Archive for the 'Viridian Artists' Category

March 3rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

Blinded by the Light

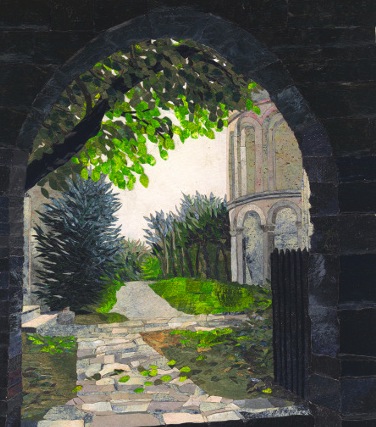

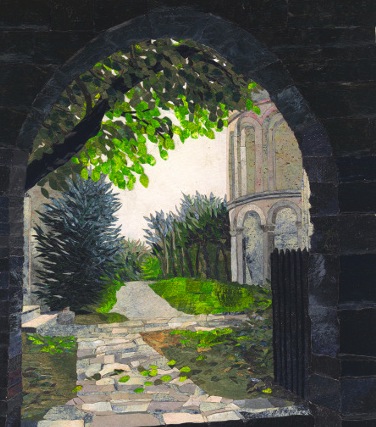

If you want to see yet another way obsession gives birth to beauty, check out the work of Mary Wells at Viridian Artists, a show that runs through March 10. After a visit to Rome, where she discovered mosaico minuto, the art of glass mosaic—images constructed of tiny colored glass filaments—she came back home to Portland, Oregon and invented a way to do it with tiny fragments of paper. The resulting work is as intricate and luminous as a magnified photograph of the scales in a butterfly’s wing. What’s most amazing is how, working from her own photography, she’s able to evoke the light of different seasons. The work depicts scenes from two locations in Italy—the Villa Vignamaggio, ostensible Tuscan birthplace of Mona Lisa, and the cortile of the Ducal Palace in Mantua.

Working from her photographs of the Villa Vignamaggio during each of the seasons, offering a visual representation of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. Her pace allows her to complete no more than a square inch per hour, so the four panoramas, begun in 2008, were completed earlier this year. Each one contains 70,000 paper tiles. The smaller mosaics in the show offer smaller views of the same villa: gardens, flora, vistas and architecture. An additional triptych combines mosaic and painting, with a scene, rendered in cut paper, framed by a painted image of a window flanked by pillars. To complete the work in this show Wells relied on three residencies over the past two years at La Machina di San Cresci in Greve in Chianti, Italy.

I sat down with Wells at Viridian today for a conversation on her work:

DD: How did you learn this technique of assembling cut paper? More

February 20th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Vernita N'Cognita, Invisible Woman

I drove to NYC Thursday to attend Vernita N’Cognita’s performance of Invisible Woman, at Viridian Artists. I’d spoken with her previously about her work, which focuses on the experience of women in contemporary life. I was especially interested in this performance because of its resonance not simply for women but also as a metaphor for Vernita’s life as a visual artist—and, by implication, the lives of most visual artists. I also felt compelled to see the actual performance, as a gesture of support, rather than watch a video of it on YouTube, because she had been hospitalized for ten days last month, with a rare blood disorder. Her treatment at New York Presbyterian involved five plasmapheresis treatments, where her blood was routed outside her body to remove and replace all of her plasma. In a conversation with a friend of mine, I heard about Vernita’s weakness—having lost ten pounds from an already waif-like frame—and her fierce determination to go ahead with her performance, regardless.

“I have a new hero,” my friend said.

N’Cognita’s work is rooted in butoh, a Japanese art form that began in the 50s when two dancers created it as a rebellion against existing traditions. It relies on exaggerated and slow physical movements, superficially similar to tai chi. More

December 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Janet Bohman, Vernita N'Cognita, May Deviney at Viridian

After helping her and a couple other fellow artists hang the new show at Viridian Artists this past weekend, I sat down with Vernita N’Cognita at a little gourmet pizza place around the corner, just off 10th Avenue. She’s been associated with the gallery for more than a decade and is now its director. I consider her the presiding spirit of compassion in that little gallery, someone who has a cool sense of humor and a warm heart. She changed her name from Vernita Nemec to Vernita N’Cognita as an homage to the “unknown artist,” which is consistent with her vocation as director of exhibit space for those who aren’t represented by more commercial galleries. As an artist, she’s built a long-standing reputation in branches of art I know much less about than painting: performance, installations, collage. She was a part of the SoHo scene in the early 70s when it was just emerging, and has been a recognized figure ever since—she’s still being invited to perform in spaces at various sites around the world, though she’s never achieved fame or earned much for her work. She comes from a Catholic family in Ohio, raised by what sounds like a pair of caring, attentive parents, her mother a housewife and her father a tradesman, and this upbringing has been the subject of some of her most interesting and lyrical performances—which are invariably about the way it feels to be a woman in contemporary America. She calls herself a feminist artist, yet when she describes her work, it sounds more subtle and literary than polemical. What I took away from our conversation was a sense, now more than ever, that an artist needs to define the nature of “success” and what it means in a personal way. In most cases, it can’t be about money, nor even about the scope of one’s audience: artistic integrity might ultimately depend on being able to make a living doing something else. And not ordering the tenderloin.

Vernita: When I started out, I lived on 11th. Then on Christopher. Now on Canal St., where I’ve lived for a thousand years. I was mostly painting and doing installations. My first gallery was SOHO20, one of the first feminist galleries. I’m still on their board of directors. Actually, I’m curating a 40-year retrospective for them. After I left SOHO 20, I showed in colleges and other alternative spaces. Then at Gallery 128 on the Lower East Side. Now, in addition to Viridian, I curate a restaurant in Queens. Restaurants make sense except for the fact that the work smells like food. (She laughs) I did a show there and I made my price list like a menu: appetizers, main course and dessert. I ran this arts organization called Artists Talk on Art, which was an historically important organization for ten years. You don’t get money for any of these things, but it broadened my reputation. People think I’m a helper for artists.

As Lauren Purje pointed out, there isn’t just one art world.

People forget that Mary Boone went to RISD and the guy who wears the bathrobe and makes films. . .

Schnabel.

Julian. She went to school with him. So of course he shows in her gallery.

You almost have to define what you mean by success.

Exactly.

Some artists don’t want a gallery to exert control over what they do. You have to figure out how to make money. How have you done it all these years? More

November 21st, 2011 by dave dorsey

Lauren

This is an email I got this morning from Lauren Purje, my friend in Brooklyn. I wrote about her a few posts back. She works at Viridian Artists and will be showing her work there in the future, and she also has a solo show in Buffalo coming up soon. We’ve been talking about collaborating on something which intrigues me because we’re making art from completely different directions: I want my painting to get as far from words and concepts as possible, and her work is steeped in both, rooted in a quizzical stance that’s essentially philosophical. She’s always thinking in the most circumspect way about how to be an artist. From this email for example: “The meaning of art changes based on the venue you market it in and the value somebody puts on it.” That’s a pretty big caveat. Matt Klos pointed out to me a while ago that Stanley Lewis stuck with his artist-owned gallery even after his work started to sell for decent money. I would guess his thinking was the same as Lauren’s. Keep it real and address those who are looking at the work itself, not what it’s going to be worth in two or three or ten years. Her path in Brooklyn and Manhattan fascinates me, and I want to keep in touch with what she’s doing, how she passes hurdles or shies away from them, always thinking less about a “career” than what she wants her art to mean. I think she hits on quite a few essential things in this email, so she said I could pass it along:

Bob Cenedella, (professor at the Art Students’ League and my original connection to NY, I consider him a mentor) likes showing in bars and restaurants more than galleries, now that he’s done it all. He’s coming from a long career where he’s dealt with the art world and many times has been censored by it. His attraction to the bar scenes I think boils down to having his work seen by everyone–art in normal situations. His work is often political, or just plain satire. He hit it big back in the day when he had shows alongside Andy Warhol, but he was selling Brillo boxes for 15 cents, 5 cents if you assemble it yourself, haha— just to say it was bullshit.

It’s sometimes confusing. I don’t want to be bitter, but I know that the gallery system is pretty fucked up. I guess I’m just looking at it in terms of, who’s really looking at your work when you’re in Chelsea compared to maybe a bar on 2nd ave. There’s a lot of grey area, between Richard Serra and any Viridian artist–there’s not one ART WORLD, but lots of little ones. The one everyone thinks of is Jenny Holzer’s and Matthew Barney’s . . . Ford snuck in there. But exhibiting in places where people eat and drink is a way of reaching more people.

More

September 30th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Susan Sills, Bather with Towel

A new group show is up at Viridian Artists, where I’ve recently become a fellow member. We’ve moved to 548 W. 28th St., in the upper region of Chelsea, from a couple blocks away. I joined the gallery this past summer, and I’ve been visiting to help out, attend meetings and generally get to know the other members—Vernita Nemec, Susan Sills, Bob Mielenhausen, and many others, including a couple promising young non-member artists who work at the gallery, Lauren Purje and Rush Wittacre. It’s a great gallery, founded when most of the prominent artist-owned galleries sprang up, in the early 70s, back when the global art world was still anchoring itself in Manhattan. In fact, feminist work by Nemec and Sills from that era was recently acquired by Rowan University, in Glassboro, New Jersey, from the collection of Sylvia Sleigh—and artists represented by the collection were honored in a ceremony to celebrate the acquisition in September.

The Viridian group show, Moving, to inaugurate the new exhibition space is a great overview of the diverse work being done by members—and, to be honest, I was surprised at how strongly I responded to the Susan Sills cutouts when they were already on display at the last group meeting. Sills does life-sized wood cutouts based on works by the Old Masters, and they not only have a wry sense of humor, their craftsmanship is remarkable—you know you aren’t standing before Las Meninas or Degas, yet her ability to evoke the look and spirit of the original is remarkable. I recently had an email discussion with some photographers about ongoing controversies over appropriation of previous work—sparked by ridiculous imputations of plagiarism surrounding Bob Dylan’s artwork, where he bases his imagery on work by earlier artists. I agreed that the mania surrounding intellectual property and plagiarism seems to ignore the centuries-old practice of reworking imagery from earlier masters: “after Delacroix” or “after Rembrandt” was commonly appended to the title of an homage, usually meaning a copy, of some previous tableau. The timing of the discussion was serendipitous since I’d been delighted by Sills’ work during a visit to the gallery a couple weeks ago. In general her cut-outs serve not just as an homage to an earlier painting, but they bring the previous image into three-dimensional space, extended it into a provisional diorama, replete with three-dimensional objects. It’s as if the little infanta in Las Meninas has popped upright from the pages of a book and assumed the dimensions of an actual child. Degas’ bather sits beside a real tea kettle. And Picasso’s mother, teaching a child to walk, leans over her child’s shoulder near a set of square cubes—a baby’s playroom building blocks, which Sills adds to the scene as an amusing way of transforming Cubism into child’s play. What struck me most, though, was the way Sills used the cutout to gently chide Picasso himself—focusing on his repressed gentleness, his fondness for his children, and making that the whole point, ignoring his default persona as the great alpha male of 20th century painting. At the same time, as she pays homage to Picasso’s work, she has picked a painting where Picasso himself was honoring an earlier artist, paying homage to a series of drawings Rembrandt did of women teaching children to stand and walk, many of them in the permanent collection at the Tate. She shows how modern art is as much about tradition as it is about radical invention. By giving these previous masterpieces a three-dimensional power, Sills makes them more inviting, more intimate, a companionable presence in a room—showing how much the work of painters long dead can continue to have a vital presence in the life and work of contemporary artists.

August 26th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Two Trucks, with Tools

Anyone who doubts that painting is mostly a physical engagement with the world should have followed me around the past three days. I drove to Chelsea, to help another painter, Rush Witacre, build a set of storage shelves at Viridian Artists on 28th St. As a member there, I donate 40 hours of labor every year—doing whatever needs doing when I can get into the city for it. When I joined Viridian, our director, Vernita N’Cognita, asked me, “Are you handy?” I should have known better than to be honest about it. Three days ago, just before I left, I stood in our kitchen and took that photograph (up above) of my cargo for the visit to Manhattan. A power drill, extra batteries, a stud finder, a level, tape measure and—oh yes—a painting for “Moved,” the show opening next month to celebrate our new space, a few blocks north of where the gallery had been located for a decade. It was a move I’d helped the gallery make in July by loading heavy objects into Rush’s four-door pickup truck and then lugging them up to the new space, in a building wedged between a Porsche/Bentley/Rolls Royce dealership on one side and, on the other, Scores, the strip club Howard Stern helped put on the map. Directly next door to our building was what appeared to be an apartment complex called Art +, with a motto painted onto the street-level window: “Chelsea, the birthplace of creative modern art and the home of bad behavior.” I’ve been a member-level supporter of both of those causes, at one time or another, so I feel at home when I’m here.

It takes about five hours to drive to Manhattan from our Rochester suburb, which almost seems like a commute to me now, I’ve done it so many times. Yet our first afternoon of work was a lesson in the relative meaning of mileage. More