted to depict as well.

I’m finding myself this year, in my own painting, concentrating on one sort of photorealist work that ought to have its own name: photorealist abstraction or abstract representation would describe it pretty well, though it deserves a shorter moniker I’m not clever enough to invent. Someone probably has already. In this type of work, the painter often takes a photograph of an isolated object or set of objects and then crops the image so that its abstract properties become paramount. The structure and color of what’s photographed become the armature for a painting that serves up a pattern of line, form, color and light, so that these qualities in and of themselves become the actual subject of the work—the style and the object or objects being painted fuse together so that the painting works as an accurate representation but also as an improvisation of color and line, simply by virtue of how the photograph was shot and cropped. I’ve been giving all of this a lot of thought because I’m working this year on enlarged images of small, colorful commonplace objects, yet—speaking of motorcycles—it’s the work of James Neil Hollingsworth that’s most on my mind. I first saw his paintings on Instagram, without ever happening to catch any of them at Arcadia on my visits to the gallery, except for my last one in January when I saw his small oil on panel of a classic Honda motorcycle’s tail light and rear turn signal along with portions of the bike’s wheel and seat.

His work at first looks like the sort of painting one might see at Plus One in London or one of several photorealist galleries in Manhattan, but the more you study his paintings the more you begin to see how his restrained use of color gives his work its own unique, quiet appeal. His almost minimal approach to color and composition is a good part of what makes his work stand out in comparison with hyper-realism that often seems dedicated to creating a highly saturated and extremely vivid rainbow of hues that appear to come straight out of the tube. One painting he’s done, of a salt and pepper shaker sitting behind a prone bottle of Heinz ketchup, could serve as an icon for the sort of abstraction representation I’m talking about. The painting uses objects so dear to Ralph Goings, in his wonderful glimpses of life in a diner, yet Hollingsworth arranges them to create a pattern of shapes and colors for their own sake, our of their usual context, simply for the formal properties they enable him to achieve in the painting. You don’t see beyond them through a diner’s window into a parking lot, but rather you see, with their help, a quasi-geometric composition of gray, blue/gray, red and white, green, and a thin strip of gold.

As much as they work as abstract formal compositions, his objects are illuminated by natural light, and he’s intent on using the actual color—without heightening it at all—of what he’s painting to invest the image with a kind of restrained joy. The rear fender of a classic Honda motorcycle gives him a template for juxtaposing the muted rose of the brake light against the butterscotch and honey tones of the turn signal, which are made even more piquant by the slash of varied greens in the chrome fender—which also reflects the rose and amber of the two lights. The taupe wall behind the bike, the other slight hint of red in the diagonal piping on the leather seat, the dark gray of the tire—all of these subtle colors click into place in what seems like geometrical inevitability. What this little painting has in common with most of his work is the way all of it is conveyed with understated elegance, with the freshness of first sight, but also how the reflections in the shining surfaces hint at some verdant scene behind the viewer, rather than beyond the object depicted, maybe a wooded expanse, with a twisty path waiting to be blazed on that bike. Even the wire wheels seem to reflect that same green prospect, a world opening away behind your head, portrayed with the slightest lines of color.

Many of his paintings seem bathed in this same Goldilocks light, not too bright, not too dark, with the background blanked out into a nearly uniform color, so that the lines and form of the object—a bowl of pool balls, a moped, a bicycle—rise up from the lower edge of the picture, like something breaching the ocean. His image of a moped intensifies this evocative quality of surfacing into view by being a study in aquamarine, everything shifting from teal to a wedge of slightly truer blue around three little ovals of deep red and amber in the scooter’s candy-colored rear signals. He balances all that negative space, the aqua sea of light, against the muscled tension of the scooter’s design, the mirrors like a crab’s tentacled eyes, everything suggesting sun, life, and freedom. This isn’t about speed; he doesn’t paint a Ducati. It’s just a moped, the preferred mode of transport for mods, not rockers. And only the top half of the vehicle at that. It bulges up into that blank field of blue like a twisted figure in a Francis Bacon. His esthetic is restrained, evocative, humble and yet beautiful as a gem. He paints ordinary joys with extraordinarily calibrated color. His particular color and light make the heart hum with remembered longings that began in childhood and only need paintings like this to remind you that they haven’t died but have only been ignored.

Many of his paintings seem bathed in this same Goldilocks light, not too bright, not too dark, with the background blanked out into a nearly uniform color, so that the lines and form of the object—a bowl of pool balls, a moped, a bicycle—rise up from the lower edge of the picture, like something breaching the ocean. His image of a moped intensifies this evocative quality of surfacing into view by being a study in aquamarine, everything shifting from teal to a wedge of slightly truer blue around three little ovals of deep red and amber in the scooter’s candy-colored rear signals. He balances all that negative space, the aqua sea of light, against the muscled tension of the scooter’s design, the mirrors like a crab’s tentacled eyes, everything suggesting sun, life, and freedom. This isn’t about speed; he doesn’t paint a Ducati. It’s just a moped, the preferred mode of transport for mods, not rockers. And only the top half of the vehicle at that. It bulges up into that blank field of blue like a twisted figure in a Francis Bacon. His esthetic is restrained, evocative, humble and yet beautiful as a gem. He paints ordinary joys with extraordinarily calibrated color. His particular color and light make the heart hum with remembered longings that began in childhood and only need paintings like this to remind you that they haven’t died but have only been ignored.

Comments are currently closed.