Archive for the 'Uncategorized' Category

August 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

And yet the central issue for us is probably the question of whether the mystery at the heart of poetry (and of art in general) can be kept safe against the assaults of an omnipresent talkative and soulless journalism and an equally omnipresent popular science—or pseudo-science. It also has a lot to do with the weighing of the advantages and vices of mass culture, with the influence of mass media, and with a difficult search for genuine expression inside the commercial framework that has replaced older, less vulgar traditions and institutions in our societies. In this respect, it’s true, poets have less to fear than their friends the painters, especially the successful ones, who, because of the absurd prices their works can now command, will never see their canvases in the houses of their fellow artists, in the apartments of people like themselves, only in vaults belonging to oil or television moguls who don’t even have time to look at them. Still, the stakes of the debate and its seriousness are not very different and not less important than a hundred years ago.

—Adam Zagajewski, on Rainer Maria Rilke’s poetry, from Paideia

August 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

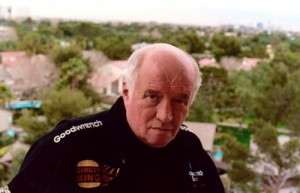

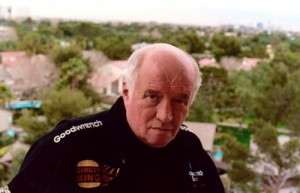

Dave Hickey

You cling to your favorite songs and books and paintings the way you once clung to your mother’s hand—because they help you become who you are and make you feel at home. Sometimes, when you see the beauty of a created thing, you recognize yourself in it and want to join ranks with anyone else who loves it the way you do. Last summer, I embarked on a 16-hour journey from Rochester through JFK and LAX to New Mexico—in retrospect, I might have been more comfortable going by wagon train—in order to join ranks, if only for an hour or two, with someone whose books have made me feel a little more at home in the world. Dave Hickey, one of America’s smartest art theorists, was scheduled to have a conversation with his friend, Ed Ruscha, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Tamarind Institute, and I showed up to listen.

Dressed all in black, with a venti-sized Starbucks coffee in hand, he was more physically imposing than I’d expected, bringing to mind Orson Welles or Harold Bloom, not only in the impression he made just sitting there, but also in the sense of his pre-eminence in his field. Balding, with a tonsured ring of dangling hair around the back of his head, he spoke in a quiet voice full of Texas, sounding like Slim Pickens trying not to be heard in the next room. While he and Ruscha traded jokes and memories, and speculated about art, I could hear behind Hickey’s comments echoes of his thinking in The Invisible Dragon, where he deconstructs the history of Western art in order to argue that beauty isn’t meretricious ornament but art’s lingua franca.

Art, he claims, is essential to the way we find order and belonging in the diversity and chaos of an open society. You buy a good drawing or lithograph and let it reorder a certain space in your house and your mind in exactly the way you vote for political leaders and give them permission to set boundaries for your life. More

August 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Thiebaud's world

I was watching a documentary not too long ago about a little pre-schooler, Marla Olmstead, who ostensibly paints beautifully composed abstracts. They are vivid, mostly cheerful celebrations of paint, and some of them are actually impressive. Unquestionably, though, they look as if someone much older had finished them. Dutifully, the documentary raises the question of whether her father has helped her paint them, or maybe is simply painting them himself—in my view they would be fine works of art even if Mr. Olmstead had been able to paint them only by pretending to be his little daughter. Now that would have been a more interesting, and certainly much funnier, investigation. But what struck me was how the director of My Kid Could Paint framed the story of Marla’s sudden emergence on the scene: as the triumph of innocent, playful joy in a jaded, postmodern art world with deadly serious pretensions of speaking truth to power, celebrating the abnormal, casting a cold eye on consumer culture, trying strenuously to be obscure and difficult, and in general doing what the French applaud as epater le bourgoisie—more or less giving the finger to the middle class, the average guy, the uninitiated. The art of cruelty, as it were.

I’ve always distrusted any view of art that assumes you need to know the secret handshake in order to really appreciate what’s going on. Matthew Barney is a genius of some kind, no question. His films are powerful and hypnotic. But I don’t have a clue what he’s doing, and I’m guessing most people who wandered with me through his Guggenheim show felt the same way. The movie about little Marla got me thinking about Matisse and his desire to paint pictures that would sooth the viewer, like an easy chair at the end of the day. Who would claim to have that goal, as an artist, now? But isn’t the art we love the art that matters most? Wasn’t that what Van Gogh and the Impressionists and the post-Impressionists were doing: painting images they believed viewers would love? Chagall, Klee, Janet Fish, Fairfield Porter, and many other painters were playing in that same space, not trying to shock anyone with their work, but to get people to look eagerly at the world, or at least at their paintings of it, with some measure of joy. And, in the process, maybe open a few minds, soften a few spirits, here and there.

Wayne Thiebaud comes to mind, doesn’t he? His landscapes construct an imaginative world with its own set of rules and laws: an alternate universe, a heightened version of the view you get from the window of a jet rising into the sky. They are visionary masterpieces, a kind of wish fulfillment, the work of a man painting exactly what he most wants to see. More

August 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Woodward's dream

Matt Woodward, an emerging Chicago artist, does graphite-on-paper drawings that thrive in the rich Middle Way between abstraction and representation, past and present, large and small, classicism and expressionism—pick almost any pairing of opposites and Woodward merges them with great originality. His method, so far, is obsessively invariant: he wanders a city, captures an overlooked architectural detail from an earlier decade–well, century–back when ornament and pattern were considered essential to our living space. He hunts for a finial, a fleur de lis, some overlooked niche of architecture—and then he creates a meticulous representation of these shapes through techniques that imbue the image with an evocative ambiguity. He sands and punishes huge sheets of paper, creating a surface full of unpredictable characteristics—which he sometimes assembles, like a puzzle, as Burchfield used to do—into panels large enough to use, in a pinch, as drywall for a large bedroom. Then he coats them with graphite dust, and finally, he draws by erasing the shapes he wants to show. It’s a brilliant inversion that goes to the heart of how time itself works: erasing what it is you want to see. What he achieves can evoke a slightly Faulknerian longing for ancient values, a world of allegiance to something more chivalrous than our media-drugged days, and yet the work has an immediacy, precision and freshness that feels entirely new. The vitality of his drawings derive from this paradoxical tension between extremes. The details are assiduously evoked, to the point where they actually shine, and yet you can’t quite pin down what it is you’re seeing—and so your mind shuttles desperately from one tentative sense of closure to another, not quite settling on a secure way to make sense of what he’s showing. He makes you dream, involuntarily, as part of this struggle to recognize what it is you’re on the way to seeing.

When I saw one of his wall-size triptychs two years ago in Rochester, NY, the effect was what Gaston Bachelard celebrated as the “oneiric” effect of certain spaces, which he equated with the half-conscious reverie induced by poetry. What had been a small cluster of grapes carved into the stone of an historic structure, though the alchemy of Woodward’s techniques, seemed to become a dreamscape, a circle out of Dante or a scene from Edgar Rice Burroughs. It was as much a vision of a physical world as an objective correlative for indeterminate psychological and emotional states. Woodward told me recently that he’d finished the work during a time of mourning over the death of his father—and his abiding preoccupation with the passage of time, had become, with his father’s death, agonizingly central to his emotional life. Art itself began as a desperate bid to hang onto something one loves, to steal it from time and save it through concentrated attention and representation, and Woodward work taps these motives. His work’s beauty is inseparable from a melody of grief that makes it come alive.

July 31st, 2011 by dave dorsey

Over the past week, I’ve heard two different people recall experiences involving psychedelic drugs in high school and college. At a wedding last night, I met a woman in her 50s, who recalled driving to Antioch College to see a film—she was attending school in Dayton at the time—and she described how the entire audience of undergraduates was high on one controlled substance or another, all of them doing sound effects to accompany a Buster Keaton flick, laughing hysterically, as if they were at a midnight showing of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. She found the whole experience funny but a little annoying. Afterward, she said, she and her friends went to a dorm room where several people who had dropped LSD were gazing with rapt wonder at a lava lamp. “I just thought, how moronic these people were.” A week ago, on a trip to see some of my own childhood friends in Boise, Idaho, I listened to one of them describe his experimentation with mescaline many years ago: “You were still yourself. It didn’t make you feel out of control, the way acid would, but it changed everything visually. Walking along the sidewalk, the ground would seem to roll up toward you and unroll behind you. Your sense of space was totally different. I remember getting into a Volkswagen van and looking around and thinking, it’s as big as a stadium. It was amazing.”

Both of those accounts confirm observations that Aldous Huxley made decades ago when he participated in an experiment testing the effects of mescaline. It might just make you look pretty childish to an onlooker, and yet for the participant, it seems to unveil an incredible depth of meaning in the most commonplace things. As William Blake put it: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear . . . as it is, infinite.” A researcher had come to Los Angeles where Huxley lived and asked if he wanted to take the drug and then report on what he saw and heard and felt, minute by minute, as the researcher recorded his commentary. Afterward, Huxley wrote a short book, called The Doors of Perception, recounting the episode in great detail, and it remains for me one of the finest books ever written about why painting matters. In fact, a fair number of pages in the book are devoted to how the drug enabled Huxley to see painting itself from a completely new perspective—how there’s a sense of significance and meaning and deep satisfaction in the simple act of perception, especially the act of looking at a commonplace object, and only after he’d taken mescaline did this become obvious to him. This book has become something like a sacred text for me, as a painter, and it serves as a little manifesto for why anyone should want to pick up a paint brush:

The great change was in the realm of objective fact. What had happened to my subjective universe was relatively unimportant. An hour and a half (after he took the drug) I was looking intently at a small glass vase. The vase contained three flowers . . . but I was not looking now at an unusual flower arrangement. I was seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of the creation—the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence. . . . Plato . . .could never, poor fellow, have seen a bunch of flowers shining with their own inner light and all but quivering under the pressure of the significance with which they were charged; could never have perceived that what rose and iris and carnation so intensely signified was nothing more, and nothing else, than what they were . . .

I’m not sure that’s dig against Plato is justified, but when I read this, it occurred to me that he’s saying nearly everything Martin Heidegger ever wanted to say—his ontology reduced to clear, no-nonsense conversational prose—about how our evolution and civilization have obscured the simple, fundamental apprehension of Being. More

July 25th, 2011 by dave dorsey

C.S. Lewis

My friend Sancho sent me a great quote yesterday, which, for me, captures the nature of originality. Recently, I told James Hall, the owner of the Oxford Gallery here, that Van Gogh’s unique style was the result of everything he couldn’t do as a painter, in a technical sense, and he laughed. But it’s true. Originality doesn’t require any effort other than the intense concentration needed to get something right, without any thought given to being different or new or fresh and all the quirks of how you are able, and unable, to paint emerge in that effort, on their own. Your own individuality, especially your limitations, will give the work an original feel, on its own:

. . . in literature and art, no man who bothers about originality will ever be original: whereas if you simply tell the truth (without caring twopence how often it has been told before) you will, nine times out of ten, become original without ever having noticed it.

C.S. Lewis

July 20th, 2011 by dave dorsey

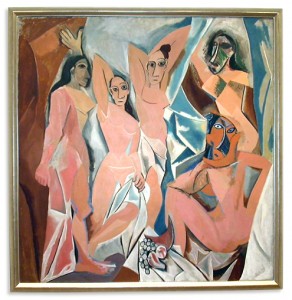

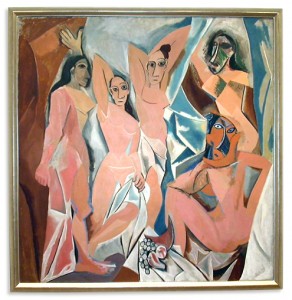

Picasso's "French whores"

Last year, at a symposium held by the Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque, I met Dave Hickey. Well, let’s be more precise. I went up to his table and asked him to sign my copy of The Invisible Dragon and said some words of sincere flattery and then left him to his conversation with Ed Ruscha. Yes, I was one of those annoying people who do that. I’d listened to the two of them discuss Ruscha’s work before a packed auditorium earlier in the day, during which Hickey had made a crucial assertion: it isn’t necessary to understand Ruscha’s work, but simply to love it so much you want to see more of it. This is, in a way, the heart of Hickey’s views on art: it’s about beauty, not meaning. (That’s a gross simplification that leaves Hickey’s indebtedness to Foucault out of the picture, but it will have to do.)

Hickey’s views on what has happened to Western art over the past several hundred years are both brilliant and troublesome. The people who love Hickey, as I do, are those who would have nothing to lose in the event that the entire structure of the art world were to be overthrown and replaced by a more democratic market economy in which the worth of art is determined by the love it evokes among those who look at it . . . wait a minute, doesn’t that describe the system that has elevated the likes of Koons and Hirst to their status as art world plutocrats? Hickey probably has no problem with that, though many do. For Hickey, the sale of art is the whole point of making it, and there’s nothing meretricious in that attitude, it’s simply the working out of his views about democracy, self-determination, freedom, and the wisdom of crowds. Here’s how he characterizes the birth of cubism in his book: More

July 18th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Henry Whysall

In May, I attended the Persona Art Festival in London. It was organized by two young curators, Antria Pelekanou and Zia Fernandez, who assembled a challenging show of emerging artists from around the world–the UK, the United States, China, Germany, Slovakia, and many other countries. It was energizing to spend a few days with people passionately devoted to visual art, which ranged from film to performance art to painting, drawing and even a spooky, fascinating peephole diorama.

It was held in The Rag Factory, off Brick Lane, and on Saturday afternoon, a few of us headed a few doors down to The Pride of Spitalfields, one of London’s oldest continuously operating pubs—a real one, not an afterhours hangout for the financial district, a few blocks away. In attendance, standing on the brick pavement outside, a tall, patrician, adept 34-year-old conversationalist, Henry Whysall, kept squaring off against a 25-year-old Slovakian, Lenka Brazinova,

Lenka Brazinova

a largely self-taught painter just getting started, visiting from her home in Kosice. He wore a collarless, horizontally striped shirt and Lenka wore what looked like a sewn-together kindergarten puzzle: red sleeve, yellow sleeve, blue hood, along with a pair of bright red, old-school Adidas Gazelles. Her Slovakian accent, Russian-sounding, was heavy, but her English was quite good and she missed nothing in the conversation, her eyes bright and animated. A mentor once nicknamed her Little Black Puma. Rage Against the Machine is her favorite band. In the festival, her oil is a boldly Fauvist pair of nudes on a beach, a hedonistic glimpse of a pleasurable moment of idleness. Whysall’s work is an abstract grid of 67 small rectangles of handmade paper, lumpy and tactile, impregnated with wax and tainted with chemicals that imbue beautiful, otherworldly colors into the support—each small square of paper in its own frame, behind glass, like an artifact or collectible, full of colors that don’t seem possible to achieve with any other medium. They’re luminescent and magical and the work has a tactile presence that reminded me of Braque’s great mid-career paintings.

mid-career paintings.

“Money, no. It’s not the reason for painting, you can’t paint for money,” she said.

“I think the way art is valued and sold, and the way it’s produced now, perfectly reflects capitalist society. I’m not sure there’s anything wrong with art that reflects the system that supports it,” Whysall countered.

“But you do it for money, it’s worthless. You lose the meaning,” she snapped.

“Isn’t art supposed to represent the world you live in? Right? If that world is driven by money then the way art is produced can reflect that.”

There’s a bit of cat-and-mouse sophistry here, on Henry’s side, but he’s enjoying the way she won’t let up, and he’s loving her intensity.

“Do you like Mike Leigh?” I ask. “The early films?”

“Some. I’m ambivalent about him,” he says.

“Exactly. When it just seems you’ve turned on a camera and you’re recording the way the world is, is it art? The early Leigh, I mean. I’ve never been sure that kitchen sink realism is really art.”

“You’re saying art does more than just mirror the world. ”

More

July 15th, 2011 by dave dorsey

The World of Van Gogh

When I was in my teens, my parents subscribed to a series of middlebrow art books, published by Time-Life, each one devoted to a different artist. I still have all of them, nearly thirty volumes, from Giotto to Marcel Duchamp. The one that made me a painter when it arrived, was The World of Van Gogh. I remember the rich scent of ink and glue of these monographs as they emerged from their slipcases for the first time. From the story of Van Gogh’s life, it was clear he had all the requisite characteristics for artistic beatitude—eccentric, mentally unstable, poor, volatile, brutally honest, hungry, drunken, suicidal—a persona that now, the way art has become a professional career with its own paths to money and notoriety for the lucky elite, seem a tired and worn-out cliche. We’ve outgrown all that misbehavior haven’t we? We’re professionals. Hasn’t the art world become too postmodern and money-crazed to believe in Van Gogh’s sincerity, his dysfunctional devotion to a truth that would be seen as economically and culturally determined? Skimming through the text of this book again, after all these years, I realize that Van Gogh’s life and work remains for me, at least, part of the paradigm of why art matters. He never stopped addressing common people in his work with images that speak to everyone in a universal way.

I find this passage:

He seemed to have developed “almost mystical ideas about color that are reflected in his late art. He sensed that color has meaning that transcends mere visual impression. Yellow, red, blue—indeed any color—can connote something that lies beyond the reach of rationality. . . . (and) before he left Holland, he went so far as to relate colors and music—and even took a few piano lessons. ‘Prussian blue!’ or ‘Chrome yellow!’ he would cry as he struck a chord.”

I keep reading, turning pages, still looking for the paragraph I know is here somewhere. I find yet another:

It was the brilliant color and clear outline of the (Japanese) prints that most strongly caught his eye as he emerged from the dark tonalities of his Dutch period. But his constant regard for the social function of art was involved too. The prints, even after the cost of transporting them halfway around the earth, could still be sold in Paris for only one or two francs and thus were within the reach of people to whom he addressed his own work. ‘I do my best to paint in such a way that my work will show up to advantage in a kitchen,’ he wrote, ‘and then I may happen to discover that it shows up well in a parlor too, but this is something I never bother my head about.’ He had long since sketched out an idea for an association of artists who might, through lithography, make copies of fine works of art available to workingmen at low cost.

Not only was painting a spiritual pursuit, a meditative pursuit in search of mystical color harmonies that could bring the peace of contemplation, it was also a way of offering this gift to even the most common, uneducated people. To anyone, in other words—painting was a language that spoke to all people, with the immediacy of its music. So that it would make sense to hang the greatest art in an ordinary kitchen. More

July 14th, 2011 by dave dorsey

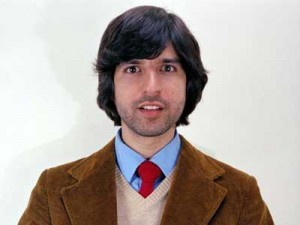

Demetri Martin, comedian and painter

A while back, maybe a couple years ago, Roberta Smith, of the New York Times, observed that visual art is becoming–or has long been–an intellectual ghetto, of sorts, comparable in its reach to the tiny span of influence enjoyed by contemporary poets and their readers. It doesn’t seem that way because so many past artists remain recognizable household names–and their work is still summoned onto the walls of major museums in blockbuster retrospectives. The recent MoMA show, Matisse: Radical Invention, was challenging and illuminating, and offered new insights into how Matisse and Picasso kept a wary, respectful eye on one another, learning, reacting, developing their work in a spirit of competitive homage. It brought to mind how The Beatles and Beach Boys played a bit of one-upmanship when they were recording. Yet a big show like this one also operates on a meta-level, reassuring painters like me that art remains something vital to large numbers of people–with a roster of big names any educated individual will recognize. There’s an illusion built into this subliminal message. The reality is that most great work being done now is completed in obscurity, with little opportunity of reaching large numbers of people, or even any people outside the small community of souls who pay serious attention to visual art. Who do we have now for Big Names? Jeff Koons? Damien Hirst? John Currin? These figures live in a bubble of luxury familiar only to elite CEOs and media celebrities, and yet what percentage of the population would be able to tell you anything about their work, or even recognize their names? Go down a few levels to the little-known people who are doing powerful, beautiful, compelling work, work of genuine quality and value, and you’ll get blank stares from the man or woman on the street–and you’ll find artists who make precious little through the sale of their work. For a painter, the sad reality is that the rewards are entirely inherent in mastering the work itself–and in the hope that, by doing so, you’ll be able to create something that helps someone else connect with what matters in his or her life.

I listen to podcasts while I paint. A lot of them. Marc Maron, Sound Opinions, Radiolab. On a recent Sound of Young America, Jesse Thorn interviewed the cerebral comedian, Demetri Martin. The conversation made some interesting connections between skateboarding and comedy, and then moved on to the subject of visual art–since Martin is a painter. More

July 11th, 2011 by dave dorsey

The Milkmaid

From the autumn of 2009 through the end of last year, I helped Peter Georgescu, a retired CEO, write a book about his extraordinary life. The job required me to fly to Manhattan at regular intervals and stay there for as long as a week at a time.

Here’s the thing. This project, which was rewarding in and of itself, also gave me enough free time to wander around Manhattan to see some impressive exhibitions. There is nowhere like New York City for an education in the visual arts—it’s astonishing what you can learn simply wandering around for a few days. I saw a selection of William Blake’s watercolors at the Morgan Library, including many he did for his version of The Book of Job. The older I get, the more I admire and marvel at Blake’s achievement, though I have almost nothing in common with his visionary aims. I love his work in a personal way partly because J.D. Salinger claimed to love it, which made me curious about the poet in college, and partly because I took a graduate seminar devoted exclusively to his poetry while at the University of Rochester. His Gnostic vision lodged itself in me in a way I’ve never been able to shake. (When I got to London earlier this year, it was a joy to see how the Tate Britain gives props to crazy eccentric Billy Blake, alongside Turner and Constable and all the rest.) On this same visit to New York, I saw a tiny El Greco at the Onassis Cultural Center, The Coronation of the Virgin, which showcased his astonishing facility with oil paint. It was a mere study, and the three faces couldn’t have measured more than an inch from chin to hairline, yet their expressions were incredibly complex and full of emotion—conveying three distinct and recognizable states of mind. We’re talking about faces the size of pocket change. The craftsmanship required to convey this profound depth of feeling through such tiny profiles doesn’t seem humanly possible. I stood in front of that image, silently, for a long, long while. El Greco’s spirituality seemed to find expression as much in the way he handled paint as in any of the religious scenarios he was using it to represent. Seeing that small painting enabled me to understand why the contemporary Chinese installation artist, Chi Guo Chiang is obsessed with El Greco. more

July 11th, 2011 by dave dorsey

There is only one thing in art that is worthwhile. It is that which cannot be explained.

–Braque

July 9th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Betty by Gerhard Richter

“One has to believe in what one is doing, one has to commit oneself inwardly, in order to do painting. Once obsessed, one ultimately carries it to the point of believing that one might change human beings through painting. But if one lacks this passionate commitment, there is nothing left to do. Then it is best to leave it alone. For basically painting is idiocy.”

–Gerhard Richter

There is so much to argue against here–this missionary sense of purpose–but Van Gogh would have agreed completely and if Vincent gives something the thumbs up, I’m down with it. The fulcrum here is the phrase “change human beings,” which makes Richter’s credo sound sensible. He doesn’t say “change the world.” It isn’t a social or political agenda he’s talking about–though politics certainly hasn’t been outside Richter’s wheelhouse. Can a painting change you by helping you wake up to who you actually are? As I typed this, a catbird landed on our birdbath here in Pittsford, New York, and I’m thinking, no one has ever made a painting as marvelous as the way this nearly invisible gray bird looks and sounds. Does that bird, by flying into my field of vision and inspiring my humble appreciation for it, just now, change me in some way? If so, I think that’s the way a painting should change someone who looks at it.

July 8th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Brueghel's Tower of Babel

Gazing at a great painting for the first time feels a lot like introducing myself to someone fascinating and a little mysterious. Actually, that’s exactly what’s going on. In a sense, I’m becoming friends with the person who created it, and a great painting conceals and reveals itself, as an object of appreciation and understanding, the way its creator would. And what you “learn” from it is analogous to what you learn by becoming friends with someone. It’s more complicated than “knowing.” If the painter has managed to subconsciously fuse his or her life into the work—in other words, insofar as it’s actually a work of art—the painting becomes a portal into who that person is. What it literally represents is beside the point. If the work’s purpose is to illustrate some conscious notion the artist holds—the sordid and oppressive nature of the male gaze, the hegemony of European culture over the Southern hemisphere, the emptiness of celebrity, what have you—it will do what it was meant to do, if it’s good. But it won’t be doing what painting is uniquely qualified to do. Once you get the message, why look twice? More

July 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

How many words does it require to support an intellectually contrived image? I own The Cremaster Cycle. It’s a cinder block of a book, full of Masonic mystification. In a way, it’s the ultimate Artist’s Statement. I haven’t read a page of it. And I haven’t looked much at the pictures either. My fondest memory of the Matthew Barney show at the Guggenheim (my most unpleasant memory is of buying this enormous book devoted to the show and then straining my lower back by lugging it up along Fifth Avenue) was spotting Isabella Rosselini on one of the upper floors, without makeup, keeping it real by looking really depressed and lost. Some things you can understand only in their context, and that look on her face was one of them. It was the look on my face too.

July 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

The money shot

Recently, I heard from my friend, Sancho Panza, in Tennessee. (I love Tennessee because it’s hilly and beautiful and because Nick Blosser paints there. But I digress.) Sancho doubts. He mocks. He finds me amusing and occasionally annoying and generally thinks I live in a world of fantasy. Sometimes, he addresses the level of truthiness in my thinking. Other times, he’s dead wrong about whatever, but when it comes to the realm of art it’s refreshing to hear from him. He’s a sort of bollocks alarm. When something looks fraudulent in a groupthinky way, as it often does, in the empire of art, he just comes right out and asks “Who cut the Moose House cheese?” He spotted this item from Popular Photography and proceeded to ask why:

Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled #96″ from 1981 has become the world’s most valuable photograph after selling for a staggering $3.89 million at a Christie’s auction yesterday (it was estimated to be worth up to $2 million). The winning bidder was Philippe Segalot, a private advisor to some of the world’s wealthiest art collectors. The photo takes the top spot away from “99 Cent II Diptychon” by Andreas Gursky, which enjoyed five years as the world’s most valuable photo after selling for $3.35 million back in 2006.

Me: Yes, the auctions are hitting new highs. The bubble continues. She’s an interesting character.

Sancho: How do you explain what the bubble chooses?

Me: She’s been around for decades. She’s “established.”

Sancho: But then they randomly settle on one piece of work? This is what strikes the outsider as nuts. More

July 6th, 2011 by dave dorsey

from the Barns collection

If I step back and just observe myself while I paint what I notice is pretty simple—and extremely simple-minded. I become less and less conscious of myself and what I want my activity to mean and far more aware of the feel of what I’m doing. When I know, with the entirely subjective certainty of someone in love, (translate: deaf and blind to the opinions of others) that everything I’m doing is exactly right, a number of conditions hold up. I’m aware of having established a set of personal rules, which I’m following at a steady, rhythmic pace, not too fast, not too slow—the quality of the brushwork, the thickness of the paint, how closely I maintain crisply defined edges and outlines, exactly what colors I will and won’t use, and what kind of sheen I expect the paint to have when I’m finished—slightly matte, not reflective, no shine at all, seemingly as soft as the cloth that supports it.

I might be the only person in the world who cares about these things, ever, but the strange thing about painting well is that these factors become all-important. I’m never focused on what the painting has to say, or what it “means,” or how “significant” it needs to be. All of these variables would appear entirely arbitrary to anyone else, but for me they become an absolute necessity. My Ten Commandments. My Noble Truths. My Rules of Order. Whatever. Once I start swerving away from those personal guidelines, and that steady Dr. Dre tempo they impose on my work, those minute particulars and private measures of excellence, there’s no going back—it’s all More

July 6th, 2011 by dave dorsey

represent

— to present an image of something through the medium of a picture

— to bring clearly before the mind

— to set forth in words; state or explain

— to have the nerve to speak for others of your group