Archive for February, 2017

February 27th, 2017 by dave dorsey

This is a ceramic representation of the earth as originally imagined in an Iroquois creation myth of the “world on a turtle’s back.” In the original myth the world rests on the back of a giant turtle, the American Indian equivalent of the Medieval notion of a firmament. In Barron Naegel’s reworking of the myth, the turtle and the planet are fused into one orb, the shell forming the bedrock below the life on the surface. Which happens to be, more or less, close to the way we view the planet ourselves. In Naegel’s small solo show at Keuka College you can see his latest figure drawings and his reinterpretation of the Iroquois myth in raku pottery. The drawings are masterful and traditional, studies from models at Steve Carpenter’s studio, and bring to mind the Renaissance and the Grand Central Atelier, though in them he’s trying to find a middle ground between representation and abstraction. One in particular, a cluster of figures woven together into a braid of limbs, brought to mind Nude Descending a Staircase. His raku planet is the show’s stand-out, and it was literally a trial by fire, a spontaneous process of discovering color experimentally through chemistry and heat–turning him into a bit of an alchemist. Here is how Barron described the process of getting the orb to its finished state through “re-oxidation”:

This is a ceramic representation of the earth as originally imagined in an Iroquois creation myth of the “world on a turtle’s back.” In the original myth the world rests on the back of a giant turtle, the American Indian equivalent of the Medieval notion of a firmament. In Barron Naegel’s reworking of the myth, the turtle and the planet are fused into one orb, the shell forming the bedrock below the life on the surface. Which happens to be, more or less, close to the way we view the planet ourselves. In Naegel’s small solo show at Keuka College you can see his latest figure drawings and his reinterpretation of the Iroquois myth in raku pottery. The drawings are masterful and traditional, studies from models at Steve Carpenter’s studio, and bring to mind the Renaissance and the Grand Central Atelier, though in them he’s trying to find a middle ground between representation and abstraction. One in particular, a cluster of figures woven together into a braid of limbs, brought to mind Nude Descending a Staircase. His raku planet is the show’s stand-out, and it was literally a trial by fire, a spontaneous process of discovering color experimentally through chemistry and heat–turning him into a bit of an alchemist. Here is how Barron described the process of getting the orb to its finished state through “re-oxidation”:

Raku can be a scary process, to say the least. I usually use tongs to remove the work. However I had to use an alternative approach, which in this case was to just grab it. I had all this  apprehension about heat, so I used firemen gloves blanketed with phone books completely saturated in water. First of all, I don’t have a Raku kiln which makes this process a lot, lot easier. So I basically have to lean over into the heat. The object itself is molten and it’s about as heavy as a bowling ball, but one with oil all over it, because of the molten glass. A slippery bowling ball at 1900 degrees! The process of Raku is based on reduction: it’s all chemistry. I’m stripping away the oxygen from the

apprehension about heat, so I used firemen gloves blanketed with phone books completely saturated in water. First of all, I don’t have a Raku kiln which makes this process a lot, lot easier. So I basically have to lean over into the heat. The object itself is molten and it’s about as heavy as a bowling ball, but one with oil all over it, because of the molten glass. A slippery bowling ball at 1900 degrees! The process of Raku is based on reduction: it’s all chemistry. I’m stripping away the oxygen from the glaze and introducing more carbon, which changes the metal colorants. How did I get it to where I wanted it? The blue and green you see on the surface are the result of re-oxidation. The first time I fired it, it came out red, looking more like Mars! I reheated it to about 800 degrees a baseline temperature, and then with a welding torch reworked areas to get certain colors. I had to try three times to get it to work out.

glaze and introducing more carbon, which changes the metal colorants. How did I get it to where I wanted it? The blue and green you see on the surface are the result of re-oxidation. The first time I fired it, it came out red, looking more like Mars! I reheated it to about 800 degrees a baseline temperature, and then with a welding torch reworked areas to get certain colors. I had to try three times to get it to work out.

Using firemen’s gloves and wet phone books as a buffer between the gloves and the pottery, which would have stuck to the molten glass, he was able to retrieve his globe from the fire. It’s an unpretentious technique also used at the Corning Glass Works for handling molten forms only an hour’s drive away. It struck me that with his ceramic planet, Naegel was replacing oxygen with carbon in the surface to get the color he wanted, much as we’re doing (sort of) to the actual planet, but in his case, it had exactly the desired effect: turning a dull red sphere into this emerald world.

February 20th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Ryan Adams, a while ago

You get the sense from some creative work, Proust’s maybe more than anyone who ever lived, that the author of the work considered everything in some sense magically interesting or valuable–and this is where language offers no adjective for what a work of art actually conveys, the isness of things. It isn’t that what’s being represented is valuable, or marvelous, or (pick any other available adjective.) It’s something else. What you sense from looking at a Van Gogh or reading Swann’s Way is how the individual who created the work had what the fellow I’m going to quote below called a total appreciation for life just as it is-with nothing left out, including the crime and the evil and the horrible suffering and injustice. Bruegel has this quality–there’s nothing that isn’t worthy of being painted, and when he paints it, it’s suddenly (again, try to imagine that non-existent adjective or noun). There’s no word for what’s going on in that transformation or disclosure that happens in art. Language has no verb for the work being done by the painting or the novel. Celebrate, affirm, savor, appreciate, cherish–sorry, no. Below are seemingly extemporaneous observations that attempt to express (bumping intentionally up against the limits of language and showing how words fail to capture what’s going on) the urge to create something that will condense life itself into some created thing, or (what amounts to the same thing) alchemically make something inanimate appear to come alive. In a way, the urge to create is something like the will to be so aware of everything that you yourself are fully alive. These are remarks from the singer Ryan Adams, talking with Bob Boilen in the most recent episode of NPR’s All Songs Considered. It gets close to showing how impossible it is to say what’s really happening in great creative work, in any medium:

You manifest a meaning from a thing to yourself, in whatever format, a painting, a poem, a song, an article, or a novel or a note to a friend or a drunken text or email or spray painting on brick walls or inappropriately decaling your car. You conjure this feeling. There’s this thing inside of human beings, this total appreciation of being alive. It’s so profoundly in our gut. Even all of these people who would seemingly be horrible people, somewhere in there there’s this longing, this reaching up, and in the right way if it’s channeled, there’s some kind of a notion in them of “I have to document this thing that I saw” that becomes these songs, or these poems. We’re all in the high school of life and waiting for the teacher to turn around so we can take that pen we’ve been chewing on long enough that it’s got a sharp enough end that you could scratch your initials into that ventilator in gray/blue paint over by the window. It’s the same thing as those beautiful drawings in caves, where you see pictures of horses and wild game they were hunting. That person that day was either thinking of how beautiful those animals were or how it felt to be out there with them that day.

February 17th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Sweet Kate, In for Repairs, Ray Hassard, oil on canvas

I came away from the current show at Oxford Gallery craving more excellent oils from Ray Hassard. His pastels are masterful and the latest work he’s been doing in Florida may be better than anything he’s done in the past: the way he captures the light so that it gives a sense of depth and even immense volume to the space in these small landscapes is remarkable. Yet, maybe because I’m an oil painter, my favorites are the oils in the current Oxford show. Like a number of other Oxford artists—Chris Baker and Matt Klos—he’s fascinated by the most commonplace scenes. Beyond the immediate pleasure offered by the color and the play of light and shadow, he conveys a sense of completion and harmony in scenes that invites you to look again, in a fresh way, as if for the first time at scenes you otherwise might not even notice. Hassard picks the least auspicious subjects: a leftover holiday decoration on New Year’s Day, a crossing guard brandishing a stop sign, or someone nearly lost in shadow cleaning and repairing an old boat in storage. My favorite painting of Hassard’s was in a previous show at Oxford, a small image of a parked pickup truck, a view one could enjoy of thousands of trucks parked in small towns and villages anywhere in dozens of states—and you would never give any of them a second look if you passed them on the way to somewhere else. The light, the color, and the abbreviated rendering with assured brushwork—he could have done the painting in a single sitting, en plein air—concentrate energy and a sense of ease in Hassard’s execution. Bill Santelli and Bill Stephens joined me at Oxford to see the new work and Santelli pointed out how Hassard again and again composes an image, like Diebenkorn, so that smaller areas of comparatively intense activity are clustered close to a top edge, with a more uniform expanse of color beneath it—a field, a floor—creating a tension between the complexity of form against an open void below it. Hassard’s real subject is the unity and uniformity of the light, rather than anything it reveals in particular. My favorite in this show is Sweet Kate, In For Repairs, his view of an old boat maybe being readied for another launch. It’s actually one of his least colorful, a field of neutral tones with a few small notes of muted orange, blue, green and a tiny stripe of red. In the foreground: a trash barrel with a loose load of scrap jutting out in all directions like a month-old bouquet, and a narrow, tall pylon. All the activity he depicts, the subject of the work, is just visible, pushed to the background, half-hidden in shadow. The worker, up on a ladder, is barely indicated, perfectly done, with a few patches of color, tucked away, almost out of view, like an Easter egg. The light is modulated gently throughout the entire scene, and even the higher reaches of the repair shop are dark but still dimly illuminated, with the darkest shadow reserved for small pockets of space under the boat. You feel the day, the season, a world in which the boat repair is neither more nor less interesting than the trash in the barrel—it’s all good and essential to the whole.

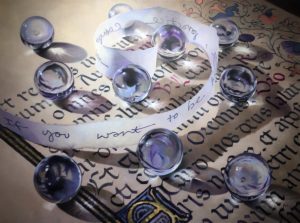

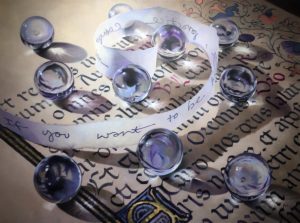

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.

February 12th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Bill Santelli, Untitled

Work in progress from Bill Santelli, for the upcoming Doppleganger group show at Oxford Gallery. I’m half done with my offering for the show, and the undone half is making me nervous. Maybe that’s fitting, given the theme.

February 10th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Piero della Francesca, Madonna and Child with Saints, Brera

The hardest task in life is to know yourself. In his essay on Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection, which Huxley called the greatest picture in the world, he makes this astute observation, but he saves his greatest wisdom until the end. The last sentence should be tacked to the wall of every painter’s studio:

“Is Fra Angelico a better artist than Rubens? Such questions, you insist, are meaningless. It is all a matter of personal taste. And up to a point this is true. But there does exist, none the less, an absolute standard of artistic merit. And it is a standard which is in the last resort a moral one. Whether a work of art is good or bad depends entirely on the quality of the character which expresses itself in the work. Not that all virtuous men are good artists, nor all artists conventionally virtuous. Longfellow was a bad poet, while Beethoven’s dealings with his publishers were frankly dishonorable. But one can be dishonorable towards one’s publishers and yet preserve the kind of virtue that is necessary to a good artist. That virtue is the virtue of integrity, of honesty towards oneself. Bad art is of two sorts: that which is merely dull, stupid and incompetent, the negatively bad; and the positively bad, which is a lie and a sham. Very often the lie is so well told that almost every one is taken in by it–for a time. In the end, however, lies are always found out. Fashion changes, the public learns to look with a different focus and, where a little while ago it saw an admirable work which actually moved the emotions, it now sees a sham. In the history of the arts we find innumerable shams of this kind, once taken as genuine, now seen to be false. The very names of most of them are now forgotten. Still, a dim rumor that Ossian once was read, that Bulwer was thought a great novelist and ‘Festus’ Bailey a mighty poet still faintly reverberates. Their counterparts are busily earning praise and money at the present day. I often wonder if I am one of them. It is impossible to know. For one can be an artistic swindler without meaning to cheat and in the teeth of the most ardent desire to be honest.”

–Aldous Huxley, “The Best Picture”, 1925, from The Piero Della Francesca Trail, John Pope-Hennessy, 1991

This is a ceramic representation of the earth as originally imagined in an Iroquois creation myth of the “world on a turtle’s back.” In the original myth the world rests on the back of a giant turtle, the American Indian equivalent of the Medieval notion of a firmament. In Barron Naegel’s reworking of the myth, the turtle and the planet are fused into one orb, the shell forming the bedrock below the life on the surface. Which happens to be, more or less, close to the way we view the planet ourselves. In Naegel’s small solo show at Keuka College you can see his latest figure drawings and his reinterpretation of the Iroquois myth in raku pottery. The drawings are masterful and traditional, studies from models at Steve Carpenter’s studio, and bring to mind the Renaissance and the Grand Central Atelier, though in them he’s trying to find a middle ground between representation and abstraction. One in particular, a cluster of figures woven together into a braid of limbs, brought to mind Nude Descending a Staircase. His raku planet is the show’s stand-out, and it was literally a trial by fire, a spontaneous process of discovering color experimentally through chemistry and heat–turning him into a bit of an alchemist. Here is how Barron described the process of getting the orb to its finished state through “re-oxidation”:

This is a ceramic representation of the earth as originally imagined in an Iroquois creation myth of the “world on a turtle’s back.” In the original myth the world rests on the back of a giant turtle, the American Indian equivalent of the Medieval notion of a firmament. In Barron Naegel’s reworking of the myth, the turtle and the planet are fused into one orb, the shell forming the bedrock below the life on the surface. Which happens to be, more or less, close to the way we view the planet ourselves. In Naegel’s small solo show at Keuka College you can see his latest figure drawings and his reinterpretation of the Iroquois myth in raku pottery. The drawings are masterful and traditional, studies from models at Steve Carpenter’s studio, and bring to mind the Renaissance and the Grand Central Atelier, though in them he’s trying to find a middle ground between representation and abstraction. One in particular, a cluster of figures woven together into a braid of limbs, brought to mind Nude Descending a Staircase. His raku planet is the show’s stand-out, and it was literally a trial by fire, a spontaneous process of discovering color experimentally through chemistry and heat–turning him into a bit of an alchemist. Here is how Barron described the process of getting the orb to its finished state through “re-oxidation”: apprehension about heat, so I used firemen gloves blanketed with phone books completely saturated in water. First of all, I don’t have a Raku kiln which makes this process a lot, lot easier. So I basically have to lean over into the heat. The object itself is molten and it’s about as heavy as a bowling ball, but one with oil all over it, because of the molten glass. A slippery bowling ball at 1900 degrees! The process of Raku is based on reduction: it’s all chemistry. I’m stripping away the oxygen from the

apprehension about heat, so I used firemen gloves blanketed with phone books completely saturated in water. First of all, I don’t have a Raku kiln which makes this process a lot, lot easier. So I basically have to lean over into the heat. The object itself is molten and it’s about as heavy as a bowling ball, but one with oil all over it, because of the molten glass. A slippery bowling ball at 1900 degrees! The process of Raku is based on reduction: it’s all chemistry. I’m stripping away the oxygen from the glaze and introducing more carbon, which changes the metal colorants. How did I get it to where I wanted it? The blue and green you see on the surface are the result of re-oxidation. The first time I fired it, it came out red, looking more like Mars! I reheated it to about 800 degrees a baseline temperature, and then with a welding torch reworked areas to get certain colors. I had to try three times to get it to work out.

glaze and introducing more carbon, which changes the metal colorants. How did I get it to where I wanted it? The blue and green you see on the surface are the result of re-oxidation. The first time I fired it, it came out red, looking more like Mars! I reheated it to about 800 degrees a baseline temperature, and then with a welding torch reworked areas to get certain colors. I had to try three times to get it to work out.

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.