Windows onto the world

Selkie, collograph monoprint, Elizabeth King Durant

The current group show at Oxford Gallery, “Metamorphosis,” is one of the strongest James Hall has put together. Maybe because the theme signifies the essence of art itself. Art is alchemy, taking common human experience and transforming it into the idiosyncratic terms of an individual artist’s ornery insistence on his or her skewed way of seeing things. It’s a transformation of what could easily be a generic glimpse of something familiar into the odd, particular demands of one person’s heart. The greatest art goes a step further and somehow magically uses the unique weirdness of human individuality to open a window on the universal. A fleeting depiction of something partial and provisional offers a glimpse into what’s essential and enduring. Metaphor is metamorphosis. Yet, as Stephen Wright joked, “You can’t have everything. Where would you put it?” You can’t squeeze the whole world into a frame. But you can offer a door into it. In art, the part becomes the whole.

The best work in this show opens that door into the world as a whole. The pieces I keep going back to are the work from Debra Stewart, Elizabeth King Durant, Amy Mclaren, Barbara Fox, Phyllis Bryce Ely, Alexandra Latypova and, yes, even a few male artists, like Tom Insalaco and Daniel Mosner. (Has anyone else observed that the art women make right now often seems more vital and interesting than the work of their male cohort?)

Of all the work in Metamorphosis, my favorite has to be Durant’s Selkie, a perfectly executed and easily overlooked collograph monoprint visualizing the Celtic myth. Think Splash in more ancient terms, the shape-shifting of seal into woman and back again. There’s a perfect marriage of technique and subject in the print, with bravura, gestural lines seeming to articulate the shapes of seal and human in a sort of Taoist swirl of opposites. Her lines appear to be the edges of a three-dimensional surface, as if she had pulled the print from dried spackle applied with a knife—the wave that gives birth to both woman and seal also has the quality of a rock face, water transforming into stone. And yet another gentle polarity obtains in the tension between earth and heaven suggested in the extremely subtle shift between the emptiness of the grayish ultramarine sky above the slightly greener but almost metallic aqua of the sea under a mountain shoreline that quarantines those two regions. Her technique is spare and restrained and simple, yet the image looks timeless and primordial, an entire myth worthy of Joseph Campbell in a glance.

In a felicity that may be entirely unintentional, Alexandra Latypova’s misty landscape looks almost apocalyptic in the way she has suppressed the color of anything touched by the fog creeping toward the viewer from the horizon. The golden tones of what appears to be a foreground vineyard recede to a line where, at the edge of the fog and deeper into the haze, everything is sapped of hue. In Fog from The Bay, the ominous shapes of trees and shrubbery are faded to browns and grays, and somehow they seem to be in motion, becoming the fog that envelopes them, both collapsing and billowing up from the ground. The image reminds me of the live television feed from 911, the fall of the World Trade Center, where structures looming on the Manhattan skyline disappeared into dust. What may have started as a placid, idyllic morning on a lake’s shoreline has turned in a disquieting but eerily lovely reminder of the world’s end.

entirely unintentional, Alexandra Latypova’s misty landscape looks almost apocalyptic in the way she has suppressed the color of anything touched by the fog creeping toward the viewer from the horizon. The golden tones of what appears to be a foreground vineyard recede to a line where, at the edge of the fog and deeper into the haze, everything is sapped of hue. In Fog from The Bay, the ominous shapes of trees and shrubbery are faded to browns and grays, and somehow they seem to be in motion, becoming the fog that envelopes them, both collapsing and billowing up from the ground. The image reminds me of the live television feed from 911, the fall of the World Trade Center, where structures looming on the Manhattan skyline disappeared into dust. What may have started as a placid, idyllic morning on a lake’s shoreline has turned in a disquieting but eerily lovely reminder of the world’s end.

Amy Mclaren’s offering for this Oxford show, Retired, acrylic on canvas, upstages nearly all of her previous work in the gallery’s shows. Here she reminds me, surprisingly, of Norman Rockwell, his ease at suggesting deep emotional warmth through the depiction of facial expression and body language—in this case the stance and look in the eyes of an old dog. A  single greyhound, a retired racer, waits patiently at attention, wearing his worn racing color—it’s more of a visualized memory than an actual uniform here, dissolving into his flank. He poses against a nearly monotone but luminous blue background. The image has an iconic Pop simplicity, and the brushwork, as well as the way in which Mclaren positions the dog, boxing it in with the edges of the picture, flattening out the form, echoes Jim Dine’s robes. The very loosely applied globs of white to designate the greyhound’s paws are wonderfully accurate even though they almost look splattered onto the surface from the end of a brush fat with paint. The tension in the legs, the heartbreaking eagerness of the posture—please someone anyone give me another spin around the track—and the magnificently human look in that visible eye, the way it sadly studies whatever is happening in our faces as we loiter around this ex-champion indifferently, makes this image a wonderful, beautiful salute to all forms of guileless excellence and passion, especially when they have fewer and fewer chances to make their mark in the world. They also serve who only stand and wait . . .

single greyhound, a retired racer, waits patiently at attention, wearing his worn racing color—it’s more of a visualized memory than an actual uniform here, dissolving into his flank. He poses against a nearly monotone but luminous blue background. The image has an iconic Pop simplicity, and the brushwork, as well as the way in which Mclaren positions the dog, boxing it in with the edges of the picture, flattening out the form, echoes Jim Dine’s robes. The very loosely applied globs of white to designate the greyhound’s paws are wonderfully accurate even though they almost look splattered onto the surface from the end of a brush fat with paint. The tension in the legs, the heartbreaking eagerness of the posture—please someone anyone give me another spin around the track—and the magnificently human look in that visible eye, the way it sadly studies whatever is happening in our faces as we loiter around this ex-champion indifferently, makes this image a wonderful, beautiful salute to all forms of guileless excellence and passion, especially when they have fewer and fewer chances to make their mark in the world. They also serve who only stand and wait . . .

I had a similar response to Debra Stewart’s small, intricate oil on panel, Sea Change, with its title from Shakespeare that has  come to be almost the generic term for alchemy and metamorphosis. This lapidary dreamscape reminds me simultaneously of Botticelli and Disney, with a dash of Piero Di Cosimo’s strangeness. Like Mclaren’s greyhound, this little girl riding on the hips of a reclining mermaid strikes me as the most perfectly realized image out of all Stewart’s work I’ve seen. It uses symmetry to simplify a wealth of sedulously rendered detail: glistening highlights that appear to be laid on with gold leaf, but might simply be expertly handled oil. The way she presents the pink, vital face of the central girl in contrast to the murkier tones in the faces of her supernatural friends reminds me of the subtle distinctions in skin tone in Piero della Francesca’s Virgin Enthroned with Four Angels. The sense of depth, the way the bright ocean falls away behind the more shadowy figures, the transparency of the mermaid’s tail and the ghostly flying dolphins swimming through the girl’s arms, and the way the entire scene emanates from the figure of the central girl—Stewart’s self-portrait as a child?—give the image an undeniable quality of psychological truth despite its fantastic content.

come to be almost the generic term for alchemy and metamorphosis. This lapidary dreamscape reminds me simultaneously of Botticelli and Disney, with a dash of Piero Di Cosimo’s strangeness. Like Mclaren’s greyhound, this little girl riding on the hips of a reclining mermaid strikes me as the most perfectly realized image out of all Stewart’s work I’ve seen. It uses symmetry to simplify a wealth of sedulously rendered detail: glistening highlights that appear to be laid on with gold leaf, but might simply be expertly handled oil. The way she presents the pink, vital face of the central girl in contrast to the murkier tones in the faces of her supernatural friends reminds me of the subtle distinctions in skin tone in Piero della Francesca’s Virgin Enthroned with Four Angels. The sense of depth, the way the bright ocean falls away behind the more shadowy figures, the transparency of the mermaid’s tail and the ghostly flying dolphins swimming through the girl’s arms, and the way the entire scene emanates from the figure of the central girl—Stewart’s self-portrait as a child?—give the image an undeniable quality of psychological truth despite its fantastic content.

Barbara Fox, as with many of her fellow exhibitors, contributed one of her most realized pieces, a composition as simple and iconic as a Gottlieb burst painting. Entitled Fly Me to the Moon, it offers a leaf of sheet music, folded like origami, under a full moon. The theme is the polarity, and unity, of art and the world it represents—a song about a moon launch inscribed on an earthbound sheet of paper folded into a bird-like form. It both can and can’t transport you to that destination only inches away in the charcoal and pastel drawing, suggesting bittersweet ironies held in perfect balance. Look again and the folded sheet music could be an opening hand tossing the moon into the sky.

iconic as a Gottlieb burst painting. Entitled Fly Me to the Moon, it offers a leaf of sheet music, folded like origami, under a full moon. The theme is the polarity, and unity, of art and the world it represents—a song about a moon launch inscribed on an earthbound sheet of paper folded into a bird-like form. It both can and can’t transport you to that destination only inches away in the charcoal and pastel drawing, suggesting bittersweet ironies held in perfect balance. Look again and the folded sheet music could be an opening hand tossing the moon into the sky.

In Becoming Ice, what seems to be another painting inspired by photographs her father took of the Arctic, Phyllis Bryce Ely keeps finding fascinating ways to turn so much whiteness into beguiling imagery. Here it seems  frozen flotsam, breaking away from icebergs, swirls around itself in the ocean forming what looks almost like a huge lens, an eye of water, gazing up at the cold heavens. At first, the viewer takes pleasure in the sensuous quality of the paint, the way it has been so loosely and vigorously applied with confident gestures. The sky is chunky, a chock-a-block assembly of warm and cool lights and darks, with her bright orange undercoat peeking through here and there—in a way that looks both unnatural and yet real. Yet for all that rocky solidity in the clouds, it all looks like a brilliant sample of the sky from Western New York, over Lake Ontario or one of the Finger Lakes. The way the surface of the water works in this painting is equally mystifying: it looks shiny and reflective without any symmetry between the shapes in its surface and the clouds above. It almost seems a visualization of Emerson’s most awkward metaphor, the transparent eyeball, signifying the unity of subject and object, observer and observed.

frozen flotsam, breaking away from icebergs, swirls around itself in the ocean forming what looks almost like a huge lens, an eye of water, gazing up at the cold heavens. At first, the viewer takes pleasure in the sensuous quality of the paint, the way it has been so loosely and vigorously applied with confident gestures. The sky is chunky, a chock-a-block assembly of warm and cool lights and darks, with her bright orange undercoat peeking through here and there—in a way that looks both unnatural and yet real. Yet for all that rocky solidity in the clouds, it all looks like a brilliant sample of the sky from Western New York, over Lake Ontario or one of the Finger Lakes. The way the surface of the water works in this painting is equally mystifying: it looks shiny and reflective without any symmetry between the shapes in its surface and the clouds above. It almost seems a visualization of Emerson’s most awkward metaphor, the transparent eyeball, signifying the unity of subject and object, observer and observed.

The rest of the work in this show is just as interesting: Tom Insalaco’s magisterial, Baroque depiction of time and eternity, Daniel Mosner’s sumptuously rendered, alien-looking vegetables sitting on an abstract table in an expanse of negative  space, and Helen Santelli’s two ceramic paeans to the magic of insect metaphorphosis—a recurring theme in the work of several artists. What I especially liked was the inclusion of a cicada in Santelli’s constructions—an insect that was almost a talisman of my childhood, an enduring emblem for me of spiritual freedom emerging from the confinements of life. There are instances of wry humor in the show—cheerful laughter being a quality in short supply throughout much of the art world—in Doug Whitfield’s middle-aged, slightly gone-to-seed Superman revealing his inner superhero without a phone booth to conceal his metamorphosis in the age of smartphones. Bill Santelli’s Mindstream #3, a prismacolor drawing quite different from his usual swaying stalks of field grass. Striking and bold, it looks deceptively like a lithograph. Jean Stephens, again with a touch of humor, depicts one of her southwestern monoliths or wind-carved dolmens, with an enormous paper bag, bringing out the visual kinship between brown paper and sandstone, large and small, natural and human. Ryan Schroeder continues down the path he appears to be on, limiting his pallet to depict fields of light, condensing into objects, focusing on how to convey a kind of timeless illumination in a carefully rendered, but entirely blurred interior full of poetry, seemingly a memory from half a century ago, before he was born. Amy

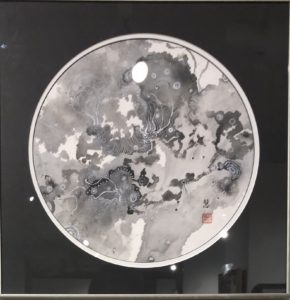

space, and Helen Santelli’s two ceramic paeans to the magic of insect metaphorphosis—a recurring theme in the work of several artists. What I especially liked was the inclusion of a cicada in Santelli’s constructions—an insect that was almost a talisman of my childhood, an enduring emblem for me of spiritual freedom emerging from the confinements of life. There are instances of wry humor in the show—cheerful laughter being a quality in short supply throughout much of the art world—in Doug Whitfield’s middle-aged, slightly gone-to-seed Superman revealing his inner superhero without a phone booth to conceal his metamorphosis in the age of smartphones. Bill Santelli’s Mindstream #3, a prismacolor drawing quite different from his usual swaying stalks of field grass. Striking and bold, it looks deceptively like a lithograph. Jean Stephens, again with a touch of humor, depicts one of her southwestern monoliths or wind-carved dolmens, with an enormous paper bag, bringing out the visual kinship between brown paper and sandstone, large and small, natural and human. Ryan Schroeder continues down the path he appears to be on, limiting his pallet to depict fields of light, condensing into objects, focusing on how to convey a kind of timeless illumination in a carefully rendered, but entirely blurred interior full of poetry, seemingly a memory from half a century ago, before he was born. Amy  Chen’s work, just inside the gallery’s entry, is marvelous—a study in deliquescent, meandering washes of ink and watercolor on rice paper, working with traditional Asian materials and media and yet letting the round image evolve into something almost entirely abstract and ethereal, reminding me of how Bill Santelli works with acrylic in his other modes. Chris Baker offers a beautiful single-object still life, if you don’t count the objects almost lost in the shadows behind the simple glass jar with flowers. And with Bunker, Jacquie Germanow depicts an almost cinematic and unearthly scene that held my attention as long as any other painting on view. A shaft of light connects sky and sea, like those alien beams for transporting people in the X Files, if it’s actually the Earth and one of its oceans we’re viewing rather than a landscape from a lost Dante canto. Water seems to flow down over a long tunnel, a bunker, that glows like a furnace and has a barred entrance adorned with a ram’s horns. It’s all ominous and beautiful in a way that makes it impossible to pin down why all of this beckons to you, but it is mysteriously, disturbingly inviting.

Chen’s work, just inside the gallery’s entry, is marvelous—a study in deliquescent, meandering washes of ink and watercolor on rice paper, working with traditional Asian materials and media and yet letting the round image evolve into something almost entirely abstract and ethereal, reminding me of how Bill Santelli works with acrylic in his other modes. Chris Baker offers a beautiful single-object still life, if you don’t count the objects almost lost in the shadows behind the simple glass jar with flowers. And with Bunker, Jacquie Germanow depicts an almost cinematic and unearthly scene that held my attention as long as any other painting on view. A shaft of light connects sky and sea, like those alien beams for transporting people in the X Files, if it’s actually the Earth and one of its oceans we’re viewing rather than a landscape from a lost Dante canto. Water seems to flow down over a long tunnel, a bunker, that glows like a furnace and has a barred entrance adorned with a ram’s horns. It’s all ominous and beautiful in a way that makes it impossible to pin down why all of this beckons to you, but it is mysteriously, disturbingly inviting.

Thank You, Dave, for your kind words and observations!