H.K. Freeman’s husbandry of her medium

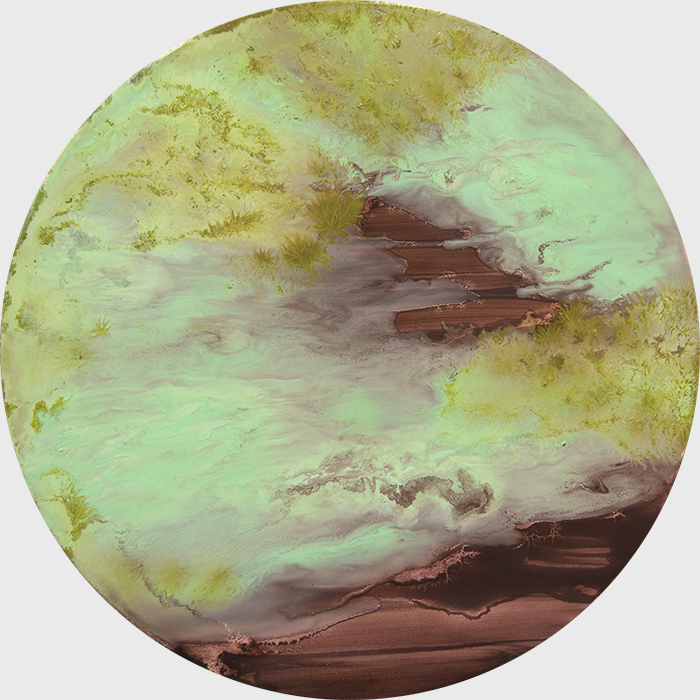

Moment #34, H.K. Freeman, oil on panel, 18″ diameter

I collect spoors, molds and fugus.

In the fungus among us, H.K. Freeman sees a world suffused with seemingly chaotic but purposeful mystery. That alone marks her as someone worthy of attention. Fascination with things almost everyone else ignores or shuns, for me, is a springboard for originality in visual art. She is yet another interesting artist I discovered in Manifest’s recent Painted exhibit. Freeman’s current obsession reminds me of Emmett Gowin’s full immersion in the South American rain forest, devoting himself to capturing moths, not with a net but with his photographic lens. Yet moths are already beautiful. Anyone who has come across a cecropia moth, as I once did in our back yard many years ago when we lived in Utica, will not be able to look away, the wings are so Blakean in their eerie glamour. With fungus, not so much. Noting the mold on my basement cinder blocks after a rainy month, I reach for the bleach.

But Freeman is a spiritual cosmologist. She sees wonder and mystery in what others recognize only as decay. She marvels at a devouring life form that is neither animal nor vegetable, but something that eats the world’s leftovers as an after-after-party clean-up crew. In all fairness, anyone who has enjoyed a portobello or truffle knows that fungus can taste pretty good, as well. Freeman shows us something more rarefied in her sometimes tiny spherical paintings of fungus that look like miniature worlds viewed through a microscope, or the surface of planets light years away.

But Freeman is a spiritual cosmologist. She sees wonder and mystery in what others recognize only as decay. She marvels at a devouring life form that is neither animal nor vegetable, but something that eats the world’s leftovers as an after-after-party clean-up crew. In all fairness, anyone who has enjoyed a portobello or truffle knows that fungus can taste pretty good, as well. Freeman shows us something more rarefied in her sometimes tiny spherical paintings of fungus that look like miniature worlds viewed through a microscope, or the surface of planets light years away.

She’s at her best when she finds a symbiotic strength in her medium’s proclivities, offering a little guidance here and there—like a color field painter pouring and steering a flow of paint. It’s both a practical and a symbolic relationship with materials. Anyone who has worked in the natural world, say, growing a garden, recognizes the partnership. The garden does most of the work. Anyone who has tried to steer himself or herself through the world recognizes how free will represents a tiny marginal allowance you earn through prior discipline, simply for the chance to choose against the daily inertia of one’s character. You are there to nudge things—including yourself—this way and that, toward the desired end. When she finds the effects she wants by letting the paint do what it does on its own, but  intervening where needed, the work is enchanting.

intervening where needed, the work is enchanting.

What’s marvelous is that, in this fascination with one of the lowliest of life forms, she sees God. She doesn’t preach, just passes along her awe at how much order and beauty and shines forth from the world of decomposition. She’s working a field Richard Wilbur tilled in his great poem about the vulture, and how that carrion bird’s meals serve the same purpose as an ark, delivering life from death.

From Freeman’s website:

The intricate worlds of lichens, fungi, and mosses serve as a starting point for my paintings. These sublime organisms help ensure and maintain life on earth. I draw upon the history of landscape painting and abstraction, together with eco-theology, to communicate spiritual ideas in relation to creation. Using the finite to think about the infinite, the paintings evoke the mysterious, wondrous, interconnected process of existence.

I alternately manipulate the paint and playfully relinquish control to create these worlds. The imagery simultaneously fuses and dissolves, oscillating between certainty and uncertainty with the promise of resolving into something familiar. The luminosity of the colors and the use of abstraction convey the euphoric, transcendental sensation of my initial encounter with the subject matter. The abstraction and the colors stimulate not only the visual senses, but also act on the psyche to contemplate the painted microcosms. I hope the references to creation will invite viewers in, while the abstraction will challenge viewers to perceive in a way that goes beyond the surface of the painting, so they can explore their own thoughts and beliefs.

Comments are currently closed.