Archive for the 'Uncategorized' Category

October 27th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Emerald Light, Elise Ansel, 2017

Cause to celebrate. Another Elise Ansel show, Time Present, at Danese/Corey already, a bit over a year since her last solo show there. November 2 – December 20, 2018 Opening Reception: Thursday, November 1, 6-8pm.

October 16th, 2018 by dave dorsey

My two jar paintings at Wausau MOCA last week.

I was honored to have Frank Bernarducci select my work for the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art’s annual juried exhibition this year. Out of respect and gratitude, I decided to attend the opening last week in a show of support for the fledgling museum. It was founded only a year ago. Its first annual, national show last year was chosen by Alyssa Monks. I hadn’t been aware of this opportunity until Bill Santelli emailed me a notice that Wausau MOCA was accepting entries for the fall. I’d been visiting Bernarducci’s midtown gallery for years on visits to Manhattan, and I welcomed the opportunity, if I got into the show, to exchange a few words with him in this less pressurized setting.

“The City Has Stories to Tell”, John Hylan

Not surprisingly, most of the work was masterful, executed in highly sophisticated ways. When you see the actual work at a show like this, it’s chastening to see, up close, how many individual paths there are toward mastery of a particular medium–it’s always humbling to see how good other painters are. As traditional as some of their methods were, the show felt ahistorical—the work didn’t look as if it had been transported into the present from any point in the past but it also, to its credit, didn’t appear to be striving for any sort of illusory cutting edge. Because Bernarducci has been selling contemporary realist painting for years in Manhattan, I anticipated it would be weighted toward representational and highly realistic work, which it was, but I was surprised at how much the work emphasized the human figure and in ways accessible to most people with or without a grounding in art or art history. You didn’t need critical commentary to love this work, but occasionally it helped, and slow, repeated observation deepened my appreciation for many of the pieces. The winning oil painting, Cindy Rizza’s Lineage, depicts the artist herself nursing her baby, sitting on a worn quilt—about as far from cosmopolitan hipster ironies as one could get. It’s a beautifully rendered vision of the most fundamental and central relationship in human life, and it served as the touchstone for the entire show. The exhibition offered an astonishing array of technical prowess in the service of a quietly jubilant, affirmative vision of human thriving. The mood was one of warmth and love and intense vitality—with some notable exceptions, including one painting of a protester tossing a Molotov cocktail and a solemn image from Geoffrey Laurence of a seated woman quietly waiting to be transported to Auschwitz.

“Departure,” Geoffrey Laurence

These reminders of social injustice were almost anomalies here. If there’s such a thing as spiritual abundance, this show was an homage to it. Photorealism was well-represented, and hyperrealism, but even in these genres, the feel of the work was affectionate and idiosyncratic—not cool and sleek and impersonal. The show demonstrated that traditional techniques and straightforward representation are firmly established, once again, as a fully contemporary way to make art. Everything in the show felt as vital and new and fresh as anything I could see tomorrow on a drive into Chelsea, maybe because a sophistication about principles of design was so prominent.

David Hummer, the director, is laboring mightily—as so many are having to do now—to find a way, economically, to give the people of his region access to contemporary art from around the country. He spoke about his remarkable and impressive plans for next year, mentioning the involvement of Vincent Desiderio and Bo Bartlett, among others.

“Listening to Silence,” Ali Cavannaugh

The power and honesty of the show Bernarducci selected made me feel slightly abashed about my insistence that art works subconsciously and directly, in ways that don’t depend on subject matter. There was much implied narrative on view in Wausau, and it was powerful. Much of that power derived from the way it was painted, yet content mattered at least as much. One could use a show like this as evidence for an argument that art’s other greatest virtue, beyond the subconscious disclosure of a world, is to make visible what makes us human in the most obvious way possible, by depicting human beings. This show demonstrates you can put aside most of modernism and much of what has come afterward and still get this job done perfectly, without losing anything important in the process, including relevance to the contemporary world.

I did get a few minutes to talk casually with Bernarducci. I’m surprised to say that his manner, his kindness and geniality and unassuming role at the event were endearing. Somehow I’ve never thought to use that adjective to describe an art dealer until now, but it was exactly the impression he made. I suppose I could have arranged to speak with him in the past on a visit to his previous Midtown location, but somehow in that setting I would have felt as if I were getting between him and the ongoing fight to stay afloat that galleries face now in Manhattan. (Something they have in common with museums in Wausau, Wisconsin.) I got to know him a bit between his absorbed bouts of texting–the pressure of his life in New York followed him to the Midwest thanks to his smart phone. He said he’d gotten married in Wisconsin and he enjoyed coming back, though he was a clearly a New Yorker. He talked a bit about the economic battle for gallery owners in Manhattan and his recent new venture downtown, and he said he’d be happy to sit down and speak with me at more length on a visit to the city, with enough notice. (Afterward, I thought I should have assured him I could use a siren to give him time to find shelter, if that helped. Some people might take me up on that.) He won me over with his refusal of the spotlight when it came time to announce the prize winners, along with the look of near-anguish on his face when he said that deciding on the winners was one of the worst experiences of his life. He was not being hyperbolic. It was obvious that he hated having to eliminate all of us who didn’t make the cut for an award. Just mentioning it the way he did seemed to drain him. He struck me as a good man, fighting the good fight from his corner now in Chelsea, with nothing guaranteed, even after his decades in the business.

“Ivet,” Shane Scribner

He came to the right place: Wisconsin itself struck me the same way. It’s a long way from Silicon Valley and Brooklyn, but it’s holding its own. Wausau was a picturesque town that looked surprisingly new—as if a lot of what I saw had been developed within the past ten or twenty years. Wages aren’t quite as high as the national average there, but it had the aura of a small city with a fairly vibrant local economy, in a hilly setting that was even more beautiful with its foliage near peak autumn color.

But what struck me most deeply about the state was a moment on the highway as I drove north to attend the opening. I flew into Chicago and drove to Wausau in a rented Nissan, listening happily to podcasts in a steam of comfortably spaced cars doing around 80 for most of the trip on Interstate 90. About halfway to Wausau, my Google Maps route turned red and traffic slowed dramatically. Here’s what was so marvelous: very quickly, the cars in the right lane began to merge into the left one, as I followed the example of the fellow ahead of me. A couple cars passed and merged ahead of us, but that was all. Soon all the drivers were slowly crawling forward in the left lane—far ahead of the need for any of us to be in one lane. The bottleneck was still well ahead of us and the right lane now was entirely open and free of cars. No one, not a single driver, was speeding down the right lane in order to get up to the most advanced possible spot for the two lanes to merge. In other words, nobody was doing what drivers in every other state seemed to have learned to do—stay in that right lane until the very last moment when you have to merge left in order to shave a minute or two off one’s drive time and cut into line far ahead of all the others who have already politely taken their place in the slow lane. The right lane seems to have become the passing lane, at least where I live, and people roll up to the red light just waiting to engage in a drag race to get ahead of as many people in the left lane after the light turns green—and the same principles seem to apply in most places on the highway when construction is in progress. But not in Wisconsin. They’re actually courteous when they get behind the wheel–more than willing to respect the place of others who have already queued up. A quarter mile of slowly moving forward with absolutely no one cutting out into that empty right lane in order to get ahead—it was almost poignant. This was civility. I’m glad I made this trip, despite the cost and the time involved. It was worth it.

October 11th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Still Life, Gillian Pedersen-Krag

There’s a funny and moving scene in Amadeus where Mozart defends his music for The Marriage of Figaro. His monarch cites good reasons for prohibiting a performance of the story: it’s immoral, degenerate and revolutionary in spirit. (The movie suggests that some might have thought of Mozart’s own personal life in those terms, on occasion.) The king fears that a performance of the opera might inspire insurrection. France is on the verge of political chaos. Austria worries about the contagion. Yet Mozart dismisses all of these considerations, and his fervor about what he’s done in his composition is entirely about the formal brilliance of his work: the libretto may be subversive, disruptive and potentially violent, but his music is the embodiment of harmony and order. He’s living on an entirely different plane from those around him, playing a glass bead game with notes, striving for transcendent harmonies, merging many voices into one melody, with a passion for conveying nothing more than the quick joy of life itself.

The king: “Figaro is a bad play. It stirs up hatred between the classes.”

Mozart: “Sire, there is nothing like that in the piece. I hate politics. The end of the second act for example. It starts out as a simple duet. Just a husband and wife, quarreling. Suddenly, the wife’s scheming little maid comes in, duet turns into trio. Then the husband’s valet comes in. Trio turns into quartet. Then the stupid old gardener comes in. Quartet turns into quintet. On and on. Sextet, septet, octet. How long do you think I can sustain that, your majesty? Twenty minutes. If that many people talk at the same time, it’s noise. Only opera can do this. But with opera, with music, you can have twenty individuals talking at the same time and it’s not noise, it’s a perfect harmony.

For him, it isn’t what anyone in the opera is saying that matters. What matters is MORE

October 10th, 2018 by dave dorsey

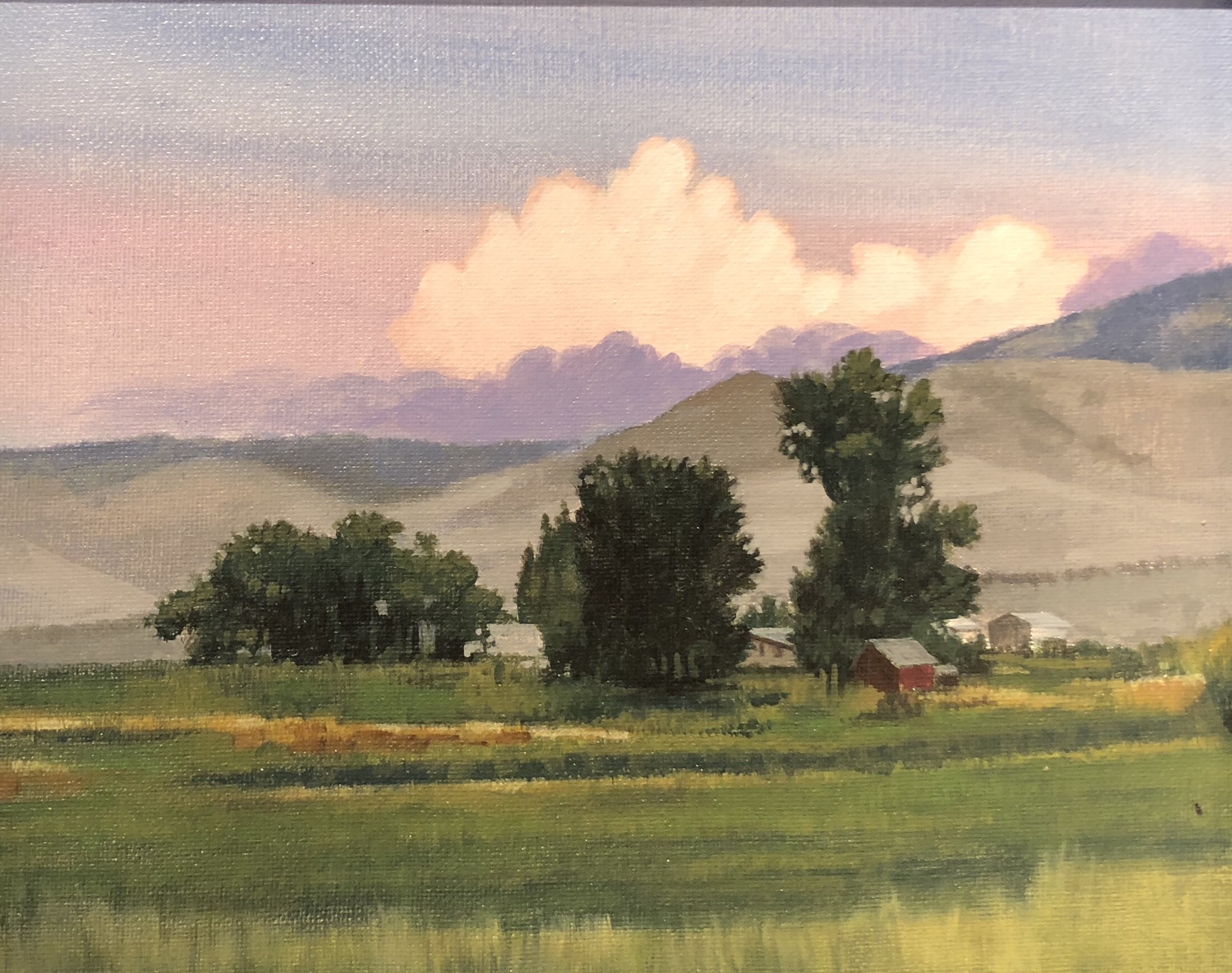

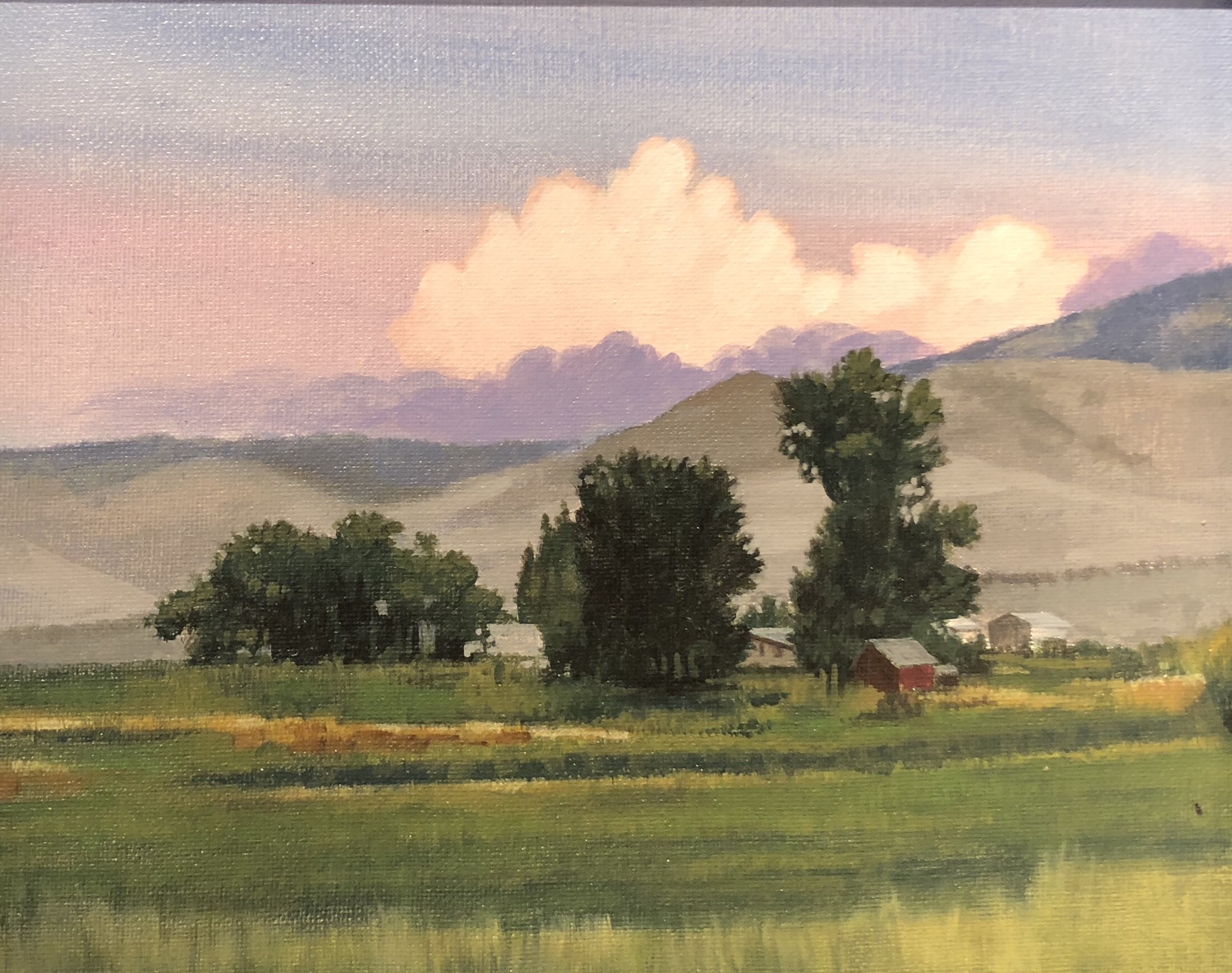

These are small, beautifully executed landscapes by Bill Finewood, currently on view in “Methods Change but the Spirit is the Same”, at the Insalaco-Williams Gallery 34, Finger Lakes Community College. It’s a great overview of his work in different mediums and styles throughout his career. These oils were stand outs in composition, color and handling of the medium, resonant with the unique light of a particular time of day and season. The show also includes a marvelously tactile and detailed drawing of a rabbit, a bit of an homage to Durer’s famous and incomparable one.

August 23rd, 2018 by dave dorsey

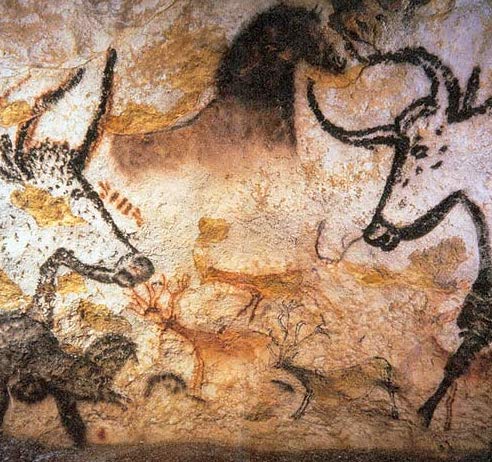

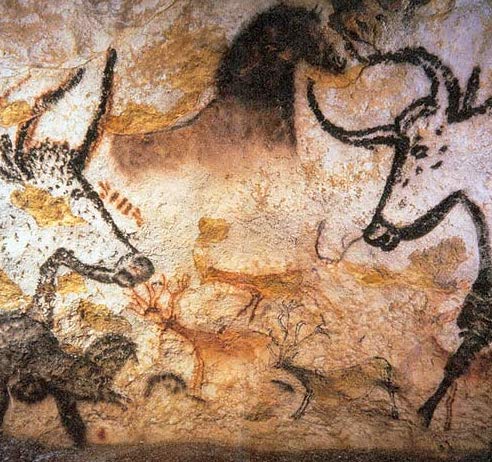

From the sixth episode of The Anthropocene Reviewed, a witty, smart podcast about almost anything from the vantage of this era in which human beings are changing the nature of the world, intentionally and unintentionally, in ways no living creature has ever done before. This is almost the entire essay on the Lascaux caves, but the second half, on Taco Bell, is just as fine and worth the visit for a listen:

From the sixth episode of The Anthropocene Reviewed, a witty, smart podcast about almost anything from the vantage of this era in which human beings are changing the nature of the world, intentionally and unintentionally, in ways no living creature has ever done before. This is almost the entire essay on the Lascaux caves, but the second half, on Taco Bell, is just as fine and worth the visit for a listen:

So if you’ve ever been or had a child you will likely already be familiar with hand stencils. They were the first figurative art made by both our kids somewhere between the ages of two and three. My children spread the fingers of one hand out across a piece of paper and then with the help of a parent traced their five fingers. I remember my son’s face as he lifted his hand and looked absolutely shocked to see the shape of his hand still on the paper, a semi-permanent record of himself. I am extremely happy that my children are no longer three and yet to look at their little hands from those earlier artworks is to be inundated with a strange soul-splitting joy. Those pictures remind me that they are not just growing up but also growing away from me, running toward their own lives. But of course that’s meaning I am applying to their hand stencils and that complicated relationship between art and its viewers is never more fraught than when we are looking deeply into the past.

In September of 1940, an 18-year-old mechanic named Marcel Ravidat was walking his dog Robot in the countryside of Southwestern France when the dog disappeared down a hole. Robot eventually returned, but the next day Ravidat went to the spot with three friends to explore the hole and after quite a bit of digging they discovered the cave with walls covered with paintings, including over 900 paintings of animals: horses, stags, bison and also species that are now extinct, including a woolly rhinoceros. The paintings were astonishingly detailed and vivid with red, yellow and black paint made from pulverized mineral pigments that were usually blown through a narrow tube, possibly a hollowed bone, onto the walls of the cave. It would eventually be established that these artworks where at least 17,000 years old. Two of the boys who visited the cave that day were so profoundly moved by the art they saw that they camped outside the cave to protect it for over a year. After World War II, the French government took over protection of the site, and the cave was opened to the public in 1948. When Picasso saw the cave paintings on a visit that year, he reportedly said, “We have invented nothing.”

There are many mysteries at Lascaux. Why, for instance, are there no paintings of reindeer, which we know where the primary source of food for the Paleolithic humans. Why were they so much more focused on painting animals than painting human forms? Why are certain areas of the caves filled with images including pictures on the ceiling that required the building of scaffolding to create? Were the painting spiritual? “Here are sacred animals.” Or, “Here is a practical guide to some of the animals that might kill you.” Aside from the animals, there are nearly a thousand abstract signs and shapes we cannot interpret and also several negative hand stencils, as they are known by art historians. These are the paintings that most interest me. They were created by pressing one hand with fingers splayed against the wall of the cave and then blowing pigment, leaving the area around the hand painted. Similar hand stencils have been found in caves around the world from Indonesia to Spain to Australia to the Americas to Africa. We have found these memories of hands from fifteen or thirty or even forty thousand years ago.

These hand stencils remind us of how different life was in the distant past. Amputations, likely from frostbite, are common in Europe, and so you often see negative hand stencils with three or four fingers. But they also remind us that the past (artists) were as human as we are, their hands indistinguishable from ours. Every healthy person would have had to contribute to the acquisition of food and water, and yet somehow they still made time to create art almost as if art isn’t optional for humans It’s fascinating and a little strange but so many Paleolithic humans who couldn’t possibly have had any contact with each other created the same paintings the same way–art that we are still making. But then again what the Lascaux art means to me is likely very different from what it meant to the people who made it.

I have to confess that even though I am a jaded and cynical semi-professional reviewer of human activity, I actually find it overwhelmingly hopeful that four teenagers and a dog named Robot would discover 17,000-year-old hand prints. That the cave was so overwhelmingly beautiful that two of those teenagers devoted themselves to its protection, and that when we humans became a danger to that cave’s beauty, we agreed to stop going. Lascaux is there. You cannot visit. You can go to the fake cave we built and see nearly identical hand stencils but you will know this is not the thing itself but a shadow of it. This is a handprint but not a hand. This is a memory that you cannot return to. All of which makes the cave very much like the past it represents.

August 9th, 2018 by dave dorsey

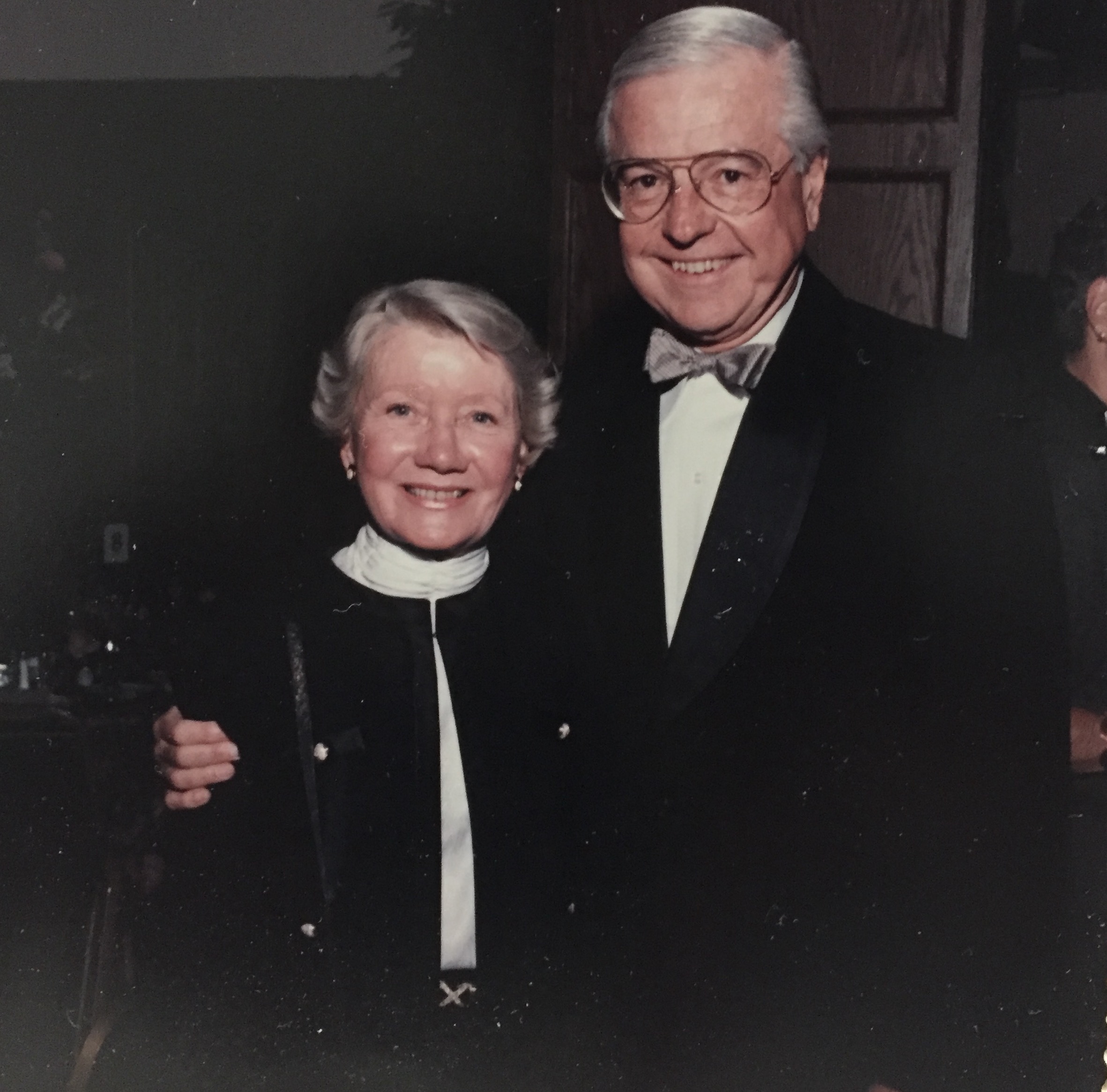

My parents, Gene and Rita Dorsey, from happier times.

I’ve been a blogger manqué for much of the summer mostly because I’ve been immersed in trying to finish the three paintings I’ve already written about—and I am on pace to get them done on time. But I’ve also been busy with my two other occupations—writing to earn money and taking care of my elderly parents. It feels odd to call my parents elderly when I, myself, will in short order be able to qualify for that demographic. Maybe sixty is the new forty, but I have a feeling that the milestones to come will cast a darker shadow on a narrowing path. Time feels as if it’s getting shorter by the day, which means I need to work harder to stay ahead of the clock, but I’m finding that the painting life is giving me lessons about my larger life as a human being, not just a painter, despite myself. The need to pay attention has become the central imperative of my life, in almost all activities. Writing still comes naturally, and I can do what I need to do—with the exception of contributing to this blog over the summer, clearly—but caring for my parents has become both a bigger challenge and a deeper reward. I find, repeatedly, that I’m choosing to see myself as a son, rather than a painter, on a daily basis for varying lengths of time. And I’m discovering that, as laborious and discouraging as it can be, I’m adapting to it. I’m changing in a way similar to what happened to me when I became a father, when I found myself willing to do almost anything to care for my kids, without resentment or complaint—no matter how it robbed me of my autonomy and personal time.

My brother, Phil, and I share the responsibilities of enabling my parents to continue to live independently in their condo in Penfield, NY, a twenty-minute drive from my home. My father lives most of his life now at a few points on the tiny map of his primarily domestic world: bedroom, bathroom, dining room, deck and TV room. He’s able, just barely, to shift his body from bed to scooter and thence to the bathroom, the living area, or the deck outside. His infirmities derive from stenosis, peripheral neuropathy, a brief TIA from which he partially recovered, pulmonary issues, and increasing effects of dementia—he is the same person as he always was, but greatly diminished, hemmed in, caged by his body and brain, though his sense of humor remains intact as do his gratitude and kindness. However, more and more his despair over his condition sparks bouts of anger or snarky critiques of those around him. Inevitably, whenever we are together I gaze directly at the future, my future and everyone’s future, and it has the effect of stripping away most of the layers of denial that all of us wrap around ourselves like comforters on a cold night. Old age and death watch me, as I watch them. We’re all dying slowly or quickly, and when you see that, what matters most in life is giving as much care to one another as possible. Occasionally, the demands of my father’s predicament test my equanimity, but most of the time I just surrender and do what both of them need and what my brother, Phil, is unavailable to do.

Yesterday afternoon, I stepped away from my canvas long enough to take a call from my mother. I had to do it on my iPad because the iPhone was MORE

July 23rd, 2018 by dave dorsey

Parquet Courts at SXSW 2013

Wide Awake, the new album from Parquet Courts, is a relief. I’d almost given up on these guys. In his production of the album, Danger Mouse has helped bring them back to their core strengths, while at the same time becoming a bit like the musical equivalent of Prozac. He makes the overall experience less discordant and much, much more enjoyable than the band’s work since their breakthrough album, but he also rounds off the edges a bit. In a few tracks, the boys hit their post-punk target with the same raw power and wit (“Do I pass the Turing test?”) that was so evident in Light Up Gold. Yet much of this pleasurably surprising album stays at a less frenetic pitch. What’s hopeful is that, in comparison with the experimental recordings they’ve been tinkering with, here they’ve kept faith with their unkempt appetite for a relentless beat, and are a little more considerate of an average Ramones lover’s needs. What I miss is the sense of their cutting completely loose, flirting with barely controlled frenzy in obeisance only to a melody and their phenomenal drummer, Max Savage. They have yet to set the crossbar any higher than Master of My Craft but they’re getting close.

July 18th, 2018 by dave dorsey

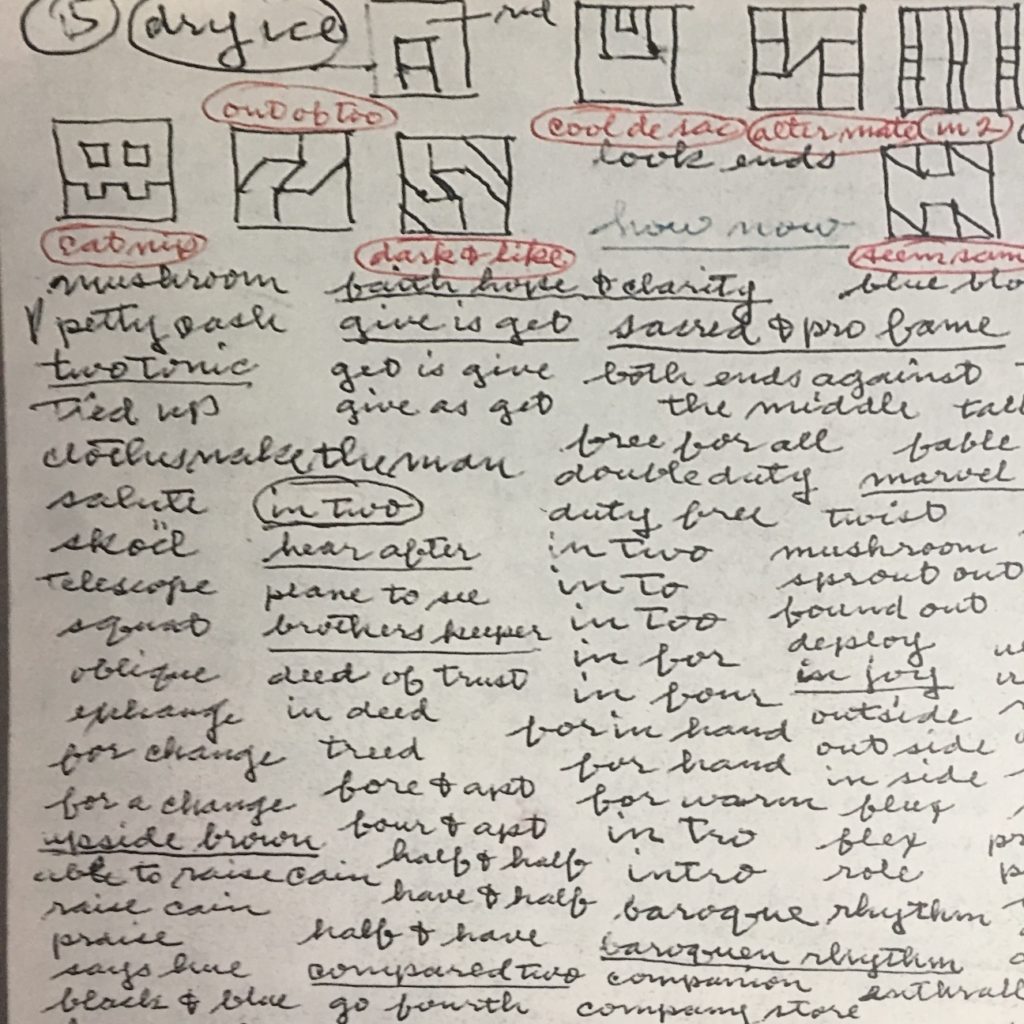

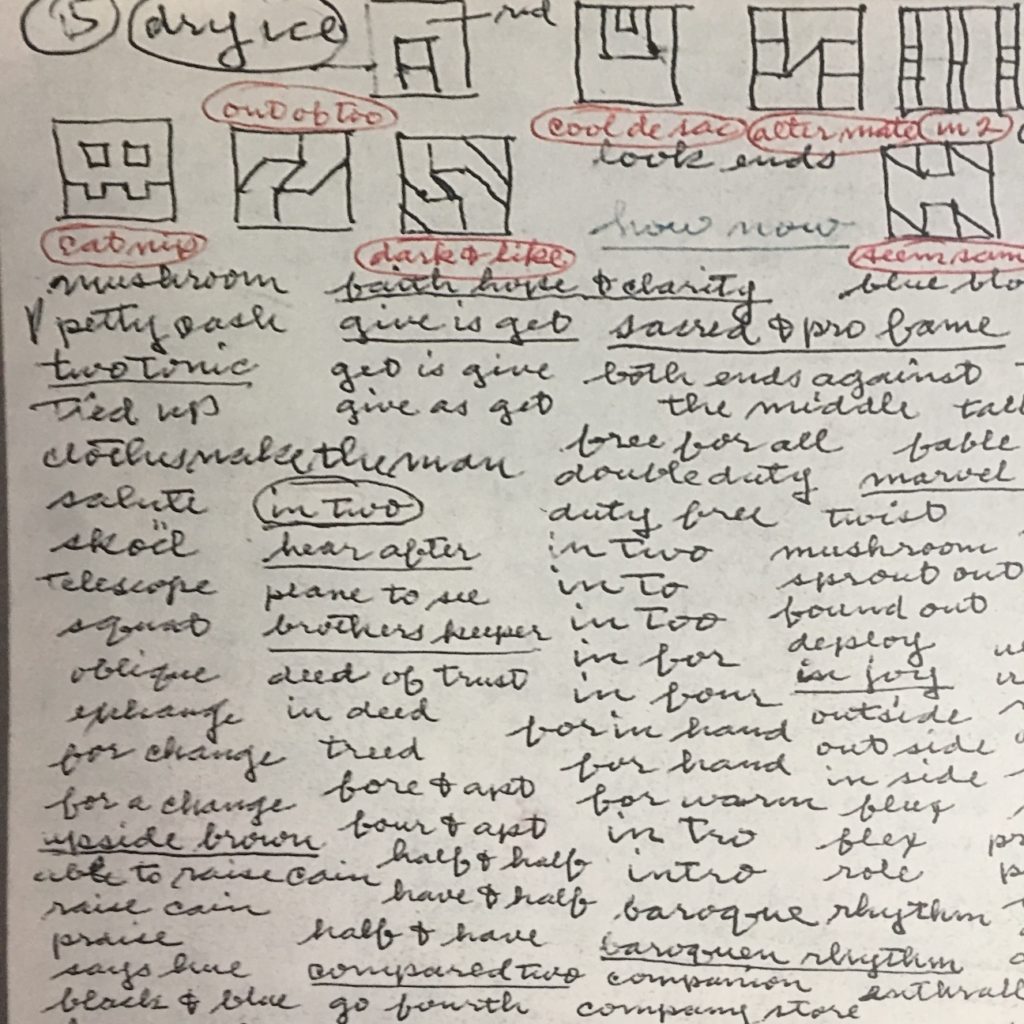

Frederick Hammersley’s notes for possible titles

To live and work by inspiration you have to stop thinking. –Agnes Martin

Frederick Hammersley was a sort of visual Taoist. Everything in his work seems to emerge out of a creative tension between polar opposites. Even his titles often depend on the polarities of a pun. If something in his work is pregnantly curved, it will be answered by razor-sharp angles elsewhere. In his organic images, the paint seems as irresistibly pure and fresh and new as tinted icing on a cake, yet it will be surrounded by a frame that looks salvaged and restored, as distressed as driftwood. These one-off, hand-crafted wooden frames—the urge to run a fingertip across them was mighty strong when I saw his work in 2011—are countered by the thin, low-profile lines of the floater frames that contain his geometric images. He worked on comparatively miniature canvases for the organic paintings and built the shadow box frames seemingly to bulk them up, and the frames work as yet another essential, polarizing element. They are almost prosthetic, a completion of the work, different from the way Howard Hodgkins integrated his frames with the work by making them a wider surface for his paint. With Hammersley, the frames are idiosyncratic, original, married to the painting rather than subordinate to it, making the painting a distinctly three-dimensional object, physical and situated in a particular place in front of the viewer’s body, a fellow traveler through time, smiling with an unspoken individual history. The painting sits inside the shallow box, without seeming to touch it, at rest, at home.

In these organic paintings, black and white wrestle as opposites often in their own tiny zip codes, yet they are segregated in such a way that their polarity is enveloped by the larger polarity between this opposing duo and the various peninsulas of luminous color around them. It’s wheel within wheel of opposing elements, smaller polarities within larger ones.

Group Insurance, Frederick Hammersley

Hammersley’s organic shapes look anatomical and informal, hand-written, as if they could be cartoon X-rays of whatever is going on inside a Dr. Seuss figure. His lines feel as recognizable as a signature. The coloring book shapes allow him to juxtapose one pure color against another. The tones glow with delight, a calmly heightened response to the experience of seeing one spot of pure color next to another. They offer understated, captive ecstasies. Their color harmonies emerge gradually as you view them. The assertive, overconfident world of so much large-scale abstraction depends on its ambitious scale. Hammersley’s luminously colored lobes huddle and fold into one another like vulnerable newborns on small canvases; they almost need their frames to get noticed.

His geometric paintings are much larger, but not all that big. The work I saw at Ameringer McEnery Yohe (now Miles McEnergy) were square, ranging between three and four feet wide, small enough to fit on the wall of nearly any American house. As David Reed pointed out in the show’s catalog, Hammersley’s work was meant to be part of one’s daily life, a domestic companion, not something to visit on “high art occasions.” The structure of his geometries seem like an entirely dispassionate pursuit, like MORE

June 26th, 2018 by dave dorsey

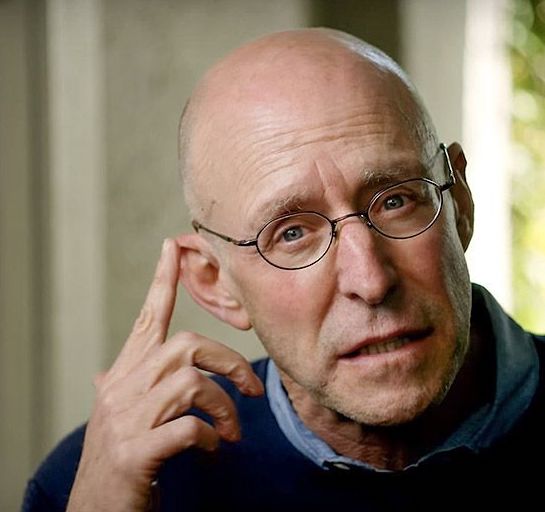

Michael Pollan (source:YouTube)

I’m reading Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind, which describes the wave of new research into psychedelic drugs. It’s in the same vein as Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, drawing parallels between what users experience and what mystics from various religious traditions said about their own encounters with transcendence. I’ve never experimented with these substances, despite pressure to do it from the other members of my garage band in high school, in which I played guitar. (They all had a habit of dropping mescaline before practice sessions.) I have no interest in trying them now. What’s compelling about Pollan’s book is that he had little interest in religion and spirituality when he began his research and was surprised by what he discovered as he got deeper into the subject. What interests me in all this is how it relates to the way in which the process of painting is a much quieter, and less dramatic, path toward a similar sort of ego-effacing state of awareness–though that phrase would hardly describe much of the higher profile art being produced now. (Critics, of course, can make the discipline even more ego-effacing . . . )

“The study demonstrated that a high dose of psilocybin could be used to safely and reliably “occasion” a mystical experience—typically described as the dissolution of one’s ego followed by a sense of merging with nature or the universe. This might not come as news to people who take psychedelic drugs or to the researchers who first studied them back in the 1950s and 1960s. But it wasn’t at all obvious to modern science, or to me, in 2006, when the paper was published. What was most remarkable about the results reported in the article is that participants ranked their psilocybin experience as one of the most meaningful in their lives, comparable “to the birth of a first child or death of a parent.”

“AS SOMEONE not at all sure he has ever had a single “spiritually significant” experience, much less enough of them to make a ranking, I found that the 2006 paper piqued my curiosity but also my skepticism. Many of the volunteers described being given access to an alternative reality, a “beyond” where the usual physical laws don’t apply and various manifestations of cosmic consciousness or divinity present themselves as unmistakably real. All this I found both a little hard to take (couldn’t this be just a drug-induced hallucination?) and yet at the same time intriguing; part of me wanted it to be true, whatever exactly “it” was. This surprised me, because I have never thought of myself as a particularly spiritual, much less mystical, person. This is partly a function of worldview, I suppose, and partly of neglect: I’ve never devoted much time to exploring spiritual paths and did not have a religious upbringing.”

“The story of how this paper came to be sheds an interesting light on the fraught relationship between science and that other realm of human inquiry that science has historically disdained and generally wants nothing to do with: spirituality. For in designing this, the first modern study of psilocybin, Griffiths had decided to focus not on a potential therapeutic application of the drug—the path taken by other researchers hoping to rehabilitate other banned substances, like MDMA—but rather on the spiritual effects of the experience on so-called healthy normals. What good was that? In an editorial accompanying Griffiths’s paper, the University of Chicago psychiatrist and drug abuse expert Harriet de Wit tried to address this tension, pointing out that the quest for experiences that “free oneself of the bounds of everyday perception and thought in a search for universal truths and enlightenment” is an abiding element of our humanity that has nevertheless “enjoyed little credibility in the mainstream scientific world.” The time had come, she suggested, for science “to recognize these extraordinary subjective experiences . . . even if they sometimes involve claims about ultimate realities that lie outside the purview of science.”

By the time Griffiths turned fifty, in 1994, he was a scientist at the top of his game and his field. But that year Griffiths’s career took an unexpected turn, the result of two serendipitous introductions. The first came when a friend introduced him to Siddha Yoga. Despite his behaviorist orientation as a scientist, Griffiths had always been interested in what philosophers call phenomenology—the subjective experience of consciousness. He had tried meditation as a graduate student but found that “he couldn’t sit still without going stark-raving mad. Three minutes felt like three hours.” But when he tried it again in 1994, “something opened up for me.” He started meditating regularly, going on retreats, and working his way through a variety of Eastern spiritual traditions. He found himself drawn “deeper and deeper into this mystery.” Somewhere along the way, Griffiths had what he modestly describes as “a funny kind of awakening”—a mystical experience. I was surprised when Griffiths mentioned this during our first meeting in his office, so I hadn’t followed up, but even after I had gotten to know him a little better, Griffiths was still reluctant to say much more about exactly what happened and, as someone who had never had such an experience, I had trouble gaining any traction with the idea whatsoever. All he would tell me is that the experience, which took place in his meditation practice, acquainted him with “something way, way beyond a material worldview that I can’t really talk to my colleagues about, because it involves metaphors or assumptions that I’m really uncomfortable with as a scientist.” In time, what he was learning about “the mystery of consciousness and existence” in his meditation practice came to seem more compelling to him than his science. He began to feel somewhat alienated: “None of the people I was close to had any interest in entertaining those questions, which fell into the general category of the spiritual, and religious people I just didn’t get.”

Later, he quotes another researcher:

“You go deep enough or far out enough in consciousness, you will bump into the sacred. It’s not something we generate; it’s something out there waiting to be discovered. And this reliably happens to nonbelievers as well as believers.” Whether occasioned by drugs or other means, these experiences of mystical consciousness are in all likelihood the primal basis of religion.

June 21st, 2018 by dave dorsey

About a week ago, Hyperallergic published a great, brief assessment of how tough it is to make a living as an artist, and it’s pretty obvious that if you want a life of luxury then you should look into investment banking. Yet the ultimate effect of the piece is heartening. Most of us are on the same life raft. On the whole, artists don’t make much. But we find ways to make ends meet and still make art. And the longer we stick with it, the happier we get. The writer, Benjamin Sutton, was reporting on a study released by Creative Independent, an offshoot of Kickstarter. The group surveyed artists in the U.S., UK, Canada, France and roughly 50 other countries.

What’s most welcome about the piece is how it actually showed that it’s possible to be serious–and reasonably happy–about making art without being able to stay solvent from the proceeds. Which means, more or less, that if you think Van Gogh was a failure, then you need at attitude readjustment, friend. Failure isn’t about money when it comes to creative endeavors.

Here were some of the finding:

- The majority of visual artists working today make less than $30,000 per year. (Average median income in the U.S. is nearly double that.)

- Only 12% of respondents said that gallery sales of their work have been helpful in sustaining their practices, and grants ranked similarly low.

- Two thirds said they had to rely on freelance work to make a living. The next largest segment do work unrelated to art for the bulk of their income.

- Half of all artists surveyed said they make less than 10 percent of their income from their art.

- Schools don’t prepare artists for a world that runs on the exchange of money–though it’s hard to see from the findings what art schools could actually do to help artists earn more. A little more preparation for how one needs to find other ways to make a living in addition to art maybe . . .

- Just under a third of respondents felt that gallery representation did little to improve their financial stability. The gatekeepers are finding it just as difficult to stay in the black as the artists themselves.

- The Malcolm Gladwell rule of 10,000 hours of practice as a threshold for mastery–in this case ten years of work–makes a difference. Artists who stick to a professional regimen for a decade earn more and find themselves much happier with the life of making art. After two decades, happiness rises even more.

June 10th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Palm Pattern #125, Edith Bergstrom, at Butler Institute of American Art

The Butler Institute of American Art, the nation’s first museum devoted exclusively to American art, is a jewel tucked way in an old, slimmed-down Rust Belt town, which was booming when America’s industrial age was in full swing. Youngstown is probably one of the communities hardest hit by the migration of heavy industry out of the U.S. and has had to rebuild since huge job losses in the 1970s. Once a city of 170,000 people, it shrank to around a third of that in the 70s and 80s. As with most cities once nourished by the Erie Canal (like the one in which I live), it has had to find ways to diversify its economy and attract and grow innovative new technology firms despite the Great Lakes climate. In the past decade, Youngstown began to stir with new economic life and because of its history as an industrial powerhouse, back when it attracted immigrant workers from around the world, it remains one of the most racially and culturally diverse cities in the nation. Flint and Detroit may get all the publicity, but Youngstown has to have been buffeted and betrayed by the global economy about as severely as any town in the world—and yet it has found a path forward to a new sort of identity and pride in itself. The Butler seems to assert a kind of unassailable character, an affirmation that a few quiet human virtues—gratitude, appreciation, taste—won’t just survive but can prevail in our current feverish media culture. It feels a little miraculous to walk into this little oasis of beauty and wisdom hidden in “flyover country,” among the ghosts of steel mills almost exactly halfway between New York City and Chicago, in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.

I delivered a painting to the Butler this past week for the Midyear exhibition by driving west through Buffalo and Erie. I was startled, when I turned onto Wick Avenue, where the museum is situated on the Youngstown State University campus. It’s a beautiful structure, a little grander in person than in its photographs, with a columned façade that looks as if it were modeled after one of Piero’s early Renaissance piazzas. After I dropped off my still life in its wooden crate, I decided to linger for a look at my destination. It was such a pleasure, I ended up staying far longer than I’d intended. It was like being introduced to someone with whom you feel a deep affinity—both the permanent collection and the current temporary exhibits were evidence of a guiding, deeply affectionate intelligence about great art. That sense of welcoming affinity is how I feel every time I visit the Phillips Collection, and to a slightly lesser degree, smaller museums like the Morgan and the Frick—as if I’m perfectly at home in the space and with the work itself. Many of the museums in cities that once thrived because of the Erie Canal offer art museums whose character is akin to the Butler’s—The Albright-Knox, the Memorial Art Gallery, The Everson and Munson-Williams Proctor. The emphasis on American Art at Butler makes it somehow feel the most companionable of them all. By contrast, this hospitable sense of belonging is what I don’t feel when I tour many galleries and some museums. The Tate Modern in London, for example, had an atmosphere of severity, an almost impersonal sense that the art on display was meant to be a rude awakening, which is fine. That’s certainly a recurrent quality in modernist and post-modern work, and there’s nothing wrong with the occasional swift kick to the head, but here, everything I saw seemed to be imbued with a sense that art can celebrate life as a welcome gift. It was moving to feel this kind of serenity in a community that has endured enormous tribulations as America’s economy reconfigures itself.

It was a pleasure that a few of the paintings I was seeing for the first time had been familiar to me from reproductions for decades–while others were unfamiliar works by some of my favorite artists. It was a delight to finally see, in person, Edward Hopper’s Pennsylvania Coal Town, James Valerio’s Ruth and Cecil Him, and Music by John Koch along the mezzanine in the museum’s central gallery. Each is an example of the painter’s mastery at its peak. They were on display along with equally powerful work by Janet Fish, Neil Welliver, Alfred Leslie, Will Barnett, Jules Olitski, Paul Jenkins, Motherwell, Avery, Gorky, Ivan Albright and Pollock. Much of the work is exceptionally good, sometimes MORE

May 9th, 2018 by dave dorsey

David Gracie, “Cupcake” Oil on Maple Plywood, 21” x 26,” 2017

I love a cupcake as an intellectually weightless subject. Make of it what you will, the less I mess with it the better off I am, both the cupcake itself and its representation. Its pleats and creases and folds crumple and smear on the trip home if you hit a couple potholes. It pretends to be the perfect little stupa of pastries, but touch it the wrong way and you start to ruin it. Like paint itself sometimes. David Gracie’s inverted cupcake seems fraught and decadent. It could be growing from a seed or spore. It appears to be floating in a dank sylvan setting, like a skunk cabbage or an inside-out toadstool, wearing its gills as a cap, but with only the smallest of stems, holding it up or maybe down. Is it levitating? The surreal aura of the scene would seem to allow it. I doubt that it would prove fruitful to spoil the mystery by asking why. It is on view at Exeter Gallery in Baltimore, which opened its doors last fall and has begun showing the work of artists as different as Gideon Bok and Erin Raedeke. I wish I’d made the trip to see the show of Paul Manlove’s paintings. (Guys, build a website. If there is one, Google is not aware.)

In a time when art galleries seemed besieged by an economy that favors the very rich, and the very famous, who all seem to prefer to show, buy and sell at art fairs–rather than the humble and traditional gallery space–you have to admire anyone intrepid enough to open a new one for business. With all the shops that keep closing their doors, others continue to pop up. Like our already bruised cupcake rising backward toward the blue sky whose cool light it reflects toward the viewer. Matt Klos, a fellow exhibitor at Oxford Gallery here in Rochester, appears to be curating shows at Exeter, owned by Noe & Amanda Detore. He’s the right guy for the job. It’s sure to be another outlet for the “perceptual painters” and maybe others (too early to tell) who deserve more recognition. The work they’ve shown so far has been fascinating and a little strange, and this new show seems to fit right in.

Here is the emailed invitation to the opening on May 12, 6-9 p.m. from Matt:

David Gracie is a painter of slow meditative works. As mechanical as his process of painting may be it is tempered by his empathy, humor, and curiosity in looking. This exhibition of Gracie’s work from over the past fifteen years marks a homecoming for the artist who was born and raised in Baltimore.

David Gracie was born in Baltimore, MD in 1978. He received his MFA from Northwestern University in 2004 and his BFA from the Hartford Art School in 2000. He has been included in exhibitions at The Museum of Nebraska Art, NE (’17), Hartford Art School, CT (‘17 and ‘09), The Suburban, WI (‘16 and ‘15), Mt Airy Contemporary, PA (‘15), The University Club, IL (‘13), The University of Missouri, MO (‘12), The Hyde Park Art Center, IL (‘11), Colorado State, Pueblo, CO (‘10), The National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution, DC (‘10), Bowery Gallery, NY (‘08), Mary and Leigh Block Museum, IL (‘06), and Fort Wayne Museum, IN (‘06). David was awarded a Nebraska Arts Council Merit Award and the Lincoln Mayor’s Kimmel Foundation Award in 2016. David is currently an Associate Professor of Art, Elder Gallery Director and Chair of the Art Department at Nebraska Wesleyan University.

Exeter Gallery is committed to the notion that a gallery is a meeting place for ideas and discourse. Please join us at the opening reception or email [email protected] to make an appointment to view this exhibition. Gallery open by appointment only.

May 8th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Good bad news: Gibson is filing for bankruptcy, but apparently Les Paul will survive.

May 3rd, 2018 by dave dorsey

Joan Mitchell’s Wood, Wind, No Tuba. 2 panels 9’2 1/4″ x 13 1 1/8″. At MOMA.

April 21st, 2018 by dave dorsey

Taffy #1, oil on linen, 46″ x 46″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 20th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Teal Bowl with Popcorn Popper, oil on linen, 18” x 26″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 18th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Summer Twilight, oil on linen, 12″ x 16″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 17th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Alyssa Monks from her Instagram

“White is by far the most important color. It’s what oil painting is about.” —John Currin

How is it the soap is what’s sexy? Like the indulgent curls and folds of icing on a cake or cornices of snow or seafoam and cream. All that white with incisions of hair like Gorky’s linear arabesques. Drawing with hair, the joy of the little serpentine whiplashes straightening into dark where they almost disappear, and that eye peering out like a mermaid’s cresting through the roof of her salty home to take a curious peek at the guy sans raft, going under, just before he’s gone.

April 16th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Sugar Bowl #2, oil on linen 10″ x 16″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 14th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Spiral Bowl with Flat Screen, oil on linen, 16” x 24”

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

From the sixth episode of

From the sixth episode of