Han’s solo

Decades ago, my wife and I (with our infant daughter) moved from my first job in Great Falls, Montana to Utica, New York. Within a year or two of that move, I attended two seminal exhibitions at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, where I was enrolled in art instruction for a time. I had consciously refused to attend art school, even though I’d started painting seriously in my mid-teens, and made up for it by working with artists at places like MWP and later at Memorial Art Gallery. I’m going to write elsewhere about the article in Art News that turned me against the world of art in my teens–it’s intellectual pretensions, the post-modern obscurantism of art criticism, the way in which so much art during and after the Sixties arose out of a kind of snotty disdain for the ordinary life of common people. It was all repellent to me, and the artists I loved like brothers at the time–Blake, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, Braque, Rouault, Klee–struck me as obsolete, historically relevant but offering nothing for a contemporary artist to assimilate. I was too put off by the comparative austerity of Diebenkorn’s abstractions to see how they sprang almost directly from Matisse. But even aside from the way in which the art world seemed like an exclusive club devoted to making itself inaccessible to most people, I believed that I was a late-comer who had no place in the world of contemporary art. I looked at the increasingly sterile ways in which The Next Big Thing in art simply confirmed how all the revolutions were over and there was nowhere new for painting to go, if you understood progress as increasing levels of freedom for visual artists. I didn’t see what was actually going on, the way Arthur Danto did–how Pop Art made anything possible and therefore anything was now acceptable and contemporary. Anything could be art, including the sort of work done in the past. So I continued to paint, out of my own sense of inner necessity—but feeling as if my work had no place in the larger scheme of things, rather than paint and teach, I became a reporter and a writer.

Yet when I found myself walking into “An Appreciation of Realism” at Munson-Williams-Proctor in the 80s, I realized what was still possible, and how I’d missed the way art had become, in a sense, ahistorical. It was an exhibition devoted to representational painting and the roster of artists represented was incredible: Bailey, Estes, Pearlstein, Beal, Kahn, Lennart Anderson, Freilicher, Soyer, Leslie, Resika, Jerome Witkins, Katz, Welliver, Guston, Goings, Cottingham, Close, Bechtle, Fish, Beckman, Paul Georges, Leland Bell, Rackstraw Downes, and Fairfield Porter, along with more than a dozen others. It was an amazingly comprehensive curation of contemporary representational painting by all the names that I continued to study for years after I saw that show. It opened my mind to the possibility that I might actually be able to paint in ways that would belong to what was happening in art around me. It showed me, essentially, that it was possible to be any sort of painter I wanted to be–and all that remained was to spend years figuring out exactly what that was, which I did, slowly and patiently.

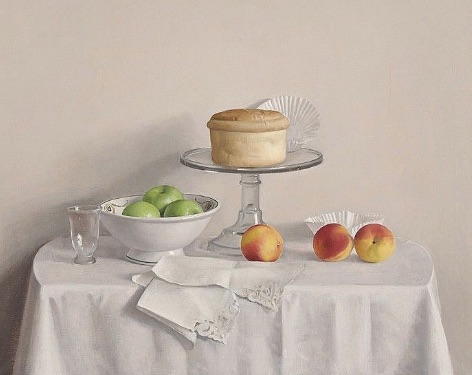

What’s interesting to me now is that photo-realism was well-represented but didn’t move me, and that I don’t even recall the work by Fairfield Porter, someone whose paintings I love as much as anyone who has ever picked up a brush. In short order, the arts institute organized a second show which had an even more profound effect on me: a large solo exhibition of Raymond Han’s still lifes. He was born in Hawaii in 1931 and died three years ago in upstate New York. He never got an art degree, but learned from other painters—as I did—and attended the Art Students League. His large still life work in the early 80s was astonishingly masterful: large tables covered in white tablecloths, where he had carefully arranged china, glass, silverware, all of it in tones of white, gray and brown, with small areas of intense color provided by a bit of fruit or flowers. His tables were set back against an off-white wall, his objects casting faint shadows against the wall, all of it like a little domestic city spread out on the fabric, a planned community where each object had been placed with infinite care. He had no desire to paint what he saw in his environment, just as he found it, but created the painting by placing everything where it needed to be to yield a certain kind of balance and serenity—in the way William Bailey does, but with an entirely different feel for his earth tones and matte surfaces from a level, frontal perspective. Han allowed you to look slightly down from in front and above the tabletop. The effect was to give you a glimpse of a snowy landscape, mostly variations of white, with objects and spots of beautiful color all the more powerful for being so rare.

So few of the paintings I saw in Han’s solo exhibition can be found anywhere on the Internet now. Most of what I find is work from more recent decades, almost nothing dating from the 70s or 80s. They were large canvases, four or five feet across, which enabled him to paint a tureen or compote in its actual dimensions—something I have attempted to do in my own still lifes ever since. His white tablecloths translated into the ones I used for my large tabletops, which were a sort of compromise for me between my desire to assimilate much of what I discovered in Han’s work with my love for Braque’s gueridons (his tabletops tilted forward to a plane almost parallel with the painted surface).

Han’s tables remind me a bit of Buddhist altars: a place for devotional vessels and perishable offerings to the Buddha or a bodhisattva: flowers, fruit, or incense. The formality and elegance of that white linen where he places household objects, like the pale sand a Zen gardener punctuates with a rock or plant, suggest both abundance and restraint, a relaxed order so different from similar displays of costly crystal or lace napkins in a dark Upper West Side dining room painted by John Koch. There’s a humble, unpretentious air in the way Han placed a fluted paper coffee filter with as much care as a bit of expensive fabric—because he wanted a slightly different tone, a variation of his ubiquitous white, the soil from which would spring the warm tones of a peach or a peony. The ratio of white to lovingly rendered color represents a sort of standard in the back of my mind against which I often measure my own handling of color. Han had a gift for being able to put a white tablecloth against a white wall and then assemble a dozen white dishes and bowls on that surface—and still handle the subtle variations in value required to render a highlight on a spoon or a shadow in a bit of drapery in an absolutely convincing way—without (and this is what gives life to his work for me) relying on arduous hyper-realism. With realists like Koch or James Valerio or William Beckman, the ability to achieve startling verisimilitude depends on a certain tolerance for darkness. The delicacy of color sometimes in Koch represents a sort of triumph over that darkness that Valerio’s lighting and more saturated colors don’t achieve, even though Koch’s interior scenes tend to be dark. In Han, shadow is almost banished, relegated to the corner folds of his tablecloths or a penumbral wedge on the wall behind a table. The natural light that illuminates everything in one of those big still lifes has stayed with me for decades, the sort of light that strikes the eye from even the darker quarters of a Fairfield Porter canvas. My candy jars were my attempt to paint an image that has depth and realistic form without relying on dark values at all, so that even less illuminated nooks between one jelly bean and the next glows with a certain kind of light. Han’s big tables have that quality: the light seems to reach every surface, the background almost as bright as the foreground. And when you get close to one of Han’s canvases, you know it’s a painted surface, with evidence of his brush. At the time, the little take-away card printed up for the show compared his work to Chardin’s, and though the feel of his work doesn’t resonate with the still life Chardin did before he immersed himself in genre painting, when Chardin returned to still life, the feel of a painting like Wild Duck with Olive Jar does find echoes in Han’s best work.

Comments are currently closed.