Monastic. Cheap. Admirable.

Does anyone still remember those skits on Conan from more than two decades ago where President Clinton would appear as a digital mask worn by Robert Smigel? The writer did a ludicrous, but hilarious, impersonation of Bubba as a Southern party boy living it up and getting away with everything and anything. “I gotsta gotsta have my snacks,” he crowed. And he was talking as much about Monica Lewinski as a side of French fries. A still shot of Clinton’s face on the monitor was lowered into the guest position beside Conan’s desk and within that motionless and grinning face, Smigel’s real-time mouth displaced Clinton’s lips—the writer’s mouth speaking his lines while the President’s face was still frozen into that vote-getting, Teflon grin. It was very funny and outrageous, and it would probably be impossible to perform these days, given much of what was being said, for many reasons. It was so over-the-top and explicit that it took on a reality all its own. (Come to think of it, that would be a good way to describe much of the art world over the last century.)

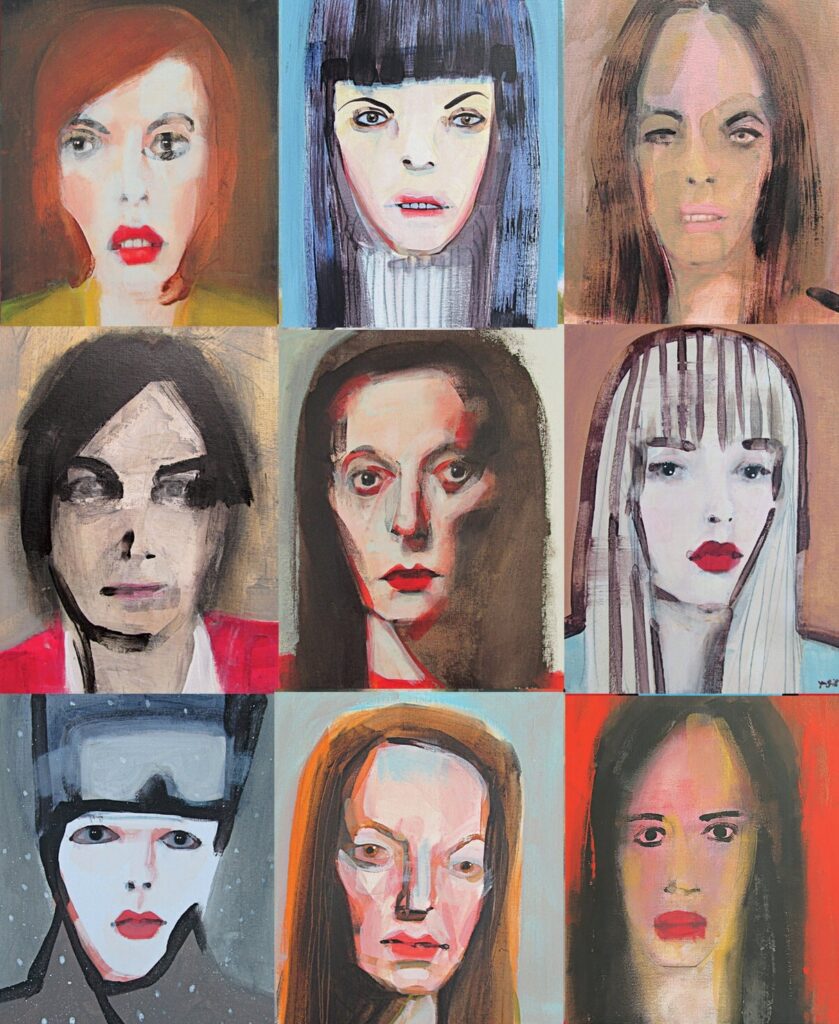

Those Smigel skits were the first thing that struck me when I saw these $100 portraits of women at The New York Times. The eyes in some of them look as if it were somehow possible to have Photoshopped them into the paintings, like Smigel’s good-old-boy accent. Could the paintings have been done on top of the photographs used as a support? Regardless, they’re good. I loved those boundary-testing skits on Conan, because they simply pointed out that when someone is doing what you want him to do, he can get away with nearly everything else in his life. Again, like the rules that once obtained in the art world. (Rewatching the first season of The Wire this week confirmed that lesson as well in terms of Baltimore politics and law enforcement as observed by David Simon.) In my view, the ends are never enough to justify the means, and integrity matters, but I may be in the minority these days.

In these one painting-per-day style portraits, Jean Smith conveys a subject’s eyes with an eerie photographic precision about how the cornea and iris reflect light, but the eyes are framed by a gesturally primitive mask. These souls are looking out at you from behind their own almost graffiti faces. A few of them I wish I’d bought: I mean, why not, for $100? But I like them. Yet her point is to undermine the economy that continues to push the ownership of visual art into an elite economic ghetto of the uber wealthy.

I shouldn’t be talking this way. The work I’m doing now takes weeks without it’s done without interruptions, usually a minimum of four weeks per painting, but also as long as two months with the sort of interruptions that you face when you actually have a life outside the studio, as I still do. No one can afford to put in four to six to eight weeks on a painting that sells for $100. But the point Nick Marino makes in his piece for the Times is that artists aren’t even reaping the actual profits of what has become an extension of the stock market—paintings are now purchased for high prices at the start and then their value is repeatedly inflated through resale or auction, simply as some corollary to day trading Silicon Valley stocks or investing in Bitcoin. (This can’t last. Our financially leveraged economic boom will not continue forever. The art world bubble will burst along with the others, but it may go on for quite a while.)

I love the idea of doing paintings quickly and selling them for unusually low prices. Jim Mott and Harry Stooshinoff are making wonderful, even remarkable paintings in this mode, along with many others. These quick portraits of women offer a continuous experimentation in ways of seeing and representing nothing more than how light lands on an individual face and how the eyes look out from the prison that personhood can seem—when in fact human individuality is the greatest miracle of life.

Excerpts from Marino’s piece:

I can appreciate that beauty has monetary value, particularly for the one and only example of a particular exquisiteness. Someone spent time making it, and that person should be compensated. But even modest artworks can be out of reach for almost anyone who’s not a real estate mogul, shipping magnate, stockbroker or oil baron. Under the sanctimonious cover of “arts patronage,” these plutocrats use art to launder their money, trading up the value of young artists and enriching one another in the process. The artists, meanwhile, get paid only once, on the initial sale. The end result is (artwork) that costs as much as a Honda Civic.

Opting not to use a gallery, Smith listed each of her works on Facebook for the ludicrously low price of $100. She could certainly charge more, but the egalitarian price is the point. It’s her version of the $5 tickets Fugazi used to sell to its all-ages shows — and anyway, she has never needed much to survive. For the past quarter-century, she has lived alone and monastically in an apartment without a sofa or kitchen table (she eats off a filing cabinet), and her monthly expenses, including rent and utilities, total about $1,000. She only needs to sell 10 pieces per month to break even — though that has never been her problem.

Well, that’s all she needs to make if she doesn’t pay taxes. But at that level of income, she wouldn’t need to pay taxes. He points out that having created an insatiable demand for her low-budget art, she can’t keep up with it. The question is, does she keep her prices low or do what the free market naturally does when demand far exceeds supply: let prices rise as far as demand will lift them. I’m guessing it will depend on whether she ever gets a mortgage. I hope she continues to live monastically, as Marino describes her lifestyle. Monastic is almost always unimpeachable as a way to live, especially for an artist. Thoreau, or “Pond Scum” as The New Yorker referred to him once (at the link, you’ll see a note at the bottom of the essay pointing out the original headline), proved that monastic individuality isn’t such a bad way to live until people come in the winter and start cutting up your pond and selling it as blocks of ice.

The other takeaway here: hey, Facebook is still good for something.

Comments are currently closed.