Obscure objects of desire

Last Thursday, two days before the Michael Borremans show closed, just under the wire, more or less, I finally slipped into Zwirner to see it. I was on a quick tour of Chelsea galleries with my young friend from Ohio, Rush Whitaker—who rooms in Brooklyn with Lauren, the subject of my last post, as well as with Krystal Floyd, another young Midwesterner struggling to make it as an artist in New York. When he isn’t painting or writing letters to Taylor Swift, Rush works as a security guard at the Metropolitan Museum. He’s both a writer and an artist and a genuinely warm, totally honest individual who has learned some sort of emotional ju jitsu that turns all the negative energy around him into a fuel for contentment and generosity. He’s also kind of gigantic, at around 240 pounds of genetically bestowed body mass, with some rounded edges from the beer—all of which is to say so he can afford to be indifferent to the slings and arrows of the average day. He has nothing to prove. Still, I’m baffled at how unflappable and cheerful he is, whenever I see him. He’s completely unlike the classic, moody, self-involved egotist an artist is supposed to be. He was astute when it came to the work we looked at—we wandered through more than a dozen galleries, and glanced into many others without going in. We’d just visited David Zwirner’s adjoining gallery where Neo Rausch’s work was on display, and where I was finding Rausch’s images more and more disorienting and nightmarish, the longer I looked at them. Gazing into those scenes, you think there’s something just fundamentally, metaphysically wrong with human experience. Row row row your boat, he says, it won’t matter; life is but a fever dream. Rush couldn’t get enough of those paintings, moving up close, standing back, picking apart the physics of Rausch’s imaginary world and totally getting into it. I just wanted out of there. I wish I’d paid less attention; I would have enjoyed that work more. (The work is fine. I just didn’t want to stay in his world for long. Make of that what you will.)

Walking into the Borremans show . . . man oh man. There’s mastery and then there’s Mastery. Borremans makes it look as if he almost has other things on his mind as he dashes off these figures set in ambiguous, spare rooms, and yet the effect is uniformly elegant and refined, an Old World sense of figures so trapped in the amber of their worn out and inescapable dreams that they have no bearings, no connection to the world out on the street nor to any specific world at all other than the empty anonymous interiors they inhabit. There’s one painting of a naked figure inside some kind of stiff, geometric red gown, called The Devil’s Dress, and you smile when you see it because the body looks like the overgrown tongue for the bell—and then you realize what kind of bell the gown resembles. “More cowbell!” Rush said. I wasn’t laughing for long, though, because I was totally seduced by the incredible facility of Borreman’s brush. I was talking a week ago with another acquaintance, Arthur Dworkin, about Manet’s brushwork and he called it “almost cavalier.” I kept trying to remember a term from the Italian Book of the Courtier that I was sure described the quality Arthur meant, and somehow it resurfaced a few days later: sprezzatura. I’ll quote from Wikipedia because I’m too lazy to find a more respectable source:

sprezzatura (Italian pronunciation: [sprettsaˈtura) is an Italian word originating from Baldassare Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier, where it is defined by the author as “a certain nonchalance, so as to conceal all art and make whatever one does or says appear to be without effort and almost without any thought about it.” It is the ability of the courtier to display “an easy facility in accomplishing difficult actions which hides the conscious effort that went into them” Sprezzatura has also been described “as a form of defensive irony: the ability to disguise what one really desires, feels, thinks, and means or intends behind a mask of apparent reticence and nonchalance.”

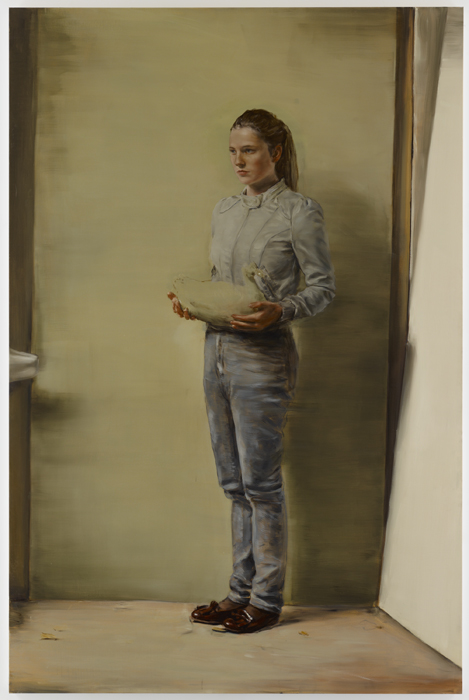

Jackpot. His technique, his world: sprezzatura. His work has an effortless, almost unfinished quality that suggests quick and gifted execution, though when he describes how he works, it’s nothing even close to easy. He’s the heir of Manet and Sargent and he’s closely aligned with Richter, in the way he leans on photography, the way he renders hair, and in the uncertain, middle light of his scenes, as if you are seeing how things look through an antique lens or from a distance of seventy years. These recent paintings have dialed back the overtly surreal elements of his earlier work, and they tend to stick to how things would actually look in an empty room, at least one in which that woman in the French maid’s dress weren’t missing her head. The black gloves seem perfectly indicated with about a dozen brush strokes that, up close, appear to be undifferentiated, flat patches of paint, with no variation in value at all. From the headless neck of this sexy, patient figure a thin ribbon winds upward, a pointless noose unspooling maybe from the ribbon choker that she’d tied around her throat a bit earlier, back before her head disappeared. The most stunning figure in the show is Girl with Duck: a young, beautiful woman holding a wooden duck that, again, is indicated by almost nothing but canvas thinly washed with oil, no detail, nothing but an outline of a duck—yet it seems to float weightlessly with its own ghostly volume and shape between the girl’s hands. You can feel it in her hands. Her tight long-sleeved blouse, and her fashionably skinny jeans, faded and worn, is evoked with more thin coats of dull blue, the brushwork completely visible and seemingly spontaneous, yet the effect is vividly real. Her tasseled cordovan loafers, as preppy as can be, show almost no detail whatsoever up close, and yet they shine and grow richer in color as you step back. She looks like some fragile, privileged and dutifully hip young princess, turning her diligent gaze into the light source, lovely and innocent. It’s a dream, without any indication that it’s anything but a snapshot of the artist’s own daughter caught while absconding with a faded decoy from the family library. The entire show seems to have been constructed out of three tubes of oil—ultramarine, some kind of dull red, and a warm yellow—manipulated with a bit of white here and there. Such a narrowly restricted palette gives Borremans the ability to maintain the sense that all of the individual paintings are windows offering slightly different views into the same fugue state. He offers up astonishingly convincing images unified by their simplicity and his narrowly restricted palette, figures that suggest a patrician limbo that looks alluringly spooky and serene.

Comments are currently closed.