The magic of the everyday, domestic, and mundane

Tangible Things, invitational group show at Main Street Arts, Clifton Springs

Main Street Arts invited me to show some of my taffy paintings in its current exhibit, Tangible Objects, along with the work of six other artists who are experimenting with form and materials, and whose work in many cases evokes commonplace, overlooked objects. In other words, Bradley and Sarah Butler recognized that someone who tries to bring forth the sense of a world in a couple pieces of salt-water taffy would be right at home with these others: all of us are exploring the formal opportunities afforded by the most humble, vulnerable objects most would consider insignificant. In other words, the spirit of still life painting hovers throughout the show: the beauty and resonance of the everyday, domestic, and mundane. I was also delighted to see my sense of being haunted by color field painting (in my candy paintings) is echoed a bit in the work of one of the other artists, Myung Urso, whose materials are fabric and paper. It’s a great show, and the work is original, surprising and often quietly poetic and stirring.

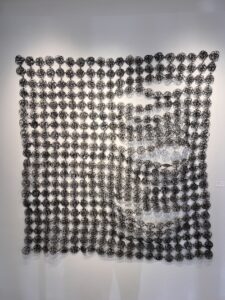

Becca Barolli, weaves stiff, annealed steel wire into shapes that suggest fabric—an old, falling-apart afghan, a long muffler—bending the wire and braiding it into these nearly immovable effigies of something far more warm and cuddly. She works long hours, rubbing CBD oil into her fingers at the end of a work day, trying to weave with steel—it’s almost a vocation the Greeks would have imagined as karmic justice for some offense against tunics. The objects suggest petrified remains of what once nurtured  comfort and life, but they aren’t morbid, nor depressing. Instead, the immense, repetitive effort, the meditative devotion required to transform the body of supple, humble things into art gives them a mysterious totemic after-life. The contrast between the delicate, original object, and the work based on it, impervious as chain mail, accentuates the gap between the medium and what it represents as well as the delight triggered by that gap in all representational art, fusing both sameness and difference into one perception. Barolli is a recent MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and has had a residency at Mass MoCA and has shown at galleries in L.A., New York City and San Francisco. Her practice favorably brings to mind Susie MacMurray’s, and it would be interesting to see them paired in a show some day.

comfort and life, but they aren’t morbid, nor depressing. Instead, the immense, repetitive effort, the meditative devotion required to transform the body of supple, humble things into art gives them a mysterious totemic after-life. The contrast between the delicate, original object, and the work based on it, impervious as chain mail, accentuates the gap between the medium and what it represents as well as the delight triggered by that gap in all representational art, fusing both sameness and difference into one perception. Barolli is a recent MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and has had a residency at Mass MoCA and has shown at galleries in L.A., New York City and San Francisco. Her practice favorably brings to mind Susie MacMurray’s, and it would be interesting to see them paired in a show some day.

At first, Sue Blumendale’s dresses look as if they could be worn to a party, but they’re made of archival copy paper that serves as a support for digital images of people from her ancestry: mother, father, aunts and a grandmother she never met. The dress becomes a sort of sculpted image of an absent human form, missing from inside the dress but commemorated with two dimensional images printed on the paper. The pictures of her family come from a family album. It’s intensely personal and felt, and the humble quality of the dresses has an almost Japanese quality of self-effacement, the everyday object surviving, transcending its wearer, coming into its own, and likewise, the artist herself withdrawing to let the dress shine, just as the subject, the missing person is absent inside the dress but present in the memorial pattern. It’s the transformation at the basis of all art: the individual human being sublimated into the creation. These are wonderfully realized three-dimensional images, where stylistic choices come together perfectly in a unique way. It’s lovely, intensely personal work. One wonders if someone could make a living doing cloth versions of these dresses to be worn, on commission, for people who wanted to clothe themselves with a memory. A new form of portraiture and a new line of clothing that exhibits the work anywhere, at any time.

On the walls are little rows and groupings of silver utensils by Christina Brinkman that stand out as interesting abstract objects—partly despite and partly because of their utility. Everyone is familiar with silverware, but these spoons shine like silk or brushed nickel. Like all the work in this show, there’s a human vulnerability and modesty that gives each utensil a kind of personality, cheerful and dutiful, surfaces showing the evidence of the artist’s hand and heart. If you owned a set of these serving spoons and forks they would likely hang on the wall, untouched; they seem to have created a new category for contemplation that has nothing to do with eating. Those little indentations in the trough of a spoon as empty as Lao Tzu’s hub of a wheel. His emptiness is what made the wheel move, empty but full of function; the emptiness here seems to make room only for the imagination. She is also a painter, printmaker and sculptor, and she has designed work for MoMA.

interesting abstract objects—partly despite and partly because of their utility. Everyone is familiar with silverware, but these spoons shine like silk or brushed nickel. Like all the work in this show, there’s a human vulnerability and modesty that gives each utensil a kind of personality, cheerful and dutiful, surfaces showing the evidence of the artist’s hand and heart. If you owned a set of these serving spoons and forks they would likely hang on the wall, untouched; they seem to have created a new category for contemplation that has nothing to do with eating. Those little indentations in the trough of a spoon as empty as Lao Tzu’s hub of a wheel. His emptiness is what made the wheel move, empty but full of function; the emptiness here seems to make room only for the imagination. She is also a painter, printmaker and sculptor, and she has designed work for MoMA.

Along the same lines, by throwing dark clay on a wheel, Peter Pincus fashions vessels that seem to embody the human craving for touch. The matte surfaces of his pots and urns require careful handling because touching them can alter the surface: these perfectly shaped objects have no skin, as it were, no armoring glaze, and though their dark curves seem infused with mystery and reserve, they are, in a sense, naked and exposed, completely open to their surroundings. It’s this fusion of opposite qualities, that makes then so attractive, magnetic, with an aura of ancient craftsmanship. Pincus teaches in the School of Art and Design at Rochester Institute of Technology.

Along the same lines, by throwing dark clay on a wheel, Peter Pincus fashions vessels that seem to embody the human craving for touch. The matte surfaces of his pots and urns require careful handling because touching them can alter the surface: these perfectly shaped objects have no skin, as it were, no armoring glaze, and though their dark curves seem infused with mystery and reserve, they are, in a sense, naked and exposed, completely open to their surroundings. It’s this fusion of opposite qualities, that makes then so attractive, magnetic, with an aura of ancient craftsmanship. Pincus teaches in the School of Art and Design at Rochester Institute of Technology.

The love for a family member, her grandmother, inspires Anna Sprague’s constructions, ostensibly jewelry, though the little three-dimensional imaginations look at home framed behind glass. She grew up in Cleveland and her experience of nature informs what she does, so it’s fitting that she resides and works in Rochester now, because the natural terrain here is more or less the same as upper Ohio, full of glacial undulations—rivers, lakes, woods and fields, wildlife. She arranges a cluster of lentils in an oval, and they look like metal filings aligned in a force field, or a scrum of ladybugs, in coordinated formation, patterns strange and soothing at the same time at such a small, intimate scale. It’s also as if you are looking down at a geode turned inside-out, prickly but with edges and points safely blunted. In either case, it’s as if you’re seeing something ordered by nature rather than human artifice.

constructions, ostensibly jewelry, though the little three-dimensional imaginations look at home framed behind glass. She grew up in Cleveland and her experience of nature informs what she does, so it’s fitting that she resides and works in Rochester now, because the natural terrain here is more or less the same as upper Ohio, full of glacial undulations—rivers, lakes, woods and fields, wildlife. She arranges a cluster of lentils in an oval, and they look like metal filings aligned in a force field, or a scrum of ladybugs, in coordinated formation, patterns strange and soothing at the same time at such a small, intimate scale. It’s also as if you are looking down at a geode turned inside-out, prickly but with edges and points safely blunted. In either case, it’s as if you’re seeing something ordered by nature rather than human artifice.

In some ways I felt closer to Myung Urso’s creative vision than anyone else in the show. She works with hand-dyed ramie fabric, paper pulp, pigment and paper board. Her most interesting pieces in the show were three-dimensional collages inspired by her observation of geometric shapes in scraps of fabric leftover from her previous constructions. She will build a box that serves as a sort of minimalist, geometric structure, like a little Bauhaus home without windows or doors or roof, cladded with half-moons or wavering rectangles. Again, the fusion of opposites, makes it come alive—as in the hard-soft contrast in Barolli’s metal fabric. And in this case you want to handle it, the soft nap of the fabric, the subtle colors. One thinks of Stella and especially Klee, and, as with everything in the show, there’s a humble freshness, a vulnerable refusal to make big statements, but a kind of meekness as a virtue that infuses her work and makes it deeply appealing. It’s a spirit that hovers throughout the entire show.

In some ways I felt closer to Myung Urso’s creative vision than anyone else in the show. She works with hand-dyed ramie fabric, paper pulp, pigment and paper board. Her most interesting pieces in the show were three-dimensional collages inspired by her observation of geometric shapes in scraps of fabric leftover from her previous constructions. She will build a box that serves as a sort of minimalist, geometric structure, like a little Bauhaus home without windows or doors or roof, cladded with half-moons or wavering rectangles. Again, the fusion of opposites, makes it come alive—as in the hard-soft contrast in Barolli’s metal fabric. And in this case you want to handle it, the soft nap of the fabric, the subtle colors. One thinks of Stella and especially Klee, and, as with everything in the show, there’s a humble freshness, a vulnerable refusal to make big statements, but a kind of meekness as a virtue that infuses her work and makes it deeply appealing. It’s a spirit that hovers throughout the entire show.

Comments are currently closed.