August 30th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Christopher Burke, Roof Line Studios

From Columbus, Ohio artist, Christopher Burke’s, Instagram feed. I like where he’s going with the simplification of the image, and wondering what he might do with color using this kind of format with cropped images of houses. He could render these structures with any colors he likes, even if the sky remains relatively constant. The simplicity of this one is part of what gives it such impact. I had that same reaction to the potential for color at the last Hirschl & Adler show of John Moore’s latest images of the studio where he paints, which appears to be a former industrial site. There’s room for personal improvisation with color in the work of both artists, representing architectural structure in ways that echo geometric abstraction. It appears Burke will have a solo show next year at George Billis Gallery in NYC.

August 22nd, 2016 by dave dorsey

Snow Effect, Gustave Caillebotte, Musee d’Orsay

She’s got a pleasant elevation . . . she’s drifting this way and that

not touching the ground at all, and she’s

up above the yard . . . –Talking Heads

It was a delight to find a brief, astute essay from Donald Kuspit on the French painter, Gustave Caillebotte, in the current issue of American Art Quarterly. He writes about Caillebotte’s ambiguous position as a painter during the Second Empire in France. Kuspit improvises like a virtuoso on his central topic: Caillebotte’s “revolutionary” use of perspective to juxtapose indoor and outdoor space as a way of visualizing the individual’s plight during the modernization of France under the heavy-handed reign of its latest emperor. He embraced the revolutionary natural light of the Impressionists without losing a structured perspective antithetical to their work in order to create a sense of indoor intimacy even in his outdoor images. The viewer often floats slightly above his scenes, looking down, levitating just off the ground, like Icarus at the start of his escape from the maze, not quite ready to fly.

Kuspit plays with these themes and weaves them in subtle and elusive ways, but his central point is that Caillebotte was creating a vision of Paris in which the intimate and personal—the quiet calibrations of a disappearing way of life—were contending with the required conformities of a modernizing society. When outdoors, people in his paintings seem to inhabit a protective and portable zone of intimacy—it may be only as big as the shadow of an umbrella—caged by a grid of architectural uniformity stretching endlessly into the distance. It’s a polarity out of Anton Chekhov: the emerging and crass middle class, grasping its new money, encircles and infiltrates the withering aristocracy—here the new architecture of Paris serves the role of invasive captor. Yet Caillebotte was both an independently wealthy member of the haute bourgeoisie and a defender of a human scale of life confined by the economic growth. Members of his own circle usually provide the focal point of his paintings—and they are those who are profiting from that growth and change. He identifies with them, while Chekhov stays at one remove from his grasping, climbing arrivistes. Like Manet, this painter found his place on the threshold between past and future, and his work emerged from an allegiance to both.

That is what makes Caillebotte rewarding when subjected to intellectual scrutiny like Kuspit’s, the impression he gives of a divided fidelity, a delicate balance. As Kuspit summarizes it:

The emotional and spatial differences that inform Caillebotte’s paintings climax, as it were, in the much-noted difference between his handling: the “flat,” “dry,” “academic” surface and linear clarity of his indoor paintings has led some art historians to label him a conventional realist, while the “animated,” “wet,” “anti-academic” surface of his outdoor paintings have led other art historians to label him an Impressionist . . . sometimes this doubleness happened in the same picture . . .

Yet I’m uneasy with Kuspit’s thesis when he implies that Caillebotte’s use of perspective is somehow a rebellion against a tide of conformity turning Paris into a modern, alienating city. His perspective is “oddly impulsive and unpredictable . . . insulting and offensive, intruding on the bourgeois Paris of Napoleon III, just as Impressionism intruded upon academic realism, the preferred mode of the official Salon and the bourgeois patrons of art.” Kuspit is so adroit with his theme he can get you to nod through this, though I find little in these paintings that insults or offends my sense of reality. Kuspit is more persuasive when he synthesizes the dichotomies into the sense of hope that actually dwells in these paintings: all that modernization was actually making life better. The world has become oppressive in some ways, under the dictatorial reign of the Second Empire, but overall things were getting better.

There is a disjointed look to Caillebotte’s paintings—the parts don’t neatly relate. His men and women inhabit different emotional spaces, just as his closed and open spaces have a different emotional tone, as do his bright outdoor light and dimmer indoor light. They’re all implicitly estranged, yet unavoidably together in the new Paris, suggesting that they can be made new, or at least made better, as the remaking of Paris made it a better place to live.

Caillebotte’s use of perspective conveys almost a sense of weightlessness and his paintings rarely feel oppressive or critical as much as bemused and almost opportunistically clever in exploiting what’s there all around him: he sees all that impersonal architecture as a natural way to create pictorial structure. His scenes mostly bring me a sense of relief and make me feel the possibility of private freedom in a public world that is anything but liberating. But perhaps that’s Kuspit’s point. The academics would have objected to the instability of this playful use of levitated perspective which frees the viewer. This idiosyncrasy of his as a painter might have been seen as an affront—individual quirks are effectively a departure from the norm.

He writes, “I am suggesting that Caillebotte was neither an academic realist nor an anti-academic Impressionist, but a critical realist. He conflated both modes to convey the tension between conformity and nonconformity—bourgeois art and avant-garde art . . . ”

It’s ironic how, with the passage of time, the revolutionary movement of Impressionism became the ultimate “bourgeois” art, offering some of the most crowd-pleasing and popular images ever painted, anchoring lucrative tent-pole museum exhibitions for many years now. There’s a good reason for this: Impressionism is true to human experience. Impressionism conveys the way the world actually looks to the quick, moving eye—the living eye. The significance of this art for viewers now has little to do with its position in art history, but with lasting qualities of human nature. Impressionism was a discovery more than an innovation. It imitates how we actually see the world when we are busy making our way through it. And this is something that holds true both then and now, again irrespective of art history—what is most spiritually valuable in art is what transcends its historical situation. (By contrast what makes some paintings so expensive, as opposed to genuinely worthy, can be the role they play in relation to the official history of painting.) Caillebotte’s work will outlast any interest in its relation to art history, because what his best paintings convey is nearly inexpressible, and remains now precisely what it was when he painted them.

My sense is that he wasn’t consciously rankling against the formal restrictions of both academic painting and the new impersonal world rising up around him, but he saw and painted images that answered to an instinctive personal need, like Cezanne’s, to anchor his contemporary images with qualities of work already in the museums. In other words, to anchor what was new around him with what remains always true in art, regardless of when it’s created. For both artists, this meant a reliance on geometrical structure, though I’ve always thought it’s far less obvious in Cezanne, despite the fact that his theories on this provided the seeds for Cubism. The architecture of the world around him gave Caillabotte a way to construct complex images with geometric unity. This was all instinctive, an imperative to stay away from the Impressionist haze in which objects melt into a pleasant miasma of light. (Kuspit says all of this from a different angle.) Yet this wasn’t so much a way of creating sociological commentary on modern life but his response to what is for an artist an almost physical need to create soundly structured pictures. If the sociological implications follow, for a critic improvising ideas around these images, fine. The images themselves arose from inarticulate imperatives. (Images that don’t arise that way hold little power.)

So what does Caillabotte actually convey? In his most famous painting, Paris Street, Rainy Day, he does everything Kuspit describes: it’s almost a diptych, with the painting on the right intimate and personal, the pedestrians walking to join the viewer, maybe for conversation. The painting on the left is a maze of looming and receding planes, the rising apartment walls uniformly styled, the same dull, repetitive shapes everywhere, like wallpaper. Yet on the left, paradoxically, the light invitingly melts across the cobbles of a drenched street. You can almost smell the ozone. The impersonal labyrinth of the city glows with light and the joy of that fresh air. Everything seems possible in that vast, open and glowing space. You want to lose yourself in it. The cozier imaginary “room” that contains the approaching walkers seems to become more and more intimate as you feel them coming toward you, and also more and more cramped. The canyons to the left pull your eye away into an indefinite distance while the cluster of individuals on the right feel like a bubble of companionship moving freely through the city. The lamp post running down the center of the painting hinges the diptych, and the two halves do feel almost like alternate visions of French urban life, one collective and the other personal, but they also fuse into one, with the gentleman’s top hat working like the hole in a phonograph record: everything circles around this eccentric axis formed by the individual who moves through the world to take it all in. Everything is unified, and the interlocked images give you a sense of elation and renewal, exactly the feeling of walking out onto fragrant wet pavement in the summer after a thunderstorm. You see it all as if you are hovering a foot off the ground, floating, a little high, both literally and figuratively. The painting seems to say there’s a regimented order everywhere here, but look at how much room there is to move.

So what does Caillabotte actually convey? In his most famous painting, Paris Street, Rainy Day, he does everything Kuspit describes: it’s almost a diptych, with the painting on the right intimate and personal, the pedestrians walking to join the viewer, maybe for conversation. The painting on the left is a maze of looming and receding planes, the rising apartment walls uniformly styled, the same dull, repetitive shapes everywhere, like wallpaper. Yet on the left, paradoxically, the light invitingly melts across the cobbles of a drenched street. You can almost smell the ozone. The impersonal labyrinth of the city glows with light and the joy of that fresh air. Everything seems possible in that vast, open and glowing space. You want to lose yourself in it. The cozier imaginary “room” that contains the approaching walkers seems to become more and more intimate as you feel them coming toward you, and also more and more cramped. The canyons to the left pull your eye away into an indefinite distance while the cluster of individuals on the right feel like a bubble of companionship moving freely through the city. The lamp post running down the center of the painting hinges the diptych, and the two halves do feel almost like alternate visions of French urban life, one collective and the other personal, but they also fuse into one, with the gentleman’s top hat working like the hole in a phonograph record: everything circles around this eccentric axis formed by the individual who moves through the world to take it all in. Everything is unified, and the interlocked images give you a sense of elation and renewal, exactly the feeling of walking out onto fragrant wet pavement in the summer after a thunderstorm. You see it all as if you are hovering a foot off the ground, floating, a little high, both literally and figuratively. The painting seems to say there’s a regimented order everywhere here, but look at how much room there is to move.

This is the track Kuspit is following. Yet, as with all art criticism, this is a way of talking around the actual work this painting, or any other painting, is doing. It’s a way of mastering the image with words, and words operate in a fragmented way a visual image is able to bypass completely. Most art criticism describes what a critic thinks about the painting, or about painting in general, and serves as a commentary that essentially circles the image, jabbering away, while the great painting long ago did its work, silently, requiring little or no intellectual clarification. Tom Wolfe, in The Painted Word, lamented how, as he saw it, art turned a corner toward words and ideas in the 20th century and away from the true work of a visual medium, which was exclusively visual. What, exactly, can be conveyed visually, but not through spoken language, remains essentially beyond the reach of language—and thought. When analytical thought addresses a visual medium, it avoids the truth that there essentially is no language to describe what’s at work in a painting. You can describe in some degree how it works, but not what it delivers. And painting which offers little grist for deconstruction—Impressionism for example—is then denigrated as work devoted to “sensation,” or “emotion,” or, of course, mere “impressions” and “appearances” implying that the real labor of art is much deeper, rising up from ideas, and social or political commitment, and so on, all in terms that offer a feast for the intellect. Art can effectively illustrate or embody ideas, but the ability to yoke visual images to intellectual content isn’t what makes painting unique among all the arts.

Kuspit, our greatest art critic alongside Danto, works brilliantly toward his conclusions about Caillabotte and they are accurate, if you study the paintings and are willing to pigeonhole an individual within his own “ism”: he was neither an inconsistent Impressionist nor an academic realist, but a “critical realist” someone who conveyed the socially repressive regime of Napoleon III, as well as the ways in which this dictator was actually making life better—at the price of conformity. Go along to get along, and everything will be fine. We’re led to think this is the guiding idea at the heart of this painter’s work, what makes him superior to mere Impressionism. As a way of deconstructing Caillabotte, his argument is airtight. All along, he is intellectualizing the work, so that it becomes grist for thought, ignoring the way in which pictures work subconsciously, directly, conveying far more than analytical thought can objectify. He certainly isn’t alone. It’s what nearly all art criticism, as a discipline, does. It’s what’s happening here, as I write these words. Behind all of this is a turning way from the power of painting to convey the essentially intangible isness of a human life’s passage through time, and those moments when time intersects with what’s eternal—something far more encompassing than any particular ideas the work of art can be intended to express. It does all this in a strictly visual way, without the need for reasoning. Visual art is not an intellectual activity; but to admit this leaves a critic with little to do. Along with most critics, Kuspit is quietly leading the reader to exactly the opposite conclusion and using Caillabotte to lure us down the path, implicitly denigrating Impressionism as a straw man, in contrast with Caillabotte’s sophistication.

He says that Caillabotte’s unique sense of perspective and pictorial structure elevates his work above Impressionism: Caillabotte creates an “intelligible” picture while the Impressionists weren’t intellectuals. My italics here:

His repeated use of perspective makes the point clearly: perspective is an intellectual device—a rational way of structuring and stabilizing space and reflectively constructing an intelligible picture—and the Impressionists slowly but surely eliminated it, perhaps unwittingly but inevitably undermined it, for “impressions” are not seen in perspective, nor do they exist in perspective, nor are they intellectual phenomena.

Caillabotte is not only being intellectualized here, he himself is now seen as an intellectual using paint to communicate his ideas about society. Not only that, he’s a postmodernist to boot: his perspective destabilizes everything so that “it may inhabit a place, as it were, but it is not bound to any place, for it relentlessly moves off the bridge into the streets in the background, and, implicitly, into the infinity beyond them.” There is no true perspective, no place to anchor oneself in an entirely alienating world . . . it is all relative.

All of this is grounded convincingly in what Kuspit has observed in the work–his argument is fully supported and sound. Given the terms of his argument, he’s absolutely right. And yet none of it addresses what seems most valuable and least expressible in the paintings themselves. That’s the rub.

Of all Caillabotte’s paintings, my favorite is entitled Snow Effect. Here the perspective is probably as elevated as he ever got it, an extreme version of what Kuspit describes: the viewer could be on a rooftop, several stories up, looking down at a residential neighborhood, floating slightly above it all. Or, as David Byrne put it, the viewer could be in the process of “rising up above the earth.” It appears everyone else is fast asleep in the heart of winter. It could be Christmas morning, but I’m guessing any old morning in December or January, a dark dawn, all the fires having gone out overnight—not a wisp of smoke rising from the chimneys and stove pipes. The rigorous, regulated patterns of the public streets he usually paints give way to a personable jumble of Second Empire architecture, mansard roofs and shallow dormers. A human scale has been restored to everything in view, all the housing seen from his upper window or balcony. A dark pipe rises up above a chimney in exactly the center of the canvas—like the small hand of a clock pointing toward twelve, and it anchors everything around it, like the lamp in Paris Street, Rainy Day, and here it likewise emphasizes the scene’s asymmetry. The streets zigzag through the homes seemingly in random patterns and everything huddles together, as if for warmth, no lights glowing yet in any windows, but a few people are probably stirring without having yet lit a stove. The artist looks out at a pleasingly disordered world, his familiar and beloved neighborhood, in which every building has its own character and personality, like its inhabitants, and so his block is dark, cold, forbidding and yet silently lovely. You want to go out with him and wander, if only to hear your own solitary, snow-muffled footsteps as you crunch aimlessly through the snow. And then you come home to find all those snowy roofs banking sunlight up through your windows onto your ceiling, a perfect light for finishing a painting. It’s a cold, dark winter day, but when you see it in this work, you feel utterly at home in the truth of the ordinary human experience it conveys—the great beauty of an imperfect world perfectly shown. You love your life a little more for having seen it.

August 17th, 2016 by dave dorsey

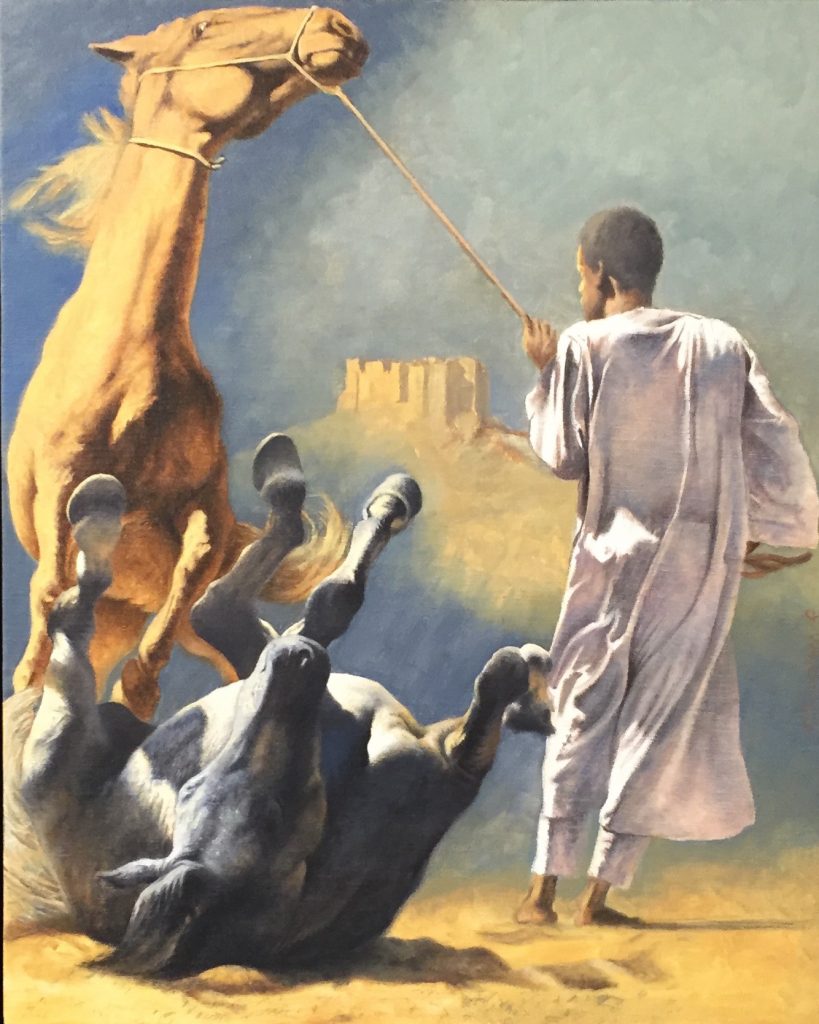

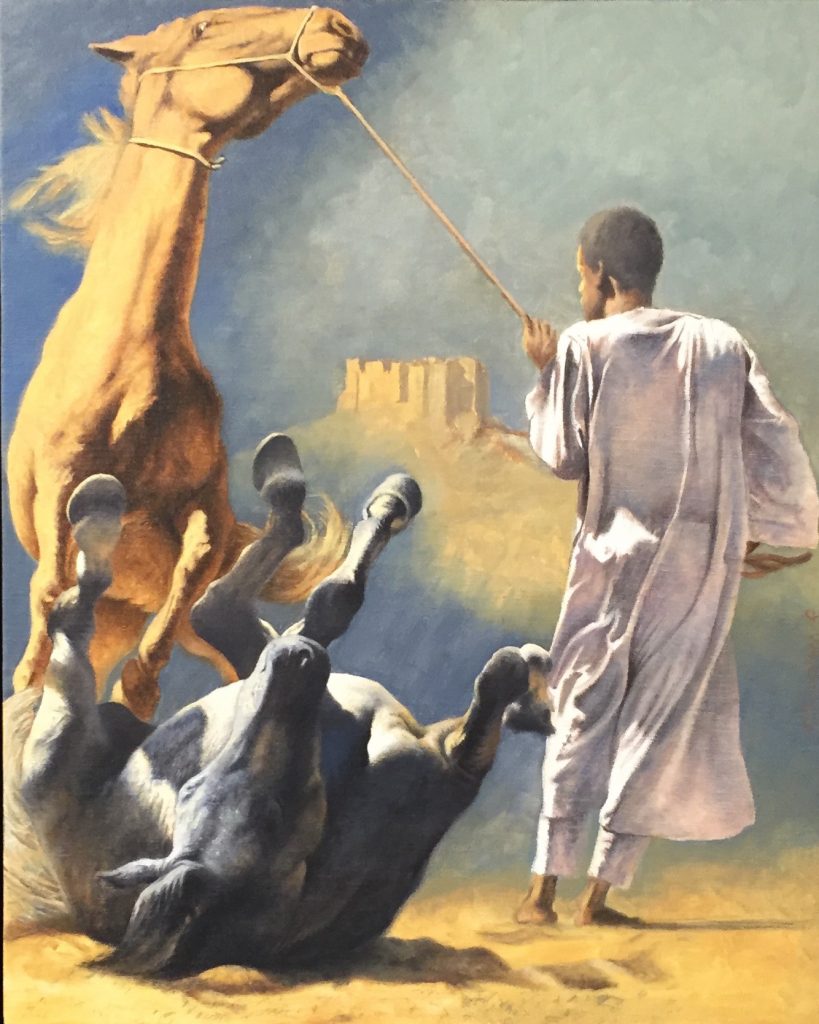

Study for Conversion of Saul, Tom Insalaco, oil on canvas

On Saturday, home for a week from Toronto, where I visited the Lawren Harris show at AGO, it struck me that I don’t need to drive three hours to see great art. If I make a point of getting out of my cave for a few hours, I can see dozens of great paintings, some astonishingly brilliant, with only a ten minute drive from my door. I remember when my parents moved to Pittsford, just outside Rochester, decades ago, and I was girding myself for my freshman year at the University of Rochester. Within weeks of our arrival, I visited our local museum, the Memorial Art Gallery, and was dumbfounded to realize that I lived only a few miles from a Rembrandt portrait. We’d moved here from the Northwest, and I’d been painting for three or four years at that point, and I’d never been to an art museum of any sort, and it was as if I’d stepped onto another planet, standing before that oil painting of a young man. Over the years–I moved away six years later and didn’t return to Rochester until another decade had passed–the collection at MAG has gotten deeper and richer. So on Saturday it was my middle stop between two other neighboring galleries, Makers Gallery and the home for my own work, Oxford Gallery, which has had an assortment of paintings and sculpture from gallery artists hanging throughout the summer. (The show ends in a couple weeks.) I got a glimpse of a full spectrum–a new, entrepreneurial space where local, exceptional emerging artists show their work, and then a museum that offers rare work from the most recent to centuries-old, and finally one of the area’s most established commercial galleries, still enduring with sporadic sales despite our endless economic stasis. It was gratifying, encouraging and energizing to see such great work in all of these distinctly different places.

At Maker’s, I got an early pre-reception glimpse–the show had just gone up–of work being given an encore from previous exhibits. It was all good, but I was especially impressed by some images on wood panels from Bill Stephens where he has taken paintings he’d put aside in the past and partially sanded them to reveal what amount to newly discovered and purely imaginary scenes. They evoke other worlds, mountains and seas from a crepuscular dream. They could be mythical landscapes viewed through isinglass. I’d seen Andrea Durfee’s landscapes at an earlier show there, but this time around I recognized more clearly how effective they are: geometrically vectorized scenes in which the lines define luxuriantly colored cells constructed into images that work as both representation and abstraction. To put it more directly: she can turn the human form into hills and hills into faceted gems.

Every time I visit MAG, I have the same feeling: a sense of startled gratitude for the intelligence behind its collection and the exhibits it pulls together, sometimes within severe constraints. When you walk into the exhibition space right now, you’ll find yourself spending half an hour in what would otherwise have been a foyer, but has been turned into an eclectic survey of portraiture. It offers an incredible range of work, from a portrait of John Ashbery by Elaine de Kooning to Kehinde Wiley to Sir Joshua Reynolds and a dazzling, effortlessly executed–did he ever make a false move?–oil from John Singer Sargent. What most impressed me about this show, aside from how the curators had leveraged the small, available space, was the way it worked for nearly anyone who spent time with it. Those with a deep knowledge of art would find gratifying surprises: a representational work from Elaine de Kooning, and not only that but an immediately recognizable likelness of a major American poet who happened to have been born here in Rochester. Yet a class of secondary students would be just as charmed by the work, and the carefully, accessibly worded descriptions of each painting. I’ll be posting examples of work I saw at MAG on Saturday, both from this show and from the permanent collection, all of which made me intensely grateful for having such easy access to such exhilarating work.

My final stop was also my longest, since whenever I visit Oxford, I end up having a cup of coffee and a two-hour conversation with Jim Hall on a dozen topics, in which I basically try to prompt him to amaze me with his knowledge of European and American history, Western art, philosophy, gardening, or politics. As we talked I kept focusing, as I’d done at both Makers and MAG, on work I’d seen before, but hadn’t fully recognized. I had a clear sightline to a small oil from Tom Insalaco, a preparatory study for his Conversion of Saul, a large painting indebted to Caravaggio that I’d seen in an earlier show. Somehow I’d overlooked this little study before, brightly lit, set in the desert, with two horses, one rearing up in protest and the other toppled to the ground, with a figure who looks both Bedouin and African. It’s a remarkable, dynamic image, a controlled exploration of how much can be done with a palette restricted to bluish/gray and gold, along with the stallion handler’s white thawb. In this little image, Tom has embedded multiple ironies. For one, there is no Saul. For another, as a whole, the image seems more a commentary on the Arab Spring than an exegesis of a Biblical parable. One horse has been toppled and another is rearing up, nearly out of control, and the ostensible handler is more bystander than active agent, exerting little control over what’s happening. In the distance, a structure that seems nearly swallowed up by a sandstorm. Insalaco’s work almost always has that fertile ambiguity, laden with multiple, sorrowful ironies about contemporary life, even when his subject is supposedly thousands of years old.

More to come from my visits on Saturday.

August 10th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Mountain Forms, Lawren Harris

In Toronto this past weekend, I had a chance to see the Lawren Harris retrospective, a show that brings the work home from its previous exhibition at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Curated by Steve Martin, the show does exactly what it set out to do: reveal the greatness of Harris’s achievement in the first two thirds of his career before he moved into a pure abstraction influenced by Kandinsky. The exhibition offered two visual feasts in one and gave me a more effective experience of Harris’s best work than any of the plodding documentaries about him available on line.

Harris became three different painters during the course of his career. In his first period, he was influenced by Post Impressionism, as well as Americans like Hopper and Burchfield, in his depiction of the rundown, industrial sections of Toronto called The Ward. In thickly-loaded and intensely colorful paint, he conveyed a kind of seasonal grace infused into what would otherwise have been squalid scenes of row houses and hazy factories. It’s tempting to rush through the rooms devoted to these paintings on the way to the paintings of the “North,” but Harris could have quit painting after doing these urban scenes and still be worthy of a retrospective. And yet the focus of the exhibit, his paintings of his imaginary “North” are even more powerful. He simplifies what he depicts, eliminating most detail and reshaping nature into geometric forms that convey energy and structure and light. The amazing thing is that they actually look natural, as if the planet had finally figured out how to get a mountain or an island exactly right. He somehow manages to capture the subtle play of actual daylight on almost completely imaginary forms. The effect is that you’re invited into a visually coherent world that feels both eternal and otherworldly and yet recognizable and arising out of some inner necessity that gave Harris his own idiosyncratic measure for accuracy in what he was doing—when he was only elaborating on sketches done from direct observation.

As it did for Burchfield, the idea of the “North” represents a spiritual state for Harris. In simplified representations of mountains, glaciers, lakes and sky, Harris found a way to balance abstraction with representation in a personal way. You can feel, in the paint itself, how much care went into every square inch of the canvas–Georgia O’Keefe comes to mind repeatedly, both in the simplified and abstract rendering of nature, but also in the deliberate care given to the quality of the paint on the surface. It’s hard to grasp how resonant and serene these images are in reproductions. These paintings are both absolutely still, completely at rest, and yet they radiate an intense, vital energy and clarity of mind.

August 1st, 2016 by dave dorsey

Habakkuk, the prophet, by Donatello

I happened upon an innocuously titled entry, “Taste and Aesthetics”, in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy last night, and it brought to mind a brief section in Heidegger’s lectures on Nietzsche, where the German philosopher celebrates Kant’s theories of beauty—particularly the notion that a human being’s reaction to beauty is “disinterested.” Heidegger praises Kant for this insight that maintains the effect of a work of art has nothing to do with desire—the impulses or motivations an individual harbors, at any level. Art serves no purpose, no end, other than to be what it is. Like human life, it is not a tool, not meant to achieve anything. It’s an end in itself–and thus can convey an awareness of the whole of life, or, for Heidegger, Being. Here is how the Stanford entry summarizes it:

For Kant the pleasure involved in a judgment of taste is disinterested because such a judgment does not issue in a motive to do anything in particular. For this reason Kant refers to the judgment of taste as contemplative rather than practical (Kant 1790, 95). But if the judgment of taste is not practical, then the attitude we bear toward its object is presumably also not practical: when we judge an object aesthetically we are unconcerned with whether and how it may further our practical aims. Hence it is natural to speak of our attitude toward the object as disinterested.

This sounds like blasphemy when you consider what is routinely celebrated in the art world now–how much art is meant to have a political or social “message.” I was puzzled at first why Heidegger dwells at some length on this issue, and especially the fact that he was siding with Kant, when Heidegger’s fundamental concern is ontological: “the question of Being.” Yet as I spent some time with his asides on Kant I realized that he recognized how Kant was, in a way, putting art beyond the reach of his own rationalism. In a like-minded way, the thrust of Heidegger’s effort was to recognize the limitations of Western rationalism and Western philosophy in general.

(Heidegger’s view is that Western philosophy has been unintentionally nihilistic since Plato, and that Nietzsche’s thought represents nihilism in full, decadent bloom. Nietzsche believed he was overcoming nihilism with his notion of the ubermensch and the will to power, but for Heidegger these notions represented the pinnacle of nihilism, its ultimate form–and the dead end of Western metaphysics. For Nietzsche and for Heidegger, art was an affirmation of life in opposition to nihilism, but the two philosophers had dramatically different views of how this works. Nietzsche was a prophet, not of fascism, but of where we have arrived as human beings on this planet. The human race has collectively become his ubermensch, in its march toward the mastery and manipulation of nature through science and technology. By contrast, Heidegger’s lifelong effort was to warn against the dangers of Western hyper-rationalism, in which the natural world and human beings themselves become raw material to be shaped by the will to power inherent in science and technology. Anyone who doesn’t recognize how Nietzsche’s predictions have come true in this way is living in denial.)

In his philosophy, Heidegger was reverting to the contemplative puzzlement of the pre-Socratic thinkers, like Heraclitus and Parmenides, who asked foundational, unanswerable questions without moving far beyond those questions. This Stanford entry echoes Heidegger’s concerns about the limitations of Western rationalism:

Rationalism about beauty is the view that judgments of beauty are judgments of reason, i.e., that we judge things to be beautiful by reasoning it out, where reasoning it out typically involves inferring from principles or applying concepts. At the beginning of the 18th century, rationalism about beauty had achieved dominance (through the work of) a group of literary theorists who aimed to bring to literary criticism the mathematical rigor that Descartes had brought to physics.

It was against this, and against more moderate forms of rationalism about beauty, that mainly British philosophers working mainly within an empiricist framework began to develop theories of taste. The fundamental idea behind any such theory—which we may call the immediacy thesis—is that judgments of beauty are not (or at least not primarily) mediated by inferences from principles or applications of concepts, but rather have all the immediacy of straightforwardly sensory judgments.

Behind this lies an unasked question about what visual art is uniquely able to do— MORE

So what does Caillabotte actually convey? In his most famous painting, Paris Street, Rainy Day, he does everything Kuspit describes: it’s almost a diptych, with the painting on the right intimate and personal, the pedestrians walking to join the viewer, maybe for conversation. The painting on the left is a maze of looming and receding planes, the rising apartment walls uniformly styled, the same dull, repetitive shapes everywhere, like wallpaper. Yet on the left, paradoxically, the light invitingly melts across the cobbles of a drenched street. You can almost smell the ozone. The impersonal labyrinth of the city glows with light and the joy of that fresh air. Everything seems possible in that vast, open and glowing space. You want to lose yourself in it. The cozier imaginary “room” that contains the approaching walkers seems to become more and more intimate as you feel them coming toward you, and also more and more cramped. The canyons to the left pull your eye away into an indefinite distance while the cluster of individuals on the right feel like a bubble of companionship moving freely through the city. The lamp post running down the center of the painting hinges the diptych, and the two halves do feel almost like alternate visions of French urban life, one collective and the other personal, but they also fuse into one, with the gentleman’s top hat working like the hole in a phonograph record: everything circles around this eccentric axis formed by the individual who moves through the world to take it all in. Everything is unified, and the interlocked images give you a sense of elation and renewal, exactly the feeling of walking out onto fragrant wet pavement in the summer after a thunderstorm. You see it all as if you are hovering a foot off the ground, floating, a little high, both literally and figuratively. The painting seems to say there’s a regimented order everywhere here, but look at how much room there is to move.

So what does Caillabotte actually convey? In his most famous painting, Paris Street, Rainy Day, he does everything Kuspit describes: it’s almost a diptych, with the painting on the right intimate and personal, the pedestrians walking to join the viewer, maybe for conversation. The painting on the left is a maze of looming and receding planes, the rising apartment walls uniformly styled, the same dull, repetitive shapes everywhere, like wallpaper. Yet on the left, paradoxically, the light invitingly melts across the cobbles of a drenched street. You can almost smell the ozone. The impersonal labyrinth of the city glows with light and the joy of that fresh air. Everything seems possible in that vast, open and glowing space. You want to lose yourself in it. The cozier imaginary “room” that contains the approaching walkers seems to become more and more intimate as you feel them coming toward you, and also more and more cramped. The canyons to the left pull your eye away into an indefinite distance while the cluster of individuals on the right feel like a bubble of companionship moving freely through the city. The lamp post running down the center of the painting hinges the diptych, and the two halves do feel almost like alternate visions of French urban life, one collective and the other personal, but they also fuse into one, with the gentleman’s top hat working like the hole in a phonograph record: everything circles around this eccentric axis formed by the individual who moves through the world to take it all in. Everything is unified, and the interlocked images give you a sense of elation and renewal, exactly the feeling of walking out onto fragrant wet pavement in the summer after a thunderstorm. You see it all as if you are hovering a foot off the ground, floating, a little high, both literally and figuratively. The painting seems to say there’s a regimented order everywhere here, but look at how much room there is to move.