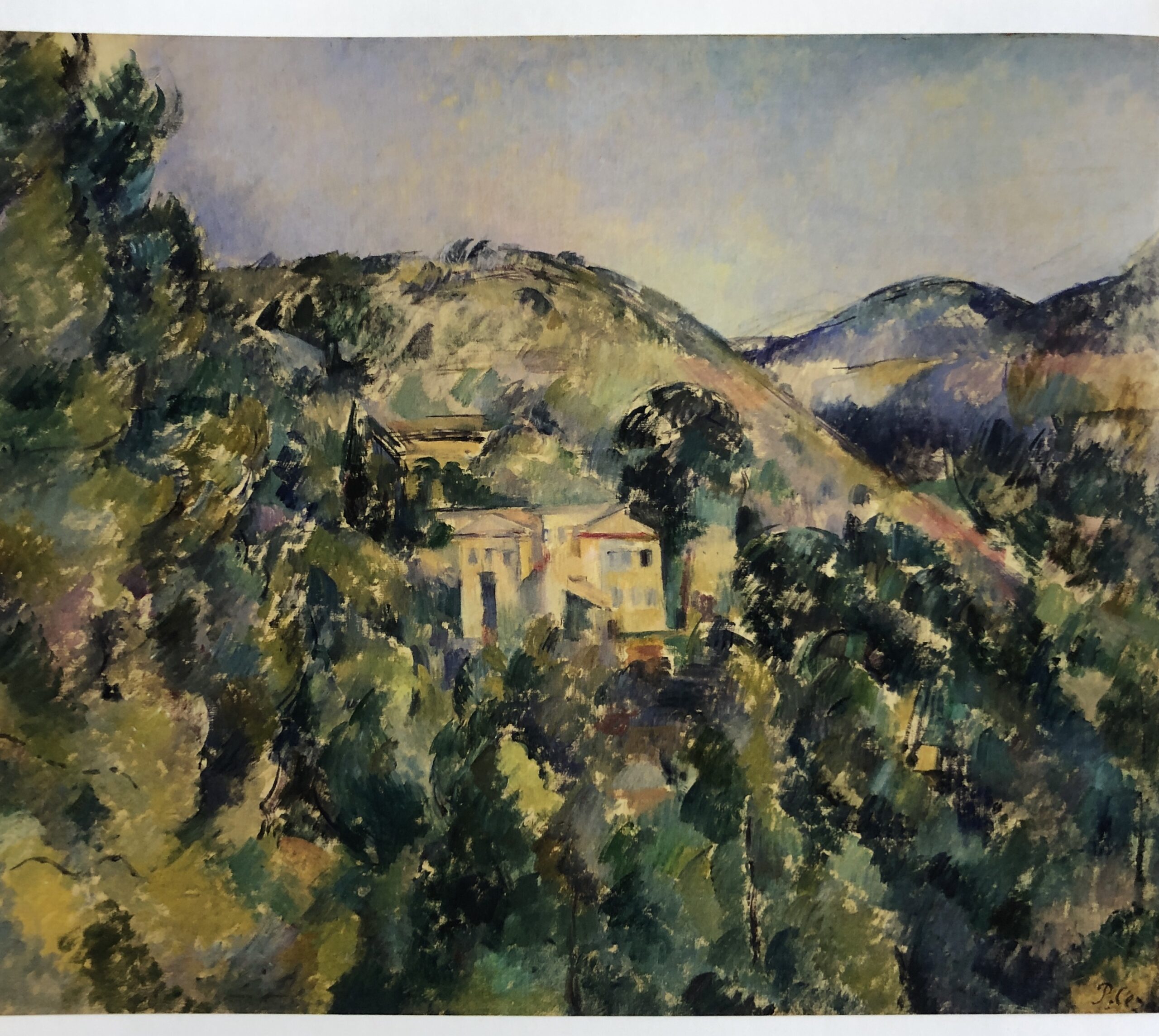

The hermit of Aix’s color

View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph, Metropolitan Museum of Art

I saw this painting almost exactly ten years ago at Cezanne and American Modernism at the Montclair Art Museum. After all these intervening years, I finally bought the catalog for the show. It’s a hardbound book once in the collection of the Art Institute of Pittsburgh Library, with the little envelope for the library loan card still glued just inside the cover. Purchased through a third party on Amazon, the book was finally a bargain. I bought it because seeing this show revealed so much about Cezanne’s influence on American painters and because this particular painting had such an impact on me when I was at the museum. I wanted to see the work in the show again after all this time.

The almost iridescent quality of the variations in color from the hillsides down into the forest, the way in which each mark hummed vibrantly in harmony with every other mark in that field of paint, left me more in awe of Cezanne’s color than ever before. I’m struck more and more by how Cezanne’s greatness has, for me, so little to do with his enormous historical influence. It’s ironic to react that way to a show designed to confirm his enormous affect on later American painters. But it seems that his influence had less do with with his theories–in other words his position in history–and seems so much more a result of the unique, lyrical feeling his paint inspires. His color, his handling of oil is almost always understated, and he seems to always find combinations of tone that make time itself visible–as Vermeer does in a different way. It derives from the intensity of his subdued passion for what he sees as he translates it into paint, which is hard to square, so to speak, with his famous dictum about interpreting nature geometrically, the advice that gave birth to Cubism. I wonder if his stress on seeing nature as sphere, cone and cylinder was merely an arbitrary way of imposing self-restraint to temper his passion for the colors of oil paint. He forced himself to think about form and volume rather than color and as a result his color became more subtle and unique. His actual achievement could have been almost as an incidental byproduct of the geometrical guidelines uppermost in his mind–even though color was what drove him to paint. Somehow, in the lower left hand corner, I see Gorky, of all people and I don’t mean the early paintings Gorky did which are hugely talented imitations of Cezanne. I mean his later paintings and his self portrait with his mother–the line and shapes and even a bit of the color. Cezanne is a marvel–and one can see why he could be classified as both an Impressionist and Post-Impressionist, though he was unlike everyone else in any category. He was perfectly himself.

Comments are currently closed.