Archive for the 'Uncategorized' Category

March 16th, 2013 by dave dorsey

State of Mind, Amalia Piccinini

The Painting Center has a show of paintings that explore darkness in varying degrees, still up until later this month. This one stood out for reasons that aren’t suggested in the press release from the gallery. When I saw it I thought of the twilight and night scenes of Tonalism. This reproduction is pretty good, though the painting is actually darker than this and you have to study it a while to see the subtle variations in color.

March 15th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Works at the undergrad level as well.

Works at the undergrad level as well.

March 14th, 2013 by dave dorsey

“I could do whatever the fuck I wanted to do and make a livin’.” Trailer for Sign Painters. From the blurb on Vimeo:

It’s the first anecdotal history of the craft, features the stories of more than two dozen sign painters working in cities throughout the United States. The documentary and book profiles sign painters young and old, from the new vanguard working solo to collaborative shops such as San Francisco’s New Bohemia Signs and New York’s Colossal Media’s Sky High Murals.

The book published by Princeton Architectural Press in November 2012 features a foreword by legendary artist (and former sign painter) Ed Ruscha. We encourage you to pick up a copy at your local book shop, or directly from Princeton Architectural Press –goo.gl/aTZLq

“Just to feel that, that brush. Just a little bit of drag in the paint. You could make the brush do anything you wanted to. That’s power. It’s real power.”

That’s exactly it: “Just a little bit of drag in the paint.”

March 13th, 2013 by dave dorsey

America, Will Ryman

As conceptual art, this works without any need for commentary. One glance and you get the point it’s making, and it does it powerfully and with genuine beauty. It also makes you wonder what it would be like to live inside of it. I’m pretty sure it would feel . . . what’s the word I’m looking for . . . unaffordable. America, by Will Ryman, at Kasmin, could pretty much pass for an actual log cabin, such as the one Lincoln grew up in, except that it’s seriously shiny. This little starter home would have offered Thoreau more than enough space to crash for a couple years. Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett also come to mind. But then, inevitably, one thinks, hey, nice penny jar for Donald Trump. Get up close and you can see all the consumer product parts used as building materials: car parts, railroad components, keyboard keys, corn, coal, cotton, chains, shackles, (cotton, chains, shackles . . . oh, I get it), wood, exterior paint and bullets. Bullets? Just another consumer item at Wal-Mart. (Point taken.) Any serious shopper whipping out the checkbook at Kasmin, though, must wonder, do I have to wait two years to resell it at auction or should I just, you know, melt it down now? Reminder: it’s only gold resin. Also, it’s real estate, so you take your chances. Just wondering, America wants to be an act of dissent about the decline of American culture, as seems to be the case, shouldn’t all the money from the sale go directly to Occupy?

March 10th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Apples, detail, Charles Kaiman, Oil on Canvas

Yet another painter influenced by Edwin Dickinson. (Will it never end? Hope not.) Some excellent work by Charles Kaiman at Blue Mountain Gallery until later this month.

March 9th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Guemene sur Scorff, Neil Riley

It seems to be the case, in some quarters, that you aren’t an artist until you quit making art and get to curating, which is fine with me, if it gets Matt Klos into the game. He sent me an invite to a show he’s curated that opened today at 39th Street Gallery in Brentwood, Maryland, which looks like a must-see for anyone who can get to it.

The exhibition Real and Remembrance presents paintings that have been created by direct visual experience and a construction of the “whole” through imagination and memory.” –Matt Klos

Works by:

Victoria Barnes, Dave Campbell, Tim Conte, David Jewell, Matt Klos, Aaron Lubric, Scott Noel, Andrew Patterson-Tutschka, Carolyn Pyfrom, Erin Raedeke, Brian Rego, Neil Riley, Peter VanDyck, Tom Walton, with guests

Mark Karnes and

Charles Ritchie.

March 7th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Stricken City, Paul Klee, gypsum and oil on canvas

That was the word that came to mind when I saw this in the current small exhibit of late Paul Klee at the Metropolitan on Saturday. Knowing Klee, without glancing at the title, it might have been his poetic heiroglyph for smoggy rain. But instead it srikes me as Guernica writ small. Let this be a warning to you if you’re an American suspected of terrorism, eh? You never know what arrow might strike from the skies. Klee did this one in the last years of his life, along with all the rest in the show. If you click to the Metropolitan page for this work, amazingly, you can enlarge the image until you actually are able to peer down clearly into the grooves of the surface. His lines are all incised into the gypsum. He never stopped experimenting. You can walk up and see this one right after you come out of the Matisse show, which is phenomenal and offered me new ways to see at least a dozen of that master’s works. More on that later.

March 6th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Angel faces (detail) from Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels

I managed to get to The Frick on Saturday to see the Piero della Francesca exhibit, and this one show, alone, made the long drive down to NYC and back worthwhile. I’d done a quick tour of a few galleries in Chelsea on Friday and was feeling a little dispirited. There was plenty of fine work, but nothing that I would have regretted missing, if I’d decided to blow it off and see Lebron at Madison Square Garden, or just stayed home. Ironically, I had to get to the museums for the sense that I was seeing something with fresh eyes. So, here’s a tip. If you’re going to The Frick for Piero, my advice is simple: save the best for last. Look at the lesser paintings first, and then be prepared to stand silently in amazement by the contrast between the other work and the greatness of Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels. This show is all about that one painting, and it works in this room the way Vermeer’s Milkmaid worked at the Metropolitan in 2009. It’s flanked with collateral paintings, but with both shows, you’re attending essentially a one-painting exhibit. I may be the only person who sees it this way, but the contrast between the six other paintings and this masterpiece couldn’t have been more dramatic for me. As I looked at the fragments of the altarpiece, the individual figures, I had to suppress the urge to ask for my admission fee back: after a minute or so I wanted to move on. My response was to wonder why American collectors took such pains to secure work by this founder of Renaissance painting. (Historical note: they bought them for only hundreds of thousands of dollars.) When I got to Virgin and Child, though, it was as if I were meeting a completely different painter. I had the rare sensation of looking at a quality of work I’d never seen before, which is nearly impossible to experience after decades of viewing thousands of paintings. I don’t know if this painting could change your life, as Peter Schjeldahl suggests, but I can attest that it ought to change what you think it’s possible to do in paint. Or maybe I should say it will MORE

March 5th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Proserpina, Sarah F. Burns

March 3rd, 2013 by dave dorsey

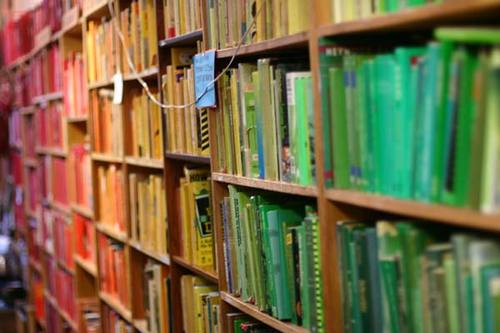

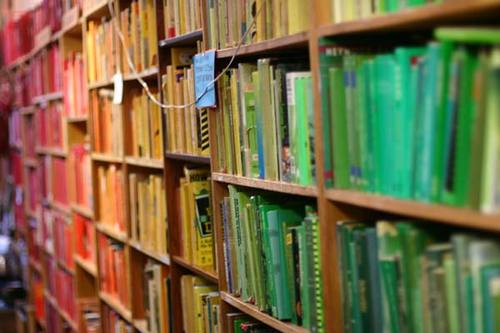

Chris Cobb’s installation

Now this is almost subversive. Chris Cobb organized all the content of this book shop, Adobe Books, by color. So long, alphabet. I think Cobb’s left brain just put his right brain on the watch list. I love the title of this installation: There’s Nothing Wrong in This Whole Wide World. If I owned a book shop, this is exactly how I would choose to go out of business. Or else I’d have the only bookstore in the world with a sign in the door: for browsers only. Why do my own bookshelves not look like this? All of mine are some earth tone or one of various shades of gray. (No, that book is not among them.)

March 2nd, 2013 by dave dorsey

Piero della Francesca | Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels (1480-1482)

Williamstown, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

Information wants to be free, as they say, but not all that free. That’s a credo and caveat for anyone who borrows content on the Internet and establishes attribution with a link. Outright plagiarism, though, is another thing, isn’t it? On the other hand, The Wasteland contained large appropriations of words which were a few centuries overdue from the library. Eliot once said, Good writers borrow; great writers steal outright. But he was an honest thief, and his footnotes were as funny and interesting and cool as the poem itself. Five centuries ago, Piero della Francesca left quite a bit of work unfinished and unsigned at his death, which meant, according to Vasari, that the parasitic Fra Luca del Borgo finished and claimed it as his own, as if he were Salieri trying to exact some glory, long in arrears, from Mozart. In Vasari’s book, Luca steals credit for Piero’s work and in the words of Vasari, he acted like those who “cover their own ass’s hide with the noble skin of a lion.” (OK, full stop. Have I actually stumbled onto the derivation of this phrase? Did “covering your ass” become public, as it were, with Vasari? If so, I hereby bequeath my accidental discovery to the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary. I’m not about to pay the annual subscription of hundreds of dollars just to see if they trace the phrase back to Vasari or thereabouts, but knock yourselves out guys.) So apparently poor Piero suffered by losing authorship of his own original work. Let’s put Richard Prince aside and imagine, in our own time, a mere work-for-hire craftsman who actually puts his own brand on a Koons or Hirst who, after the untimely death of said artists, “finished” the work and claimed it as his own. MORE

February 28th, 2013 by dave dorsey

New York Times carried a story about the renovation of intricately detailed Tibetan murals in Nepal. Looking at the photograph of the work in progress, I perked up. What I saw seemed like something from another age. Anonymous, selfless workers doing what the original artists had done, recreating an image that embodied an entire system of peaceful, life-affirming values, as well as a moral code to make those values a template for daily behavior. It was an image meant to have meaning for centuries, or, actually, for any time and place—no one who painted the image then, and no one recreating it now, suspected that the Buddhist truths behind it could be superseded by something new. None of them, for example, suspected that we would some day discover that we aren’t mortal (sorry Ray Kurzweil), life isn’t painful, or that there’s no reason to overcome our own worst tendencies. The work is meant to be a visualization of eternal verities, not temporal realities, or, worst of all, historical concerns.

When the Metropolitan announced a whole new wing devoted to Islamic art, I had the same feeling of kinship, not so much because it’s spiritual art but because of the physical demands of the actual craftsmanship. In both cases, the artwork is enormously time-consuming, requiring great patience and concentration. It’s form embodies the immersive experience of making it: the outcome is intricate, symmetrical, rooted in pattern, a kind of mandala—a symbolic representation of wholeness. Completion, balance, symmetry, order are qualities of mind for someone creating the work, and formal qualities in the work itself. The art requires selfless submersion in the effort, rather than an assertion of the self through some kind of expression of individuality. It’s almost taken for granted in this age that art is meant to be a form of self-expression, but my experience of it has been that it’s a long training in obedience to the demands of the work: and you don’t invent the demands. When I paint, it’s more about facing what I can’t do than whatever skills I’ve accumulated. The demands are imposed on you by a variety of factors: talent, the kind of art you’re chosen to make, and so on. Getting it right means struggling to discover what needs to be done, not expressing something you already know or just doing something you know how to do.

Which may explain my warm response to all this seemingly tedious work. Undoubtedly, it comes from having spent long hours, days, or weeks, attentively recreating the complex, colorful symmetries of a Persian carpet—my little personal taste of Islamic art—in some of my larger still lifes. I’ve always understood these rugs as big, user-friendly mandalas you can sink your toes into—a hint of the incredible complexity of the world, as well as the order within that complexity, the suggestion of the recursive, fractal patterns embodied in nature. Basically, you’re standing on a symbol of the universe, when you walk into a room with one of them spread out underfoot, and reproducing their patterns affords some of the same meditative calm and clarity that Islamic and Buddhist art offer to the workers who create it and MORE

February 27th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Phillip Lopate. Photograph by Jill Krementz

When I went to college, I was surrounded by people who were interested in William Burroughs, John Ashbery, Beckett and post-Beckett. The whole sensibility was, “Beckett has done this, now how can we advance his heroic move?” I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll read Henry Fielding.” If I need to experience avant‑garde, I’ll read Don Quixote or Tristram Shandy. –Philip Lopate in Harper’s

February 26th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Trailer for a documentary about Vivian Maier. I’m eager to see this and to see more of her work. Like Winogrand, she became primarily someone who lives to see, and didn’t have time to organize or track the trail of photographs that resulted from it. Paying attention became an end in itself.

February 25th, 2013 by dave dorsey

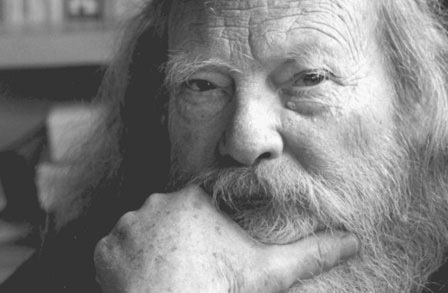

Usually, when I paint successfully, I am working from a kind of craving, not out of a compulsion to get work done. I don’t mean a vague desire to have a finished painting to hang somewhere. (That’s closer to having a goal to achieve.) I actually mean the physical feeling of desire to spread paint on canvas, so that the act of applying the paint is a gratifyingly sensuous experience. I attended a poetry workshop run by Hayden Carruth at the University of Rochester once, when Carruth was teaching at Syracuse, and he said that writing poetry was physically pleasurable in a way he didn’t understand or try to explain. I’ve forgotten everything else he talked about, of course.

Usually, when I paint successfully, I am working from a kind of craving, not out of a compulsion to get work done. I don’t mean a vague desire to have a finished painting to hang somewhere. (That’s closer to having a goal to achieve.) I actually mean the physical feeling of desire to spread paint on canvas, so that the act of applying the paint is a gratifyingly sensuous experience. I attended a poetry workshop run by Hayden Carruth at the University of Rochester once, when Carruth was teaching at Syracuse, and he said that writing poetry was physically pleasurable in a way he didn’t understand or try to explain. I’ve forgotten everything else he talked about, of course.

This isn’t true usually throughout the entire course of a single painting. There are patches and passages that frustrate me and seem to resist, but creating the image has to be delightful at some level for the image to convey any kind of delight to the viewer. It’s as if I can feel the image in my body as I’m making it real outside my body. And when I’m painting well, it’s as if I’m satisfying a physical appetite, not simply basking in a nice, warm emotion that things are going well, which is how I feel in many different situations, such as making good time on the highway, without getting stopped for speeding, while driving down to New York City. The act of driving itself is servitude and tedium: the notion that I’ll be spending less time doing it is what gives me a little glow of modest pleasure. Making a picture and watching its contours and colors emerge from behind my brush—it’s feels good in a purely physical way.

February 24th, 2013 by dave dorsey

“Being stuck in one place and bored out of your mind is the key to creativity.”

–Aimee Mann to Marc Maron

February 22nd, 2013 by dave dorsey

Big up to the paintings and the post at Hyperallergic. It’s on my list for a gallery/museum tour in a week or so. “Poons carries the torch, heralds the song, then asks us to abandon all knowledge as we stand in rapture. Empty.” Abandon all knowledge, ye who enter here. Yes indeed, as an approach to painting in general, not just Poons.

February 22nd, 2013 by dave dorsey

Rick in his kitchen

My friend Rick Harrington,just went through cancer surgery. They caught all of it, as they say, but the recovery laid him up for a couple months. Two months without painting and the mind begins to circle around how Quixotic the whole enterprise can feel. But he’s ready to gear up again and was in good spirits when I finally drove out to see his studio in East Avon, south of Rochester. He rents a house and studio next to a large expanse of farmland, which looked ready for a crop already, plowed and dark with snowmelt beyond the converted garage where he paints. (The temperature is back to 15 degrees today, so that melt meant nothing.) We had tea in his house and talked for nearly an hour and then spent another hour in his big studio, talking about painting. One thing we agreed on: this economy isn’t good for anyone, least of all artists. He had a couple years where he was selling work so fast, he could hardly keep up with the demand, and then came the real estate crash, the recession and this so-called recovery, which is mostly about Wall Street. His paintings still sell, but he doesn’t think he can map a path toward economic self-sufficiency as easily as he could have only a few years ago. The dream of forgetting about money and thinking only about how to do better creative work: how many artists can live that way? A lot fewer than were doing it before 2008.

Rick has a dog, Ulysses, who is closer to a Shetland pony than anything actually canine. He’s also more mastiff than Rottweiler (a cross between both) who was always at our sides, looking for affection, hugs, and stray crumbs of the chocolate chip cookies Rick had just baked for his two sisters who were also recovering from health issues. We talked about money, MORE

February 21st, 2013 by dave dorsey

Home Before Dark, Matthew Cornell

February 20th, 2013 by dave dorsey

My Bloody Valentine, after two decades, finally released another album. I’m thinking, what’s the rush? I still haven’t exhausted Loveless, from 1991. There’s no point in repeating the legends about this album and how it was recorded over two years. It seems tailor-made for elitist hipsters, since it makes every effort to take the edge off the music’s beauty. It has to be one of the most manicured recordings in history engineered to sound as close as you can get to the effect you get when you’re hearing three radio stations at once near some Bermuda Triangle of the dial. For me, this is Ireland’s lyrical, melodious answer to Sonic Youth’s raw power, but more ethereal and yearning and, well, innocently hopeful. The trick is to zero in on the harmonies and melodies behind the disguise of distortion. It seems you’re hearing most of it, muffled and remote, from six or seven floors above your garden apartment. So you end up playing these tracks over and over, trying to clearly discern these songs you’ll never being able to quite pin down because . . . well, let’s try again . . . because they’re being played about a mile away, and they’ve been carried to you by the shifting wind. If only you could be right there where it’s happening, hearing it the way it really is! From only a quarter mile away, say. And that’s what keeps you coming back.

Like so much of life, it’s almost there, right in front of you . . . and yet . . . and yet . . . . Turn Loveless way down, lower than you play anything else in your collection. It still sounds incredibly loud, just farther away, at a lower volume. Listen with earbuds and the difference is even more distinct. What’s noise equalizes with the actual music and you still can’t understand a single word of the lyrics but the fuzz begins to sound like the innate sound of an electric guitar and the track relaxes and everything falls into place and an actual song, arranged with haunting complexity, floats up out of the auditory bed of white noise. And yet . . . the perfect experience of hearing it is still just slightly out of reach . . .