BLM vs. MLK, spiritual art, apple fritters

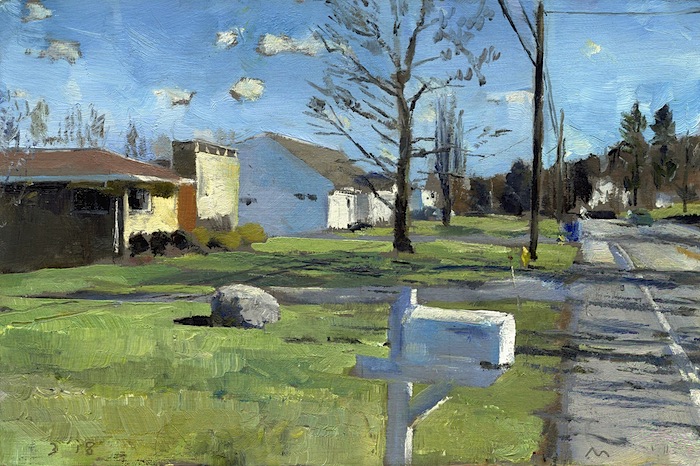

Jim Mott’s painting of a mailbox, after arriving at this spot in his Landscape Lottery.

Jim Mott came by this weekend for a conversation after a long absence, and we picked up more or less where we’d left off last time, talking partly about spirituality, art and God, BLM vs. MLK, his new art project, and some other things I ordinarily don’t talk about, like apple fritters. Though Jim is deeply political, in a way that goes back more to the Sixties than what’s happening now, he’s the least confrontational and least angry political person I know. Many people obsessed with politics seem to have embraced it as a substitute for religion. Jim already has a faith, so politics is simply a way of thinking about how to put that faith into action. What I like about his politics and his religion are the way in which they get submerged into his paint, in a sub-rosa way, neither overt nor strident, producing work that embodies his spirituality rather than illustrates it, if that makes sense. Most of the artists I’m close to are deeply spiritual, but each one in a very different way from the others. Here’s a good portion of our long conversation:

Dave: I went through this spiritual crisis in my teens and it was discovering Van Gogh who got me into it.

Jim: The crisis?

No, he got me into painting. He was so screwed up, but he responded to it by painting. He started by preaching and then went from that to painting, so it was kind of the way he dealt with there being something wrong with the world, or with him.

There’s that romantic notion or tradition that the world doesn’t get it and the individual poet does, so you’re at odds with the world.

It was just the opposite of that with me. I didn’t get it. Life was absurd and I didn’t get it, but that was repugnant to me, so at some level I knew I wasn’t right to have that perception. That was my dilemma. The idea that meaning seemed impossible and this was a crisis, a problem. It seemed the world was pointless and amounted to nothing, and this was horrifying because I couldn’t see out of that mental trap. But there’s a contradiction I didn’t see in this. Camus based The Rebel on a recognition of this contradiction: that people inwardly rebel against nihilism. If nothing matters, then there’s no reason to be dissatisfied with that, just enjoy what you can and that’s that. Why is it horrifying that life seems to amount to nothing? There’s some context in which the absurdity of life is unacceptable but if everything is genuinely pointless how can anything be unacceptable? I couldn’t get to that state of “there’s no way any of any of this can really matter, including my anguish over the impossibility of meaning, so I might as well enjoy life while it lasts.” I couldn’t reconcile myself to this nihilistic certainty I had. So I looked at Van Gogh because I assumed he had to have gone through something like that and responded to it by painting. I’d already been painting pictures of my favorite guitarists, Hendrix, Clapton, Bloomfield. I was in a band, I loved playing my Telecaster. I did the paintings just to have them on my walls. Enlarged copies of album covers. Then I read about Van Gogh and thought, hm, painting is an activity that’s interesting in itself, partly because Van Gogh, this incredibly discontented guy, was so devoted to it. Van Gogh got me to that point. My reading later gave me a way to understand this crisis I’d gone through in a spiritual perspective. So the painting and the spiritual perspective merged.

When you’re doing a good painting you feel like you’re participating in something larger than yourself, at some level it’s about ego-lessness and service. Given all that, the way the art world is all about ego competition and material symbols of success, what would happen if, I don’t know, what happens to you when you buy into that at all. You’re doing what you need to do to advance yourself but, as a result of that, cutting yourself off from your deepest, most authentic sense of what it’s all about – and that awareness of doing something in service to something larger, that awareness and how it imprints itself on the painting, that might be as important to the viewer as all the other qualities that would make a painting conventionally successful.

You mean given the art world’s definition of success. Should you fight it or resist it? That’s always a question.

You’re working to show this . . .

Mystery . .

Right. The art world wants someone who’s world-famous. If someone had handed me world fame, I’m not sure I’d turn it down, but . . .

If it does amount to something, a painting, then if you aren’t known, how do you get it out there? Something essential to your life, how do you connect it to other people?

Even with the significant but moderately narrow level of recognition we get, is it worthwhile to generate a counter-narrative about what it’s all about? As an alternative to the pursuit of the material rewards or even critical recognition. I don’t know. Just to have a small audience to tell that to, you’re still having an impact. Integration is the mission now for me: art and spirit, left and right.

<Behind him on the little end table, I always display his night painting of the Memorial Art Gallery and nearby Tom Insalaco’s painting of an eclair. We have a sidebar discussion of eclairs vs. apple fritters and where to find the best fritters, which was possibly the most impactful part of the entire conversation, but not worth transcribing.)

So what are you painting?

Well, I find I’m not very motivated unless I have a project. So I’m doing this project with my wife’s niece. During the protests, my wife was saying the protestors were destroying the neighborhood where she’d grown up here in Rochester. She said, “My friends in the suburbs were cheering them on, but the people who live there, the ones the protests are supposedly helping, don’t have anywhere to get groceries now. She said, “Defund the police? What are the victims of domestic violence going to do when they’re getting beaten? So she was thinking of writing an essay. She knows the inner city. Her family comes in all colors. She’s keenly aware of racism and poverty. She was writing an essay about how your lawn sign isn’t helping anyone. She had just visited her niece. Her niece’s son, whose father is Black, doesn’t see those signs. What he does see is poverty and chaos and a school system that’s failing. He’s in third-grade at a school where the majority of students can’t pass state exams for their grade in math and English – on a good year. During Covid he’s been doing his schoolwork, doing all his classes on a smartphone with a smashed screen.

What a year.

So I was thinking, she went around looking for Black Lives Matter signs in her nephew’s neighborhood, where the message might reach him and make some difference, and there was just one in this area of several blocks. She was saying the people in those neighborhoods don’t need people in the suburbs to put up signs; they need people to go in and connect with them and understand poverty, start to make a larger sense of community a reality. So I decided to work with her niece. The project was to get together once a month and go sketching at a series of places that are meaningful to her. I’ll make paintings to go with the sketches. Ideally we’d have our sketches and the painting and a story about a place that meant something to both of us. But mainly we both sketch. It’s a model for how to reach out and connect with someone, using art – which has the benefit of being visible – show-able. It’s the next project after the Itinerant Artist series and the Landscape Lottery.

All of these projects encourage me to go out of my way to pay attention to parts of the world I otherwise would overlook or not see. There’s a forced getting past my own interests in order to connect with something more (which I suppose is a deeper interest). Art is inherently spiritual, and this sort of builds on that, makes art practice a spiritual practice. I found what I painted in Ferguson, when I went there a year after those riots, it felt like a vigil or prayer, just being there doing a painting.

Did you see the Simone Weil quote I sent you in that material from Matthew Crawford. She said basically . . . Crawford wrote these books . . .

The World Beyond Your Head.

Right. Shop Class is Soul Craft was the first one.

Which one did you like better?

The first one because it was so out of the blue. The second one is sort of the sequel, extending his philosophy beyond craftsmanship and the trades. His way of doing philosophy was to repair motorcycles. It’s analogous to painting in the way it connects physical skill and physical awareness. Iris Murdoch was one of the most powerful references in the first book. She wrote about how art is a way of simply paying attention to something else but yourself. That’s what you were saying: egolessness, just redirecting your attention to anything but yourself. That alone is ameliorative or just a way of approaching the Good. She calls it unselfing.

Not just attending to it, but identifying with something greater.

The whole surround, the world you are in. You a part of this wholeness you’re inhabiting and just trying to be aware of it. Weil was saying that any moment of intense awareness is akin to prayer. That’s all prayer is, surrendering to something bigger. I thought that was interesting that you made that connection too.

I went through some of her stuff in my thirties and was really impressed.

Crawford talks about skilled physical labor. He talks about how, in motorcycle repair, it becomes intuitive because you get so familiar with the machine, the sounds it makes, the way it moves, whatever, that you diagnose what needs to be done, sometimes, subconsciously, by attending to physical cues without even being conscious of it. It’s partly a physical learning. Like muscle memory. It all derives from intense periods of just paying attention with care, even love.

That reminds me of one of my hates. At Mendon park, one of the workers cut down some bushes that work as habitat for certain birds and put one of these carved benches with a little awning over – it doesn’t work as shade, the bench is crudely made, and it all looks horrible. He’s crafting but there’s no aesthetics and no knowledge of the environment. I complain, but who’s to say what’s bad. I am, I guess, . . . but you know . .

These days nobody hesitates to say what’s bad. Everyone is constantly passing judgement on someone else.

Right, and that doesn’t dissolve the ego. I realize I can be very judgmental. There was this show in NYC in the 80s that was called Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

Wasn’t that Kandinsky’s title?

Yes. I was excited. But it was such bad art – well, a lot of it was weak. More to the point, the curators seemed clueless, and the writing in the review… it was clear the person didn’t know what spiritual was. It was just something theoretically defined, satisfied by certain prescribed “spiritual” criteria.

Kandinsky’s art was spiritual, but it wasn’t overtly religious. If you asked someone to do a spiritual painting, you might get an illustration of a story from the Bible. Of course that could be a genuinely spiritual painting, but not necessarily

Someone who goes to a church I sometimes go to tried to get me to paint a picture of a holy mountain in India, but he wanted saints faces floating around it and I told him I didn’t do that kind of work. I tried to persuade him that a painting of an everyday landscape could be spiritual. He just got mad and found somebody else to do the painting. The guy just wanted that and nothing else would do. That’s one end of the spectrum, but the NYC end is that spirituality is one small sub-category of abstract painting, and nothing else was.

Kandinsky didn’t mean a particular kind of painting, but that painting itself is an attempt to show what’s there in the world unseen that might become more visible through the imaginative struggle with paint.

And for him it was mainly abstract – although he did leave room for “Landscapes with Spirit”. There were no landscapes in that NYC show.

With the surrealists and the heart of abstract expressionism there was an attempt to channel spiritual energy, not just a formal innovation.

They painted as if their lives depended on it. So I met with my niece once and did some sketches and tried to get some paintings done from them. She sketched a tree and it was good. She isn’t being artistically ambitious – at least not yet – it’s mainly a chance to focus on something good or benign – in this case a tree – that she doesn’t make time for otherwise. It was just a way to get her out there sketching. She said she missed that. The first location was a church where she said she’d been baptized. And then, more recently, when her life was getting too crazy and she needed to get away, she’d slept on the back steps of this church one night.

So she got something out of the sketch that others wouldn’t. We did a sketch of houses with shadows on the roofs and the sketches were exciting, but the painting didn’t have life of the sketches. I got this photograph from that setting and I was blowing it up and just to focus I blocked off a panoramic strip of it and that strip got really interesting so now I may have this little thin painting that has nothing to do with poverty.

If you’re drawn to it, do it. Don’t stick with the plan.

<Then I contradict myself, talking about how I’m sticking to my plan, despite resistance. We talk about my marathon of taffy paintings and the way I have to postpone other things I’d just as soon be painting. I do small sections every day, a very laborious and long process but I don’t want to drop it and move on until I get the project done. A painting takes six weeks generally and when I get to week five, that’s the test in terms of energy and focus. They aren’t hyper-realistic but also not overly rough in a painterly way. You know it’s paint but you don’t see all the execution, the mark making. I’m surprised that this is what I want. I thought I wanted something else in the handling of the paint when I began this series.>

I don’t do much plein air anymore. I sketch and do photographs and work from them in the studio. I miss working from life. It’s different. You might change the image in ways that are poetic.

Yes. I think the people who are opposed to working from photographs, they are looking for variations you can’t help but make in the way you render what you see. Like Van Gogh’s marks. There’s no way he could get away from those marks. There’s no way a photograph could tell him to make them.

I have a selfish question. I feel I should try to do a Landscape Lottery somewhere else. I’ve done it here with good results. You get public interest. I’m trying to think of where to go next. It should be a city.

You randomize the GPS to come up with the locations.

Yes, for the Landscape Lottery the idea is to define an area – say Greater Rochester – then generate random points within that area to determine where I’ll go to paint. The first time I did it – in Tucson – I used a computer to generate random GPS points. For Rochester I used a pair of dice and six by six grids superimposed on a map of the metropolitan area, nested grids. Roll dice three times and you end up with a fairly precise location. With randomized locations you find something demanding that you might not have picked voluntarily. It challenges my preconceptions about what’s worthy of being painted, my ability to feel a sense of connection. I like the idea that “there is significance in all things waiting to be attended to.” But it can be hard to tune into.

It’s just you and the device. Not someone else saying or giving you a suggestion. The itinerant project as you and the other people you stayed with.

One of the rules I give myself for the Lottery is that at any painting stop I have to try to meet people. Particularly, if I meet a stranger, I will ask them to roll the dice – determining my next painting destination. Someone in the inner city rolls and I get sent to farmland in Hilton. The farmer I meet there “sends” me to the next stop (it happened to be the airport). And so on. It’s a way of getting to know people I wouldn’t meet otherwise and weaving these invisible connections through the community. (These people from very different backgrounds are sort of collaborating.) I would need to do it probably in a metro area with a gallery that would want to show the results.

Try Cincinnati. It’s a big art town. Manifest might be interested in a project like that.

That’s good. The heartland.

They’re non-profit. It’s a research center. They’re always looking for new ideas. They aren’t going to turn it down because it isn’t a money-maker.

I’m not really sure why I’ve made enforced randomness such a big part of my practice. Initially, with the Itinerant Artist Project, the focus was more on a way of sharing life – typically with strangers – that art made possible, especially getting outside the gallery and into their homes. The unpredictability was just a byproduct of relying on volunteer hosts. But I was drawn to the challenge of making art anywhere and being able to connect with anyone. And I’ve noticed the hosts for the IAP are self-selecting – I’ve gone all over the country, but it’s mostly been the world of middle-class white people who can afford to put me up for a night or two. When I do the Landscape Lottery, it’s different. I end up interacting with people from all walks of life. In both Tucson and even more here. One of the memorable stops was – I think I told you this – the random point was in Gates and there were all these things on the way I really wanted to paint. But I had to keep driving to get to my spot. No, not the quarry, not the railroad. . . oh it’s just a residential street. And the light’s nice. But there were a bunch of American flags and odd little houses and nothing picturesque at all. It was a Republican street. That’s not bad, but there was a vibe that I was in a place . . .

That’s funny. Democrats don’t put out flags.

There was a certain feel. I knocked on the door of the house I parked in front of to explain why I was there. I was very uncomfortable, but I told them about the project and this nice old lady and her daughter living there, we had a great time. They rolled the dice and sent me to the next place, which turned out to be Mount Hope Cemetery where her husband was buried. <Along with Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony> But then the scene I actually chose was just a mailbox on that Republican street with some old Fifties ranch house, and it ended up being a really popular image for the show. The woman who lived there came out to get the mail, and I apologized for being in the way and I said, ˜You know any artists around that I can give a sketch pad to?’ She said “my husband sketches all the time.’ Sure enough, he was coming down the road, and he looked suspicious, kind of unpleasant, but it turned out that he sketched everything, all the time. I got him to talk a little. He’d done a painting in high school, in Manhattan, which the school kept and he once went back to try to look at it and someone from the board of MOMA had bought it.

I remember that story.

I like being on my own and withdrawn but I actually enjoy making these connections. Extending who I can identify with. I can be very very left on some things and my whole family, my grandfather was a socialist who helped set up Canada’s healthcare system and my parents were activists. Everyone was so enthused about the BLM movement but Sonja and I were horrified that they were demonizing the police.

Now you have this “insurrection” and the police are heroes.

It’s just, I’ve had bad interactions with lots of police. They’re often power-hungry jerks but . . .

But you have to have them.

Try to be on good terms, at least keep open the potential to interact with them as human beings, reach their humanity.

There aren’t that many serious anarchists anymore. Where is Bakunin these days?

<Jim read from his phone Obama’s chastening comments about how unwise it is politically simply to talk about defunding police.>

As soon as someone’s camping on your lawn, you will call the police. The new District Attorney in L.A. says he isn’t going to enforce trespassing laws. As soon as someone pitches a tent on a front lawn in Brentwood, that will change. Compton too, probably, for that matter.

Strategically, when the protests started, I remember the news. Police all over the country were taking a knee. Yes, some are very racist. L.A. and St. Louis, but a lot weren’t that way. After a few months of demonizing police, that changed.

If I’m just a racist copy why should I answer the 911 call? With social media you feel as if you have to respond to stupidity with stupidity. It’s like the Goya painting of those two giants just bludgeoning each other with cudgels. That’s social media.

Almost all I watched of the Washington protests were these moderate Republican senators who had just lost Georgia and were talking about just getting along. They looked as if they’d had a conversion experience. Some of them really meant it.

Of course, they did. What happened to Martin Luther King Jr? Who is out there calling for the sit-in rather than the riot?

I have a friend, also named Dave Chappell, who is a student of Christopher Lasch and he’s now considered one of the top scholars on the civil rights movement. He’s white, but he’s . . .

But he’s really Black, like Bill Clinton?

He has an inside pass. He works so hard on that stuff. One of his books was about what made civil rights work. His argument was that it was prophetic religion that really had force and the leaders were willing to die for it. They had these high principles. The segregationists used church to reinforce their convictions but they didn’t have the same energy because they didn’t have the moral foundation.

It was the New Testament. Resist not evil. Love your enemy. It all comes from Tolstoy’s later writing when he embraced his own form of Christianity. He inspired Gandhi. They corresponded. MLK followed the example. Don’t answer evil with evil. Give love in response to evil.

Which is hard.

It’s seriously hard. But anyone can realize that if you’re sitting there in the photograph being attacked by police dogs and offering no violence in return, you’ve won. You don’t win against evil by being evil.

The movement now doesn’t have religious conviction.

It’s postmodern. It’s completely abandoned the absolute values that were undergirding the civil rights movement. Values are whatever works to seize and sustain power. Now it’s just power against power with no underlying absolute value. We have narratives, not values.

The push for justice and not being treated with bias is good but when you start pushing the police lines because you have demands based on what the people did who rioted last week and treating people like animals to get what you want – that’s not the moral high ground.

It’s Saul Alinsky not Martin Luther King, Jr. If the conservatives could wake up the same way. A hundred thousand people show up and sit down on the steps of the Capitol and refuse to leave, demand an investigation of the election. That’s a sit-in with a clear objective. Just sit peacefully and force the troops to carry them away. How would the media condemn them? That would be a way to ask for an investigation to find out whatever actually happened and move on. Everyone turns it into a struggle to the death because they want to turn the opposition into the enemy.

Well art can still save the world, Dave, right?

It’s certainly a way of sitting still and refusing to move. Wasn’t it Dostoevsky who said beauty will save the world? It’s worth a try.

Comments are currently closed.