Spirituality at The Armory Show

Le bapteme, Marc Padeu, 78″ x 110″

On Saturday, I wandered lonely like a cloud through The Armory Show, at the edge of Hudson Yards. That domineering real estate venture is the child of our precarious finance-driven economy. It’s a forbidding, crystalline, Antarctic Fortress of Solitude rising up along the river, with Dubai-like heights so reflective its towers almost disappear against the sky. Across the street, a honeycomb of gallery booths spread out in uniform ranks inside the equally glassy, tourmaline facets of the Javits Center. (By contrast with the glass towers, the Center looks more like an enormous multi-story greenhouse.) Inside, at this annual pop-up art mall, rows of booths gave birth to another seemingly endless grid of tight little alcoves as I slowly made my way through the maze, swiveling my head in all directions, trying not to miss anything, as if riding through Pirates of the Caribbean.

The beautiful people were there in abundance, trying to look as chill as the champagne in ice buckets beside their plush chairs. So much money, but how much of it was being spent? I don’t know the break-even point for a gallery—how much needed to be sold to make a profit after the fee for a booth—but few of the people staffing these booths looked light-hearted. Most had a selection of work from their roster, while quite a few staked their investment on a solo show of only one artist. The solo shows were invariably the most interesting.

The free market is a necessarily brutal place, even at this lofty level. A corner bodega probably has an easier time turning a profit than many of the souls who must spend months preparing to ship this costly work overseas and put it up for sale at a fair. Represented were 250 galleries from around the world, but after an hour of walking, it felt like far more. It was often depressing, so much of it a cavalcade of disposable and over-hyped art. But that isn’t far from the experience of walking through Chelsea and ducking into one gallery after another. New York City is changing and has been for many years now. I miss being able to wander into Danese-Corey and never being disappointed. I miss OK Harris downtown. I also miss the Half King. And Hi Fi in the East Village. And the lines outside the Upright Citizens Brigade on 26th. All gone. Fine, so one is a restaurant, and another is a little bar/music studio, and another a school of improv, but they are similar disappearances of the past decade and were small bastions of quality or history or what will probably be considered Old New York in only a few years. Manhatttan needs another Maeve Brennan or Joseph Mitchell to document this metamorphosis, this infiltration. You feel as if you’re watching from the shore as art rides the froth of a giant wave of international money sweeping aside graceful little figures who managed to stay vertical on economic swells of smaller, more human dimensions. (There are notable survivors, like Arcadia Contemporary, whose scale is in all things extremely human. It didn’t need a booth at this show, because it is killing at its SoHo location, having sold out its entire new show at the opening on Thursday.) So it can still be done, old school, if the goal is to make enduring art rather than spectacular profits.

Dave Hickey had a vision of how the art world ought to work, imagining terraces in the Renaissance where sellers traded collegially with buyers desperate to own a particular painting—someone who just had to have it, because it was alluring and beautiful, regardless of any other consideration. It was how he wanted the commerce of art to work, fueled by the desire, charm, delight, the freedom to make art and freedom to buy it out of love, not as an investment. He lived long enough to see the phenomenon of the art fair, and he must have felt conflicted about it. It all works as he wanted—but it was hard to experience the sort of surprise and awe he celebrated as the heart of the enterprise. On Saturday, a small percentage of the work on view was arresting enough to break through the sensory overload and make me want to stop and gaze at it for more than a couple seconds, never mind getting to the point of wishing I had the ducats to own it. So little of it made me ask with wonder and admiration: how did she do that?

Some did, though.

In a few instances, I asked that question with astonished wonder. In a few booths I found evidence that great painting is still alive and well and selling. Looking at Hyperallergic’s review, now that I’m back home, I realize that I gave up too soon in a few cases—but what I found in my quick tour justified the cover charge. One painting even brought tears to my eyes: a first for me. Within just the past few weeks, I was telling a fellow painter that no painting had ever made me cry, unlike music and movies and books. I stand corrected.

Early on, in a couple instances, I found relief in work from the past represented at various galleries. Galeria de Arte, Mexico City, offered modernist abstracts by Gunther Gerzso, who died in 2000, lyrical studies in carefully scumbled color. They brought to mind a cross between Kandinsky and Braque, the surface sprinkled with stone dust, the way Braque used sand to create a stucco-like support for his oil. The gallerist on duty said that Gerzso has never had a museum retrospective to establish the strength of his achievement. The work here showed long hours of painstaking craft, and a hum of harmonies in color and texture that reminded me of the energy one feels in the Southwest desert’s air and heat. It looked worthy of a museum show to me.

Andy Warhol, Details of Renaissance Paintings, artist’s proof, 60″ x 83″

A London gallery, Archeus/Post-Modern, offered a selection of prints from Pop and Op artists—the usual suspects, Ed Ruscha, Warhol, Bridget Riley—but in what seemed like a moment of personal synchronicity, the most prominent print on display was a large artist’s proof of Warhol’s interpretation of St. George and the Dragon, the story of England’s patron saint. I’d discovered this print only a few months ago while meandering around the Web looking for various treatments of that myth down through history. Warhol photographed and then did his thing with a detail of Paolo Uccello’s painting from 1460. It’s a mysterious, almost bewilderingly abstract image: just the face of the serenely composed but endangered woman and one wing of the dragon jutting into view. Warhol was Byzantine Catholic, and went to church on Sundays, but one rarely sees any indication of his faith in the work, and it’s pretty well sublimated here, but still present and accounted for with a touch of enchantment.

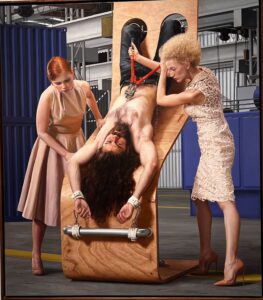

AES+F, Inverso Mundus, Inquisition or Women’s Labor #2, oil on canvas, 71″ x 62″

Across the aisle from Archeus and down a few booths I had my liveliest encounter of the day. It was a solo show of a “collective” of four expatriate Russian artists who go by their initials: AES + F. They do politically charged work in various media: video, porcelain, oil. The work is astonishingly crafted, intelligent, and wryly confrontational. The Senda gallery from Barcelona showed two large oils, reminiscent of James Valerio’s theatrically staged scenes from decades ago, yet brightly hyper-realistic and assiduously painted. In these two paintings, the artists created a re-enactment of the Inquisition, but with women dressed for a charity gala in gowns and evening wear pretending to torture half-dressed men strapped and bound to devices the artists constructed simply for the paintings. In both paintings, one of the women wields bolt cutters but not to lop off a pinkie, as we are often led to think is the wont of a Russian mobster. They appear to be engaged in a bit of ungainly man-scaping of chest hair—just a little off the top, dear, says the Baron du Charlus in the upside-down stock. The incongruity of everything in the images made me laugh but I was baffled by the corporate-looking attribution so I asked the young woman in the booth for some background. I pointed to a catalogue on the table and asked, “Is this an individual?” She came out and talked at length with enthusiasm about the group in fluent English, with a faint Spanish accent.

“They mostly work with video art and print and sculpture but very rarely do painting. This is part of an exhibition they did called Inverso Mundus, which means the world upside-down. It’s the women’s Inquisition, the matriarchy, the roles subverted, reminiscent of martyrdom scenes. Women’s work! In a very dystopian manner. AES + F have done twenty paintings. These two are the only ones left. All the others have been sold. They are really admired but really hated by the Russian government which is why they are based in Berlin. Their work clashes with the current political views.”

I asked her where she was from in Spain. She laughed and said “Michigan.” She’s living here in the states, a senior at the University of Michigan, and pointed out that she was wearing yellow (not quite maize) and blue: “It’s game day!” in that Spanish accent.

“Go Blue,” I said.

Apachaya Wanthiang, Grandmother, acrylic on canvas, 11.8″ x 15.7″

At Galleri Brandstrup’s booth, it was gratifying to see this Oslo gallery, of all things, showing the work of a young painter from Thailand whose dreamlike tropical scenes verge on expressionist abstraction. Apichaya Wanthiang applies acrylic as if it were gouache or watercolor, thin washes of paint clotted here and there with gestural accents. The resulting image hovers between something recognizable and strangely subliminal evocations of human figures in heavy foliage. Most distinctive was Wanthiang’s evident willingness to take chances, experiment, grope her way toward some kind of indeterminate closure. She’s discovering what the paint will reveal without using techniques for effects she understands ahead of time. In the smallest painting, an image of her grandmother, it looks as if the woman is flanked by three nude figures, but they are obscured and hard to fit together visually. The impact is puzzling and oneiric like a fragment from Kafka. The paintings never look done; she has simply quit working on them and the brushwork is far from elegant or polished, a passionate physical struggle with the medium.

Lauren Spencer King, Flower, watercolor on paper on panel, 12″ x 9″

Around the corner from Brandstrup, I almost missed one of the most remarkable of the solo shows from Regards, a Chicago gallery that represents few painters but couldn’t resist recruiting this one from Los Angeles, the work is so strong. It was a restrained installation of small, realistic watercolors of orchids on paper stretched over a support as if it were canvas canvas. I don’t generally like hyper-realistic work that crops a photographic image to create an abstract visual structure disengaged from its context. But in this case, Lauren Spencer King’s meditative studies have an all-over quality that, from a distance, looks gestural and abstract—if you see a photo of an installation of her small work taken from a distance, they look as if they belong in a show with Sam Francis or Helen Frankenthaler, yet up close they are amazingly accurate and three-dimensional images, capturing the curve and color of orchid petals, fields of line and form and color, lush, sensuous, and alive. It’s the work of a still mind channeling enormous energy into a small, perfectly constructed space: your own mind grows quiet just gazing at the paintings. It’s no accident that she teaches meditation.

The most powerful moment for me at The Armory Show was only a few booths away from the orchids. Jack Bell, of London, was displaying a solo installation of Marc Padeu’s large-scale scenes of African life. He’s a phenomenal painter from Cameroon, born in 1990. His work juxtaposes flatness and depth, areas of bright, almost arbitrary color within a photo-realistic armature of human figures. It sounds contrived, and sometimes it jars just slightly in its juxtaposition of brilliant colors—and echoes a bit of the feel of Kehinde Wylie’s sardonic mash-ups of Western tradition and African grit—but there’s no irony here. In one particular painting, the subject dominates the painting’s execution so that the narrative fuses with its treatment in such a way that the work stood out from everything else I saw at the fair. Le bapteme shows a small gathering of the faithful at the moment when two of the men are lowering a convert into the water for her baptism and a new life. The structure of the figures brings to mind Caravaggio: the foreshortening of the bodies and the way in which everything is arranged in a tight triangle that teeters on the fulcrum of one man’s leg, sunk into the brown water. The triangle is about to tip to the right as the woman sinks into the water, and then tip back as she comes up for air—the rhythm of a metronome, the passage of time, implicit in the arrested movement. Everyone wears white and the color scheme is highly restrained with a pale, yellow sky and flattened shapes for leaves in the background. The paint is applied in ways that simplify detail into general areas of uniform color, but without distracting from the illusion of depth and realism—the way Estes applied paint on a much smaller scale and more complicated patterns of marks, but Padeu is playing more with the tension between flatness and the illusion of depth.

All of this technical skill, though, is in service to a vision of goodness that, to me, is more powerful and accurate and effective in showing the nature of Christianity than most religious painting from the present and past. Piero’s Resurrection and Virgin Enthroned with Four Angels are rare, amazing and powerful paintings, for example, but they seem remote from the experience of faith and love. This image embodies in narrative form the experience of the faith it’s depicting: two strong men cradling the uncertain woman as she slowly goes under, ready to pull her back up. It’s almost the choreography of a waterboarding, but with everything reversed and opposite, blessed. The painting conveys the concentration and care in the men’s faces, the way in which the hands of all three are knotted together at the center of the painting, the individual and her community unified in this ceremony, in her surrender, the life-changing moment itself and how they are all bound together in this transformation of kindness, hope, and joy. None of this is conveyed the way a European would show it now, with a cool post-modern take on a religion Europe would just as soon discard. Africa is another story. I stood for a long time in that booth unable to look away. Just the fact that this deeply serious image, this tribute to simple human goodness and love, existed here, in a contemporary art fair, was incredibly moving. It makes my eyes fill up with gratitude even now.

Excellent, Dave! A rewarding read and there’s a lot of vicarious enjoyment in seeing the show through your eyes and philosophical/cultural framing. Maybe it was the Warhol that triggered an unlikely association, but I had a brief feeling of being Dante led along by Virgil. I wonder what those two would have made of the Armory Show… and the Art world in general? Nice to be reminded of various reasons not to abandon all hope.

Funny. Not Beatrice but Virgil considering the realm. Thanks Jim. New York City is never boring.