Mysterioso

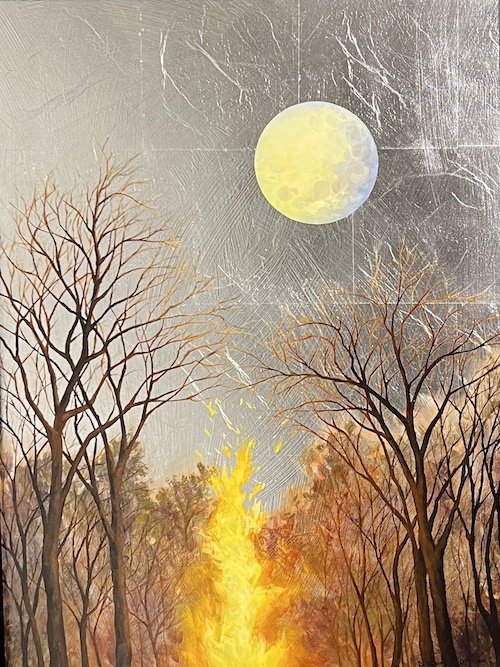

Bonfire Moon, Bridget Bossart van Otterloo, oil and silver leaf on board.

At Oxford Gallery many of the participating artists responded to the theme of the new group show—Spellbound, the Art of Mystery—with compelling work.

When I first walked through the gallery, I passed a welded steel raven from Wayne Williams with a cursory glance at the bird, but then on a second tour of the show, I paused and looked at it from various sides and began to absorb the dignity of the crusty, ruffled creature. It began to remind me just a bit of Donatello’s Lo Zuccone, a prophetic  interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible.

interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible.

Anthony Dungan’s large abstract acrylic on canvas, Saucerful of Secrets, almost side-by side with the raven, represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.

represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.

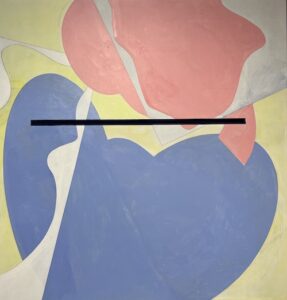

At first glance, William Keyser’s Inexplicable Lacuna appears to be a joyous pastel homage to a Matissse cut-out or one of Milton Avery’s women assembled with flat, simplified color. Yet it has a mysterious dark black line stamped  across the center of the image that seems like a salute to the void of the existentialists. With a little study, you realize the painting isn’t done on canvas and the black line is an opening cut from the sheet metal he used as a support. The cut is like an enormous mail slot, into which you deposit your hopes and dreams, wondering whether they’ll disappear in there or get delivered. It’s one of the most arresting and lovely pieces in the show.

across the center of the image that seems like a salute to the void of the existentialists. With a little study, you realize the painting isn’t done on canvas and the black line is an opening cut from the sheet metal he used as a support. The cut is like an enormous mail slot, into which you deposit your hopes and dreams, wondering whether they’ll disappear in there or get delivered. It’s one of the most arresting and lovely pieces in the show.

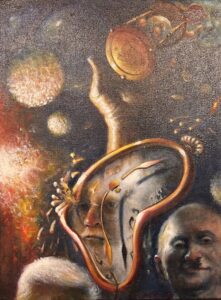

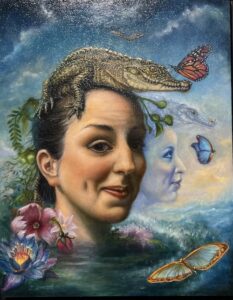

Partners in life, Tom Insalaco and Debra Stewart, paint in distinctly different ways. Yet this time, they have contributed smaller, intensely realized visions that feel familial. Insalaco’s is characteristically dark but this time prismatic, almost sparkling with a cheerful equanimity about the fleeting quality of life. In You Tell Me, he depicts the passage of time, his own face serving as the face of a melting clock—Salvador Dali hovers in an upper corner—everything pointing toward evanescence, tempis fugit. Yet the glittering eyes look as cheerful as the eyes in the Yeats poem. Stewart’s masterful dreamscape shows another cheerful woman, a contemporary Nereid maybe, rising from the ocean, with a miniature alligator perched on her head and a butterfly alighting on the alligator’s snout. Mysteriosa is a blue aquatic reverie, intricate as a jeweled Swiss watch, wonderfully timed for viewing when snow has returned to Western New York.

melting clock—Salvador Dali hovers in an upper corner—everything pointing toward evanescence, tempis fugit. Yet the glittering eyes look as cheerful as the eyes in the Yeats poem. Stewart’s masterful dreamscape shows another cheerful woman, a contemporary Nereid maybe, rising from the ocean, with a miniature alligator perched on her head and a butterfly alighting on the alligator’s snout. Mysteriosa is a blue aquatic reverie, intricate as a jeweled Swiss watch, wonderfully timed for viewing when snow has returned to Western New York.

One of the most popular paintings in the show—several people told me it was their favorite—was an unusual, idiosyncratic vision of a bonfire under a full moon. Bridget Bossart van Otterloo created a simple, nearly symmetrical nightscape that looks as bright as noon. This reversible quality of light in Bonfire Moon (above) alone recommends it as a unique achievement. With only four elements—sky, moon, bare trees and a fire that bisects the painting—she builds an image that has the simplicity and power of a logo or ideogram. From a distance, the way the fire shimmies upward toward the sky, it looks briefly like a river reflecting a sunset—giving the whole scene an inverse appearance, a sun dropping through a haze, lighting up the water. Then you realize it’s night and the water is fire and the moon isn’t the sun. What makes it work is that she’s painting in oil, but using silver leaf on board for the sky. The shine of the silver, the way it shifts in value as you move, provides the perceptual hinge for those two opposing impressions of day and night. What ought to be a slightly spooky scene feels infused with intense, radiant energy. The image pulls you closer to the warmth and life of that fire and the ubiquitous light of a full moon.

One of the most popular paintings in the show—several people told me it was their favorite—was an unusual, idiosyncratic vision of a bonfire under a full moon. Bridget Bossart van Otterloo created a simple, nearly symmetrical nightscape that looks as bright as noon. This reversible quality of light in Bonfire Moon (above) alone recommends it as a unique achievement. With only four elements—sky, moon, bare trees and a fire that bisects the painting—she builds an image that has the simplicity and power of a logo or ideogram. From a distance, the way the fire shimmies upward toward the sky, it looks briefly like a river reflecting a sunset—giving the whole scene an inverse appearance, a sun dropping through a haze, lighting up the water. Then you realize it’s night and the water is fire and the moon isn’t the sun. What makes it work is that she’s painting in oil, but using silver leaf on board for the sky. The shine of the silver, the way it shifts in value as you move, provides the perceptual hinge for those two opposing impressions of day and night. What ought to be a slightly spooky scene feels infused with intense, radiant energy. The image pulls you closer to the warmth and life of that fire and the ubiquitous light of a full moon.

You’ll find the most amazing merger between keen observation and a simplified uniformity in mark-making in Todd Chalk’s Mysteries of the Seas. On one level, it’s a landscape of sky and whitewater where the scene is stacked in roughly assembled, interlocking tiers, like field stones in a wall. The eye descends from the streaks of last light in the sky to the horizon of distant mountains, then to the different levels of the river flowing toward the viewer, swirling down and forward. Or . . . it’s a view of the ocean with swells in the foreground, one wave already broken at your feet and the water being sucked back into the sea for the next swell, while what seemed distant mountains are simply promontories of the storm-pushed water seen from far away. The rough weather is done, but the sea still rocks and rolls. The painting also works, at first glance, as a flat study of cool and warm tones applied in flowing marks and watery fault lines that evoke detail and form without specifying anything, a field of continuous color orchestrated like music. Past the age of 90 now, Todd Chalk is at the peak of her powers.

Chalk’s Mysteries of the Seas. On one level, it’s a landscape of sky and whitewater where the scene is stacked in roughly assembled, interlocking tiers, like field stones in a wall. The eye descends from the streaks of last light in the sky to the horizon of distant mountains, then to the different levels of the river flowing toward the viewer, swirling down and forward. Or . . . it’s a view of the ocean with swells in the foreground, one wave already broken at your feet and the water being sucked back into the sea for the next swell, while what seemed distant mountains are simply promontories of the storm-pushed water seen from far away. The rough weather is done, but the sea still rocks and rolls. The painting also works, at first glance, as a flat study of cool and warm tones applied in flowing marks and watery fault lines that evoke detail and form without specifying anything, a field of continuous color orchestrated like music. Past the age of 90 now, Todd Chalk is at the peak of her powers.

Susan Miller’s Too Long Unseen appears to be a hummock of nondescript soil in some abandoned field, a scene that only an Albrecht Durer could love, and she conveys with amazing skill the lumpy eroded face of this hump of land one would know how to find only with GPS coordinates. The soil sends off prickly quills of vegetation and over the top of the berm she populates the surface with vegetation that looks almost photographic but is achieved by seeming to rely on the way watercolor resolves into squiggly rivulets thanks to the yupo paper. The drawing has a sepia tone that gives it a patina of deep age consistent with the Renaissance-like aura evoked by her Durer-esque exactitude, and yet when you look closely you see how she has executed the drawing with an gestural assurance and spontaneity akin to classic Chinese or Japanese painting. It’s remarkable.

Susan Miller’s Too Long Unseen appears to be a hummock of nondescript soil in some abandoned field, a scene that only an Albrecht Durer could love, and she conveys with amazing skill the lumpy eroded face of this hump of land one would know how to find only with GPS coordinates. The soil sends off prickly quills of vegetation and over the top of the berm she populates the surface with vegetation that looks almost photographic but is achieved by seeming to rely on the way watercolor resolves into squiggly rivulets thanks to the yupo paper. The drawing has a sepia tone that gives it a patina of deep age consistent with the Renaissance-like aura evoked by her Durer-esque exactitude, and yet when you look closely you see how she has executed the drawing with an gestural assurance and spontaneity akin to classic Chinese or Japanese painting. It’s remarkable.

Nearly everyone contributed equally accomplished and interesting work including Bill Stevens, Bill Santelli (from his series of In the Humming Air paintings), Jean Stephens, Daniel Mosner, Kate Timm, Ray Hassard, Chris Baker, Jim Mott, Sari Gaby, Jack Wolsky, Sharon Gordon, Elizabeth Durant, Susan Miller, Phyllis Bruce Ely, Fran Noonan, Jacquie Germanow, Doug Whitfield, Richard Jenks, Ryan Schroeder (a small piece that does remarkable, eerie things with resin), and Amy McLaren. It’s impossible to do justice to every piece, each of which is worth a long look. It’s a fantastic show.

Comments are currently closed.